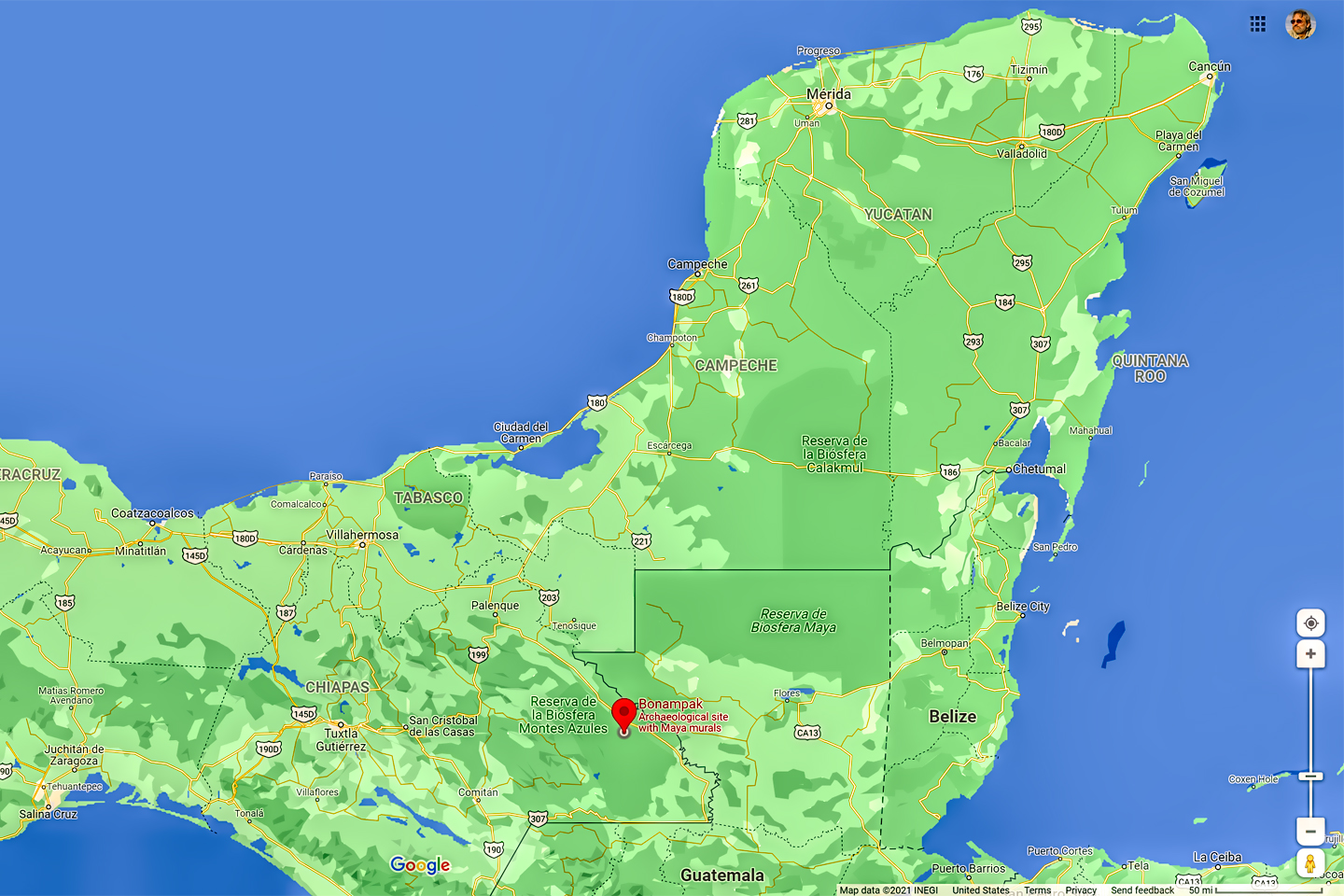

DOWN BY THE GUATEMALAN BORDER,

…in a remote corner of the Mexican state of Chiapas, there’s a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

The ancient, long abandoned city, really more of a large town, boasts an acropolis, topped by a couple of smallish third rate pyramids, crowned, in their turn, by some tiny fourth rate temples:

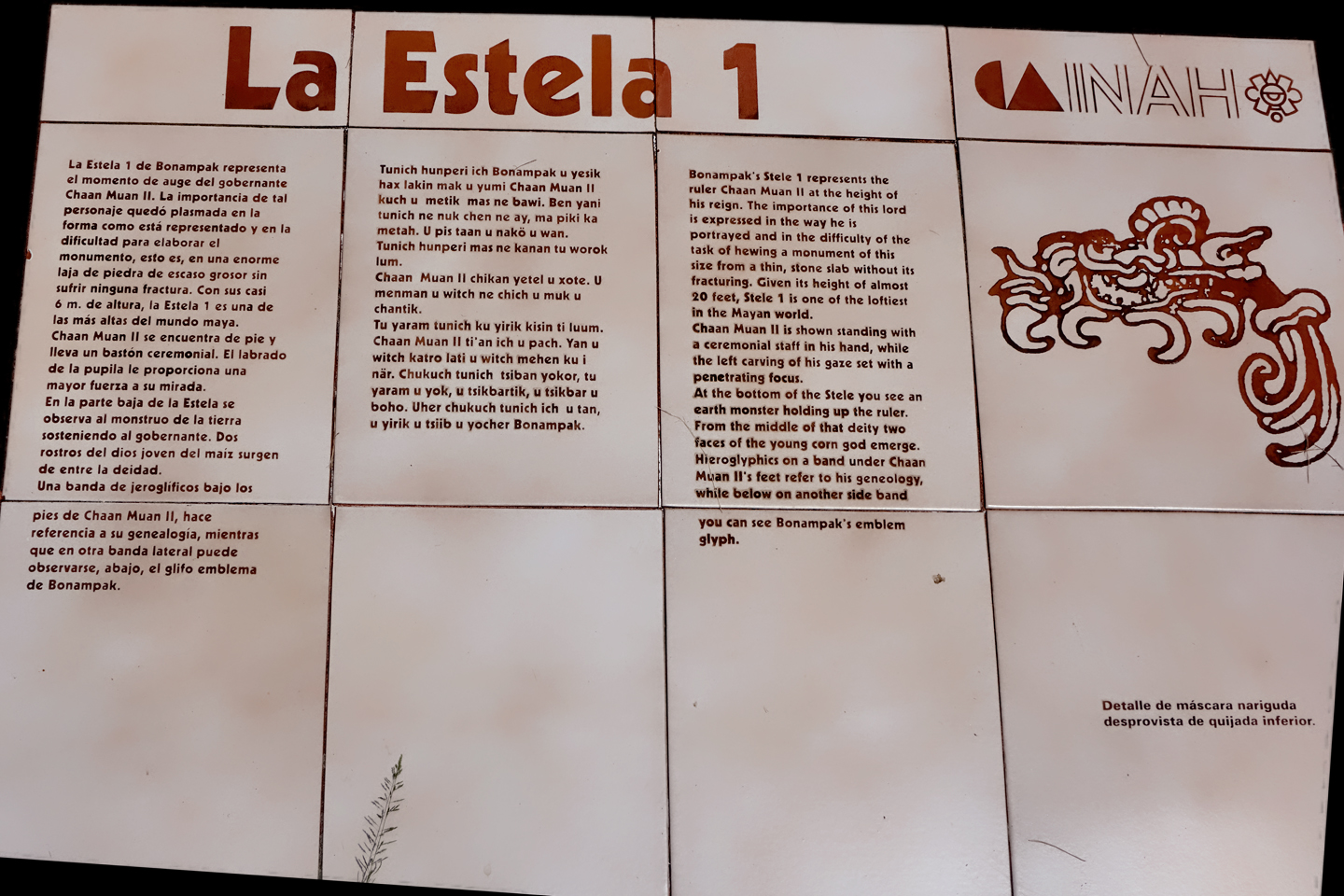

They’ve resurrected an assortment of stelae, the large, elaborately carved standing stones created by Maya sculptors to commemorate important events and encounters. (Click images to expand them to full screen.)

The stelae are quite nice, but none of the rest of it is particularly impressive, or particularly well preserved. Bonampak was at its peak in the late classic period, roughly, between 580 AD and 800 AD, but even then it was little more than a minor satellite of a much larger Mayan city known as Yaxchilan, 30 km to the north. Yaxchilan was their ally in war, and their patron in peace, their noble houses united by arranged marriages–but there was never any real question about who was in charge. The difference in status is still readily apparent. Compared to Bonampak, Yaxchilan actually is quite impressive, with massive, classically built pyramids in a uniquely dramatic jungle setting, right on the banks of the Usumacinta river. (Even today, the only way to get to the site is by boat). Yaxchilan is not only bigger, and finer, it was far more powerful, and infinitely more important historically.

Sign in Spanish, Mayan, and English describing Stela 1. At nearly 20 feet in height, this is one of the tallest in the Mayan world.

Ironically, with the passage of centuries, their positions have reversed. Of the two Mayan cities, Bonampak is much better known to the world at large, and its importance to Maya scholars is immeasurable. Needless to say, all of that is in spite of, certainly not because of those raggedy third-rate pyramids.

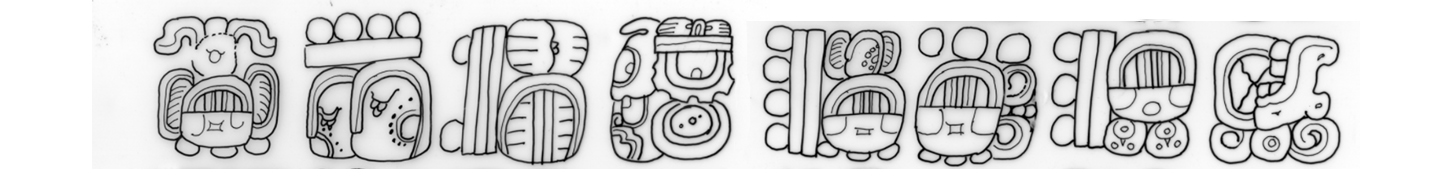

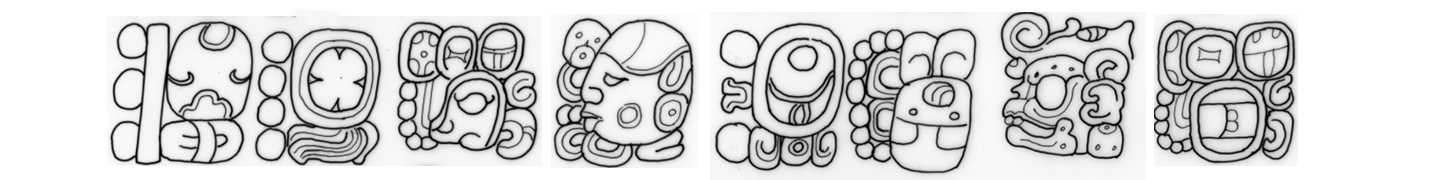

The Maya were extraordinary artists, and they worked in a wide variety of mediums. They were stone carvers, jewelry makers, potters, weavers, and painters, famous for their colorful murals. The stone carving is pretty obvious–palaces, temples, intricate facades, bas reliefs, statues and figurines fashioned from limestone and stucco, from granite, from jade and other semi-precious stone. The buildings, the statues, the stelae that commemorate historical events–those things are everywhere in the former domain of the Maya, hundreds of sites, many of them yet to be excavated. Most of the jewelry that has survived has been found in royal burials, and graces the prized collections of museums all around the world. The pottery–same deal. Much of what is still intact was recovered from burials, and the elaborate scenes painted on many of these funerary offerings provide us with some of our best insights into the religion, the customs, and the culture of the ancient Maya. The skill, and the craftsmanship, is unsurpassed.

The textiles, tapestries, and feather-work, all that elaborate regalia depicted in their bas reliefs and their polychrome pottery, that stuff has not fared so well over the centuries, certainly not in the damp climate of Central America. There are modern examples in museum collections, textiles created by the descendents of the ancient Maya, using traditional patterns and techniques, but all the original examples have long since rotted away or crumbled to dust. As have the paintings, unfortunately, particularly the elaborate murals that graced the interior walls of many palaces and temples. Those were likewise ravaged by exposure to the tropical climate–faded, flaked off, and crumbled to dust, leaving nothing but the occasional faint trace, or outline, with but a few rare exceptions. Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: that small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

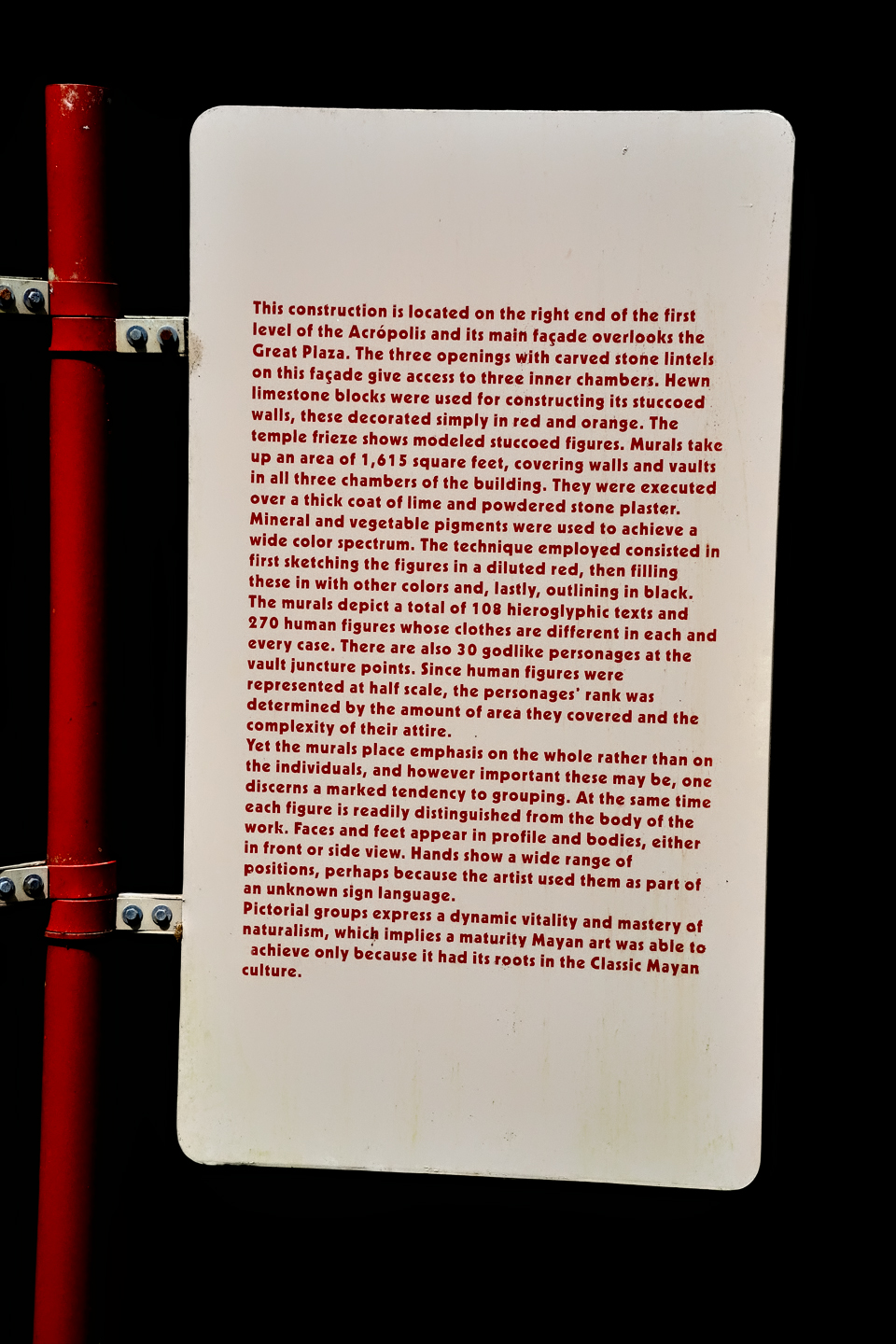

One of those fourth-rate temples that I mentioned is officially known as “Structure 1.” It’s a smallish building, fifty feet by twelve feet, divided into three small rooms. There are no windows, but each small room has its own door to the outside:

Temple of the Paintings

A corrugated sheet-metal roof was erected to protect the structure from the rain, and lockable doors were affixed, to protect the rooms from vandals after hours. On the inside, each of those rooms is a breathtaking window into history. The interior walls are covered from floor to ceiling with elaborate paintings that actually HAVE survived, larger, grander, and in better condition than any Mayan paintings found anywhere else, ever. The site was abandoned shortly after the murals were created, around 800 AD. Through a quirk of fate, good fortune, or random circumstance, the interior space had just enough protection from the elements to preserve the paintings in remarkably good condition.

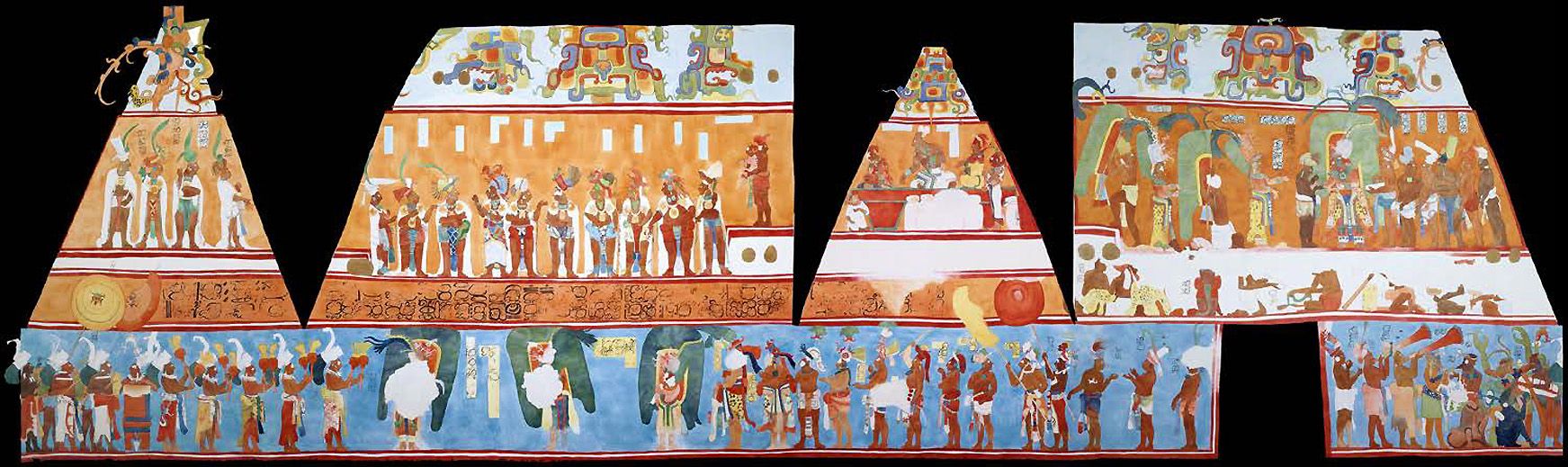

Each of the three rooms is different, but taken together, they provide a brilliant picture of the pomp and grandeur, as well as the monstrous cruelty of the Maya in the classic era, when Bonampak was a thriving metropolis.

The picture below is a rather famous detail from room 2, a battle scene, in which the Lord of Bonampak grasps a struggling prisoner by the hair. The man knows the fate that awaits him, and you can almost sense the fear in his expression.

There are conflicting stories about the discovery of the site. Fact is, it was never really lost–the local Lacondon Maya were still using it for religious purposes, and had always done so, until one of them showed the ruins to a young American named Charles Frey, in 1946. Some say that the first outsider to visit was actually a photographer/explorer named Giles Healey, but regardless of which of those two was first to visit the site, it was Healey’s photographs that first introduced the murals of Bonampak to the rest of the world.

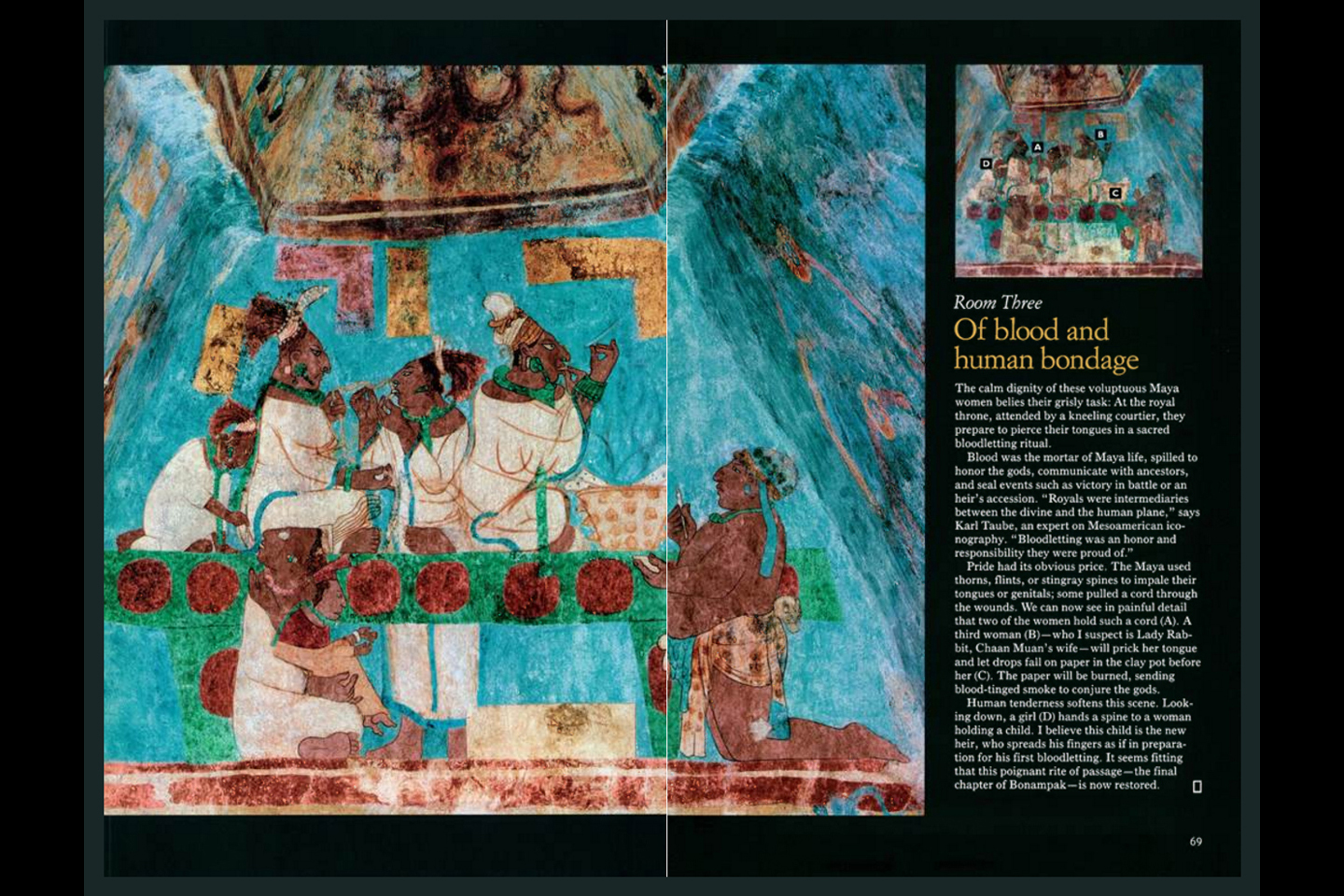

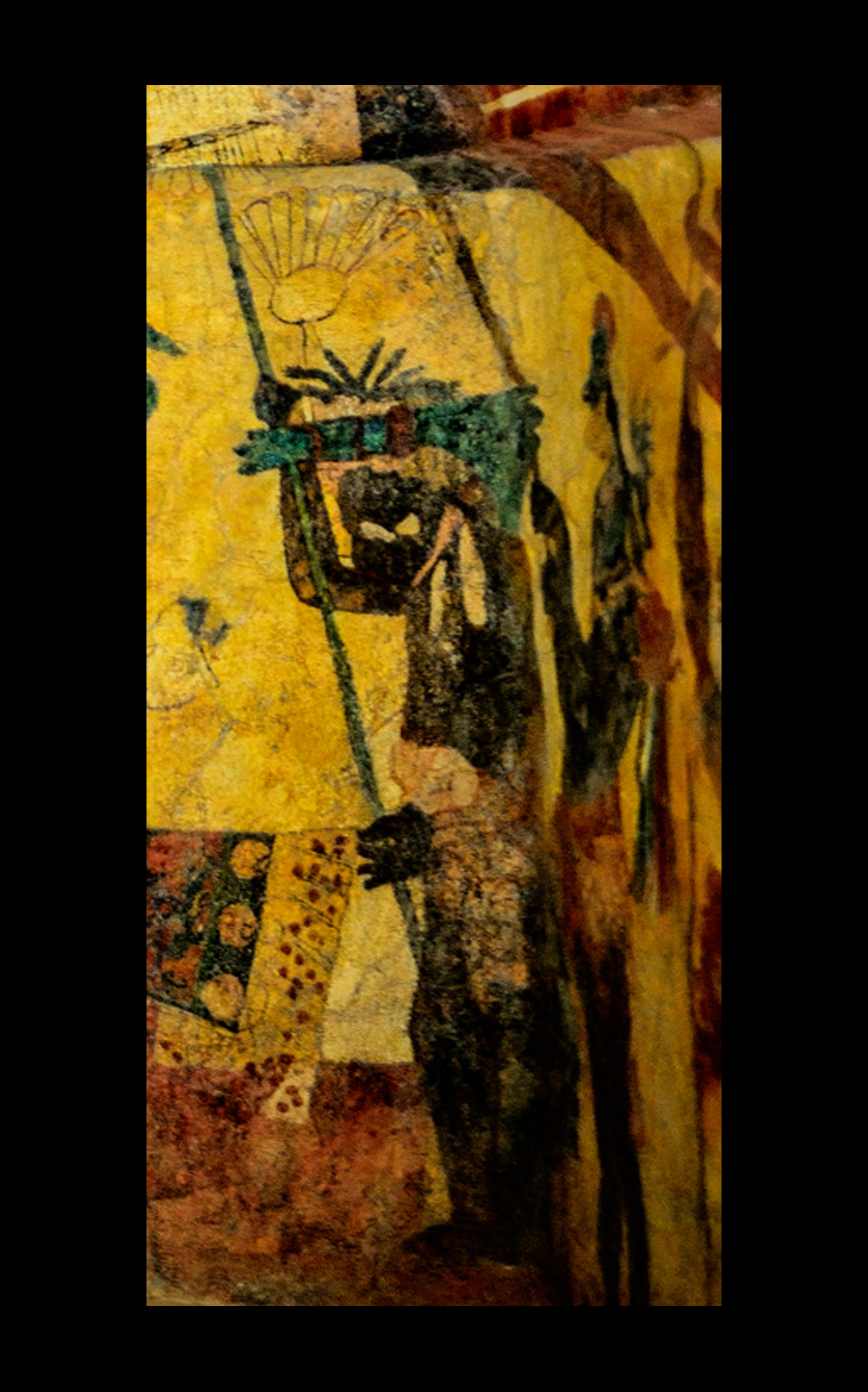

The murals have been extensively studied, and they provide a fascinating glimpse into the life of the court during the period when they were created. Each of the three rooms depicts a different scene, including celebrations and musicians, as well as battles, torture, and human sacrifice. Maya Lords wear severed human heads as necklace ornaments, captives are bound and mutilated, a group of noblewomen partake in a ritual that requires them to pierce their tongues with thorns, in a gruesome bloodletting ceremony. Before the discovery of these murals, it was popularly believed that the ancient Maya were peaceful mystics. The scenes depicted at Bonampak permanently debunked that notion.

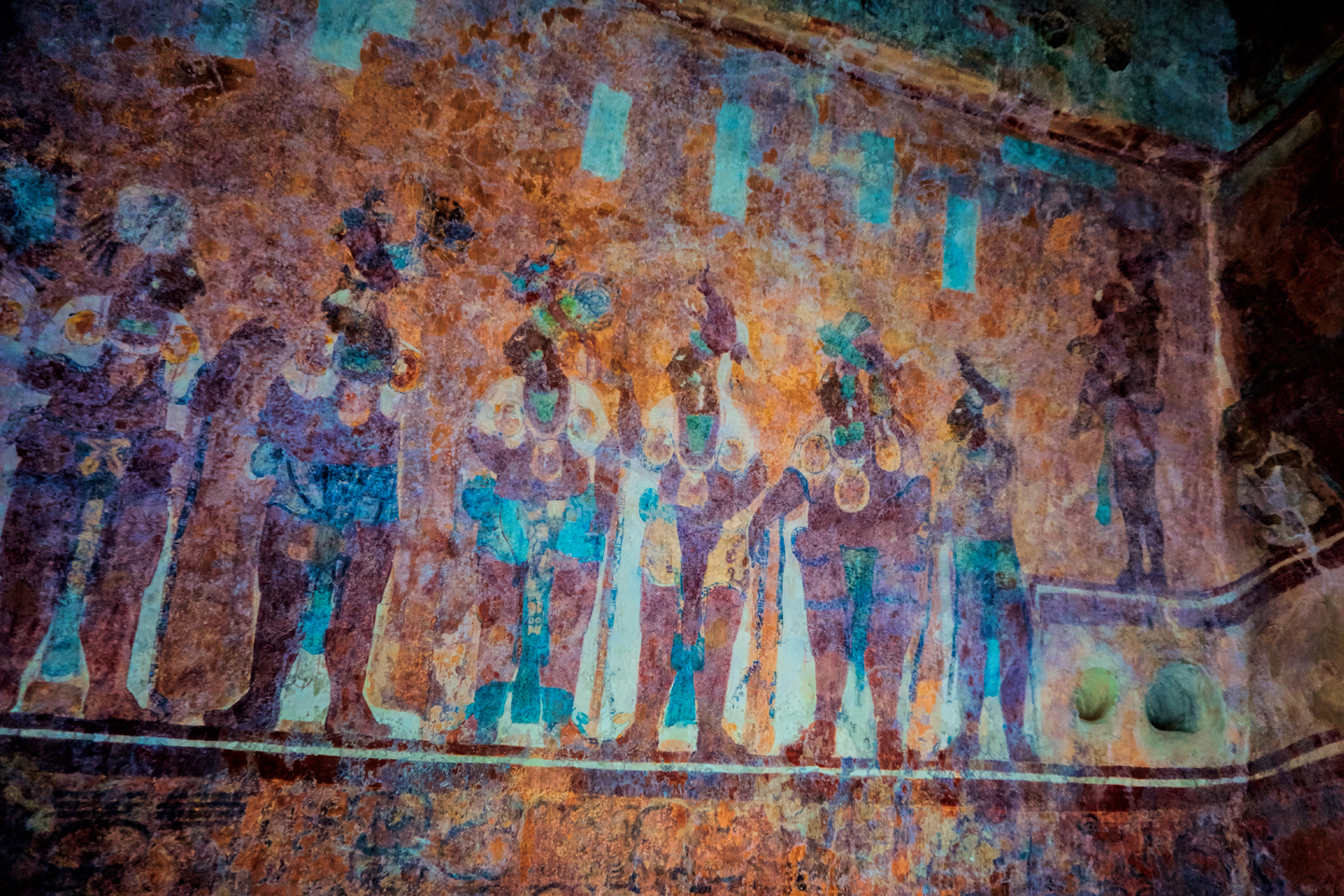

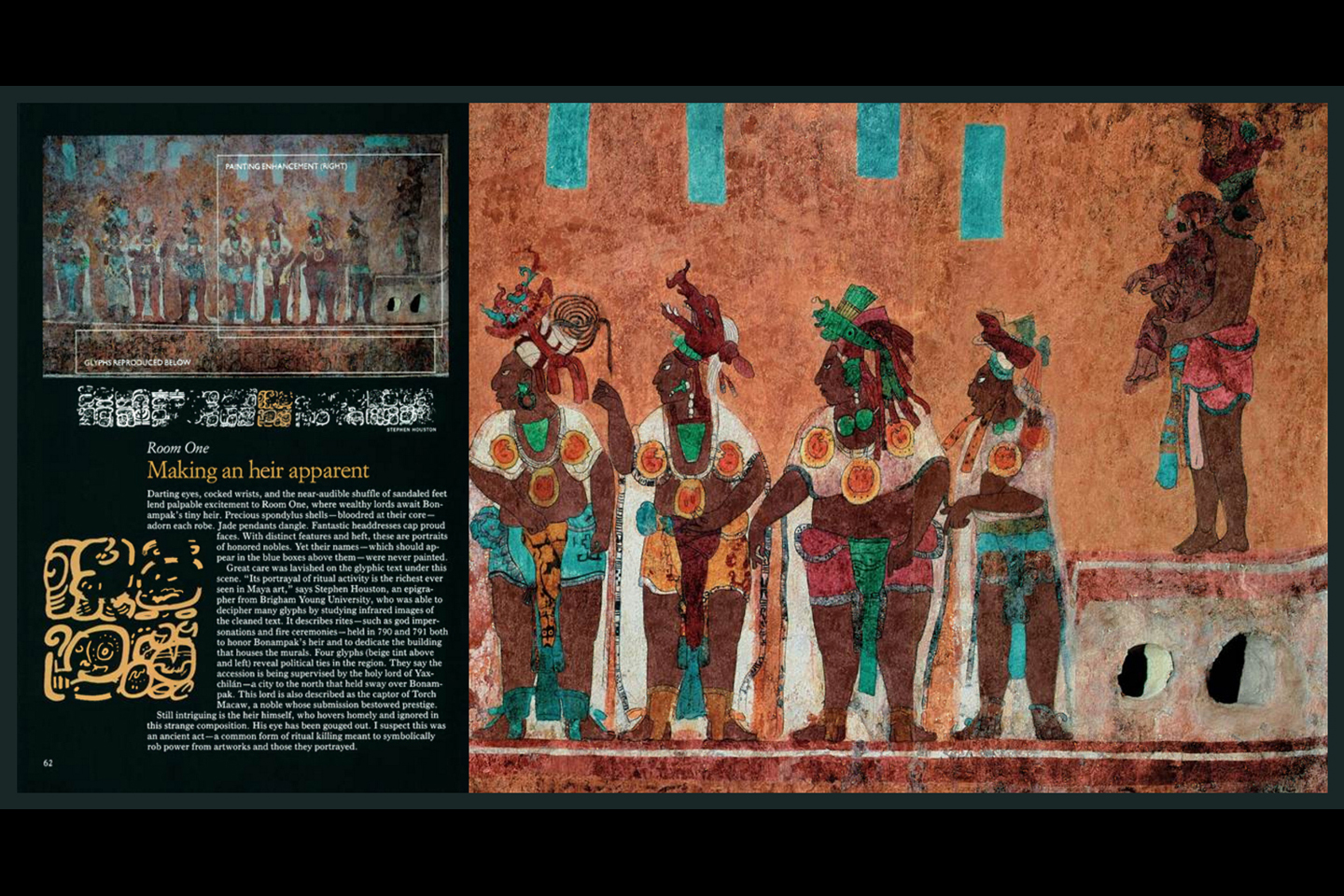

Some sections of the murals are far better preserved than others, and there’s evidence of what appears to be vandalism: faces of some of the figures were deliberately obliterated at some point after the painting was completed.

Deliberately “de-faced” Mayan Lords in Room 3, Bonampak

On other figures, the eyes were gouged out. According to scholars, this was in fact deliberate, but it wasn’t vandalism. Many of these painted images represent specific individuals who lived in that era. The mutilation of their portraits was a way to nullify the power associated with their legacy. It was a graphic representation of shifting political influence, and was not at all uncommon among the Maya. Such “de-facing” is actually thought to predate Mayan culture, as it is a practice that originated with the Olmecs.

The eyes were deliberately gouged in this detail from Room 1

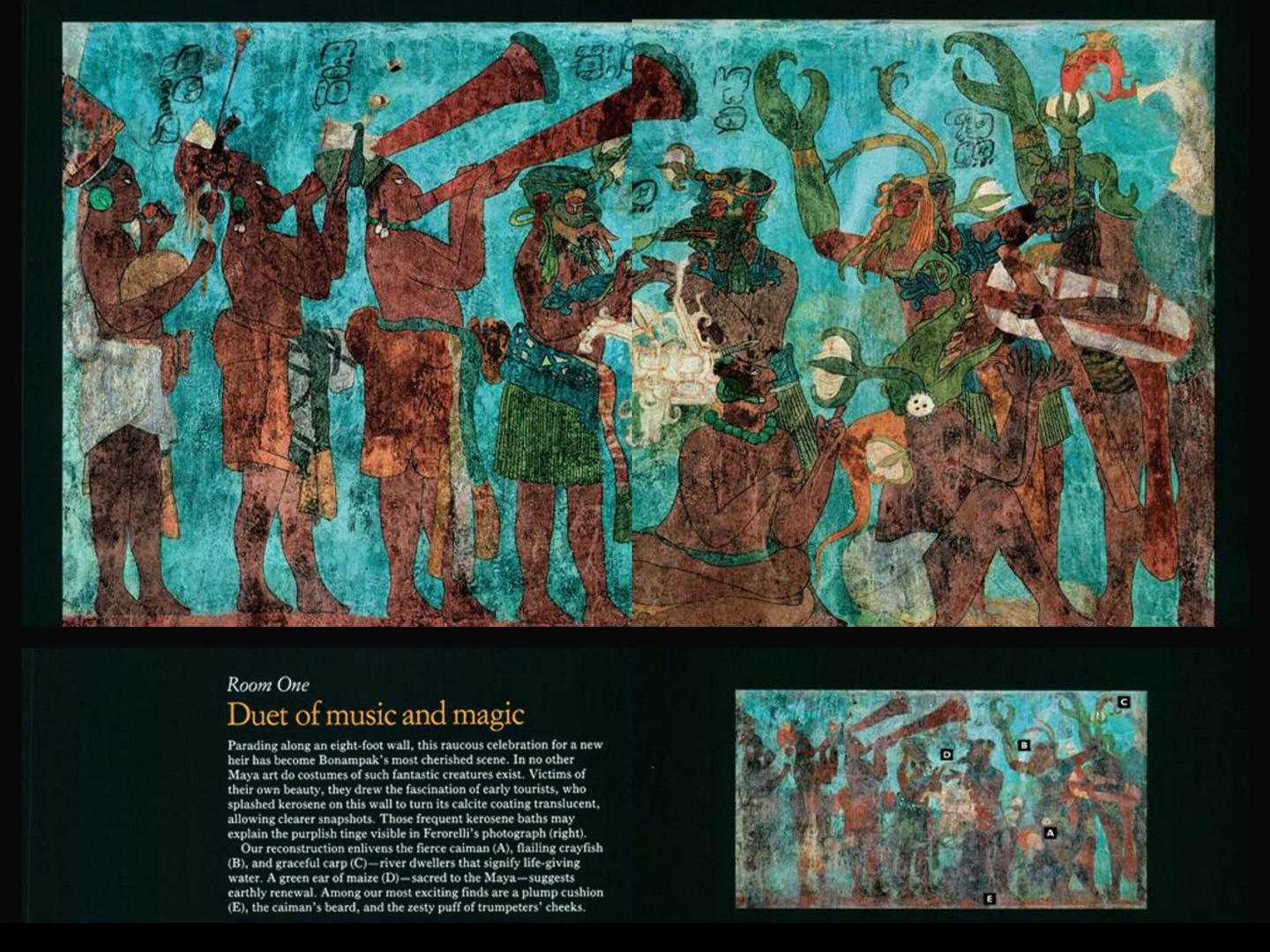

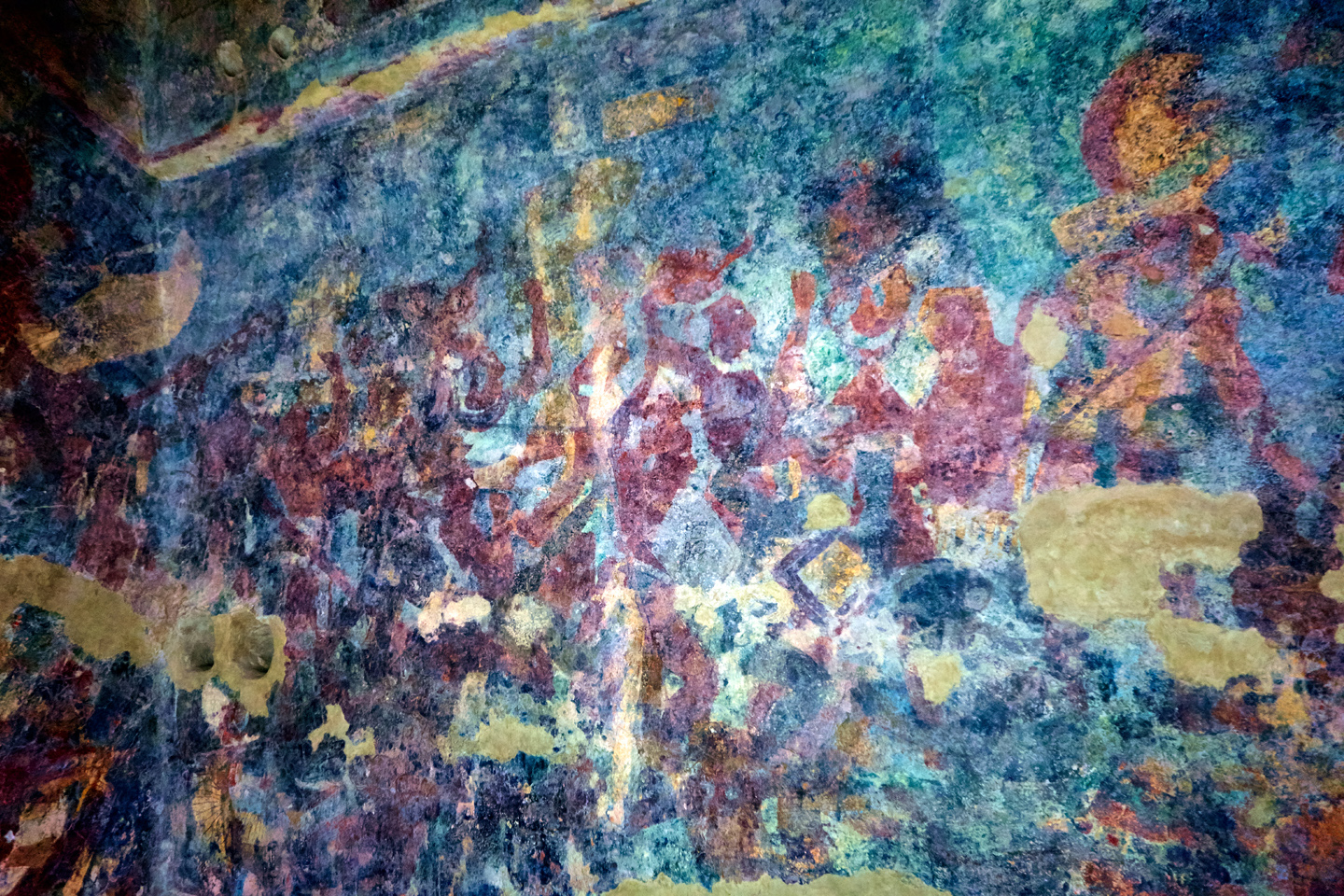

There is other damage to the murals that was not intentional, but much more recent. Early visitors to Bonampak were in the habit of spraying kerosene on the murals, to brighten the colors for their photographs. This practice caused significant damage to many of the panels, but by the time anyone realized that, it was too late to reverse it.

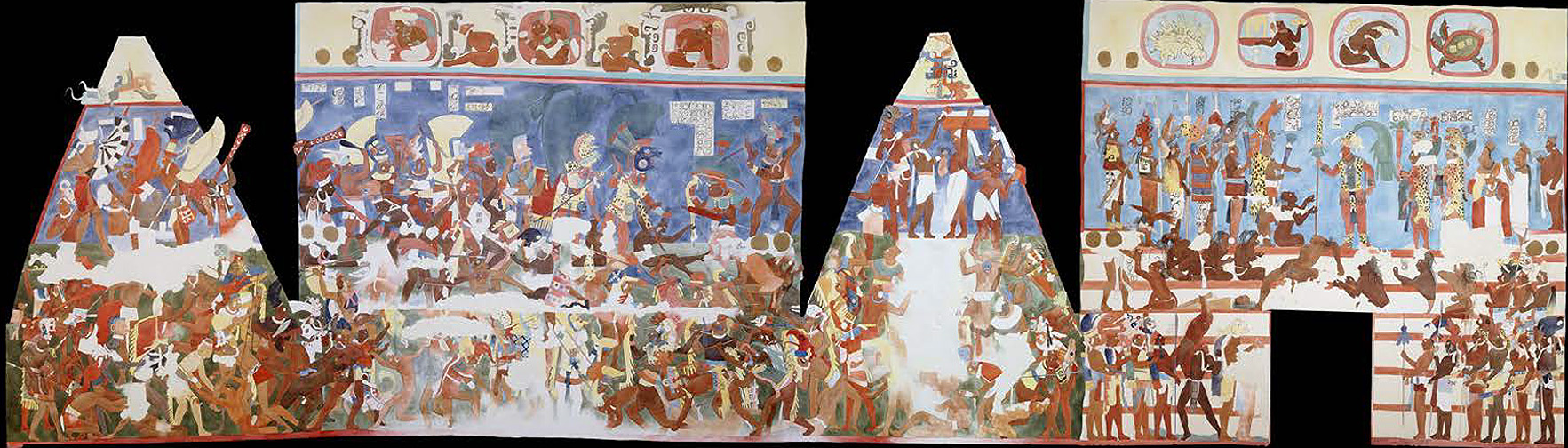

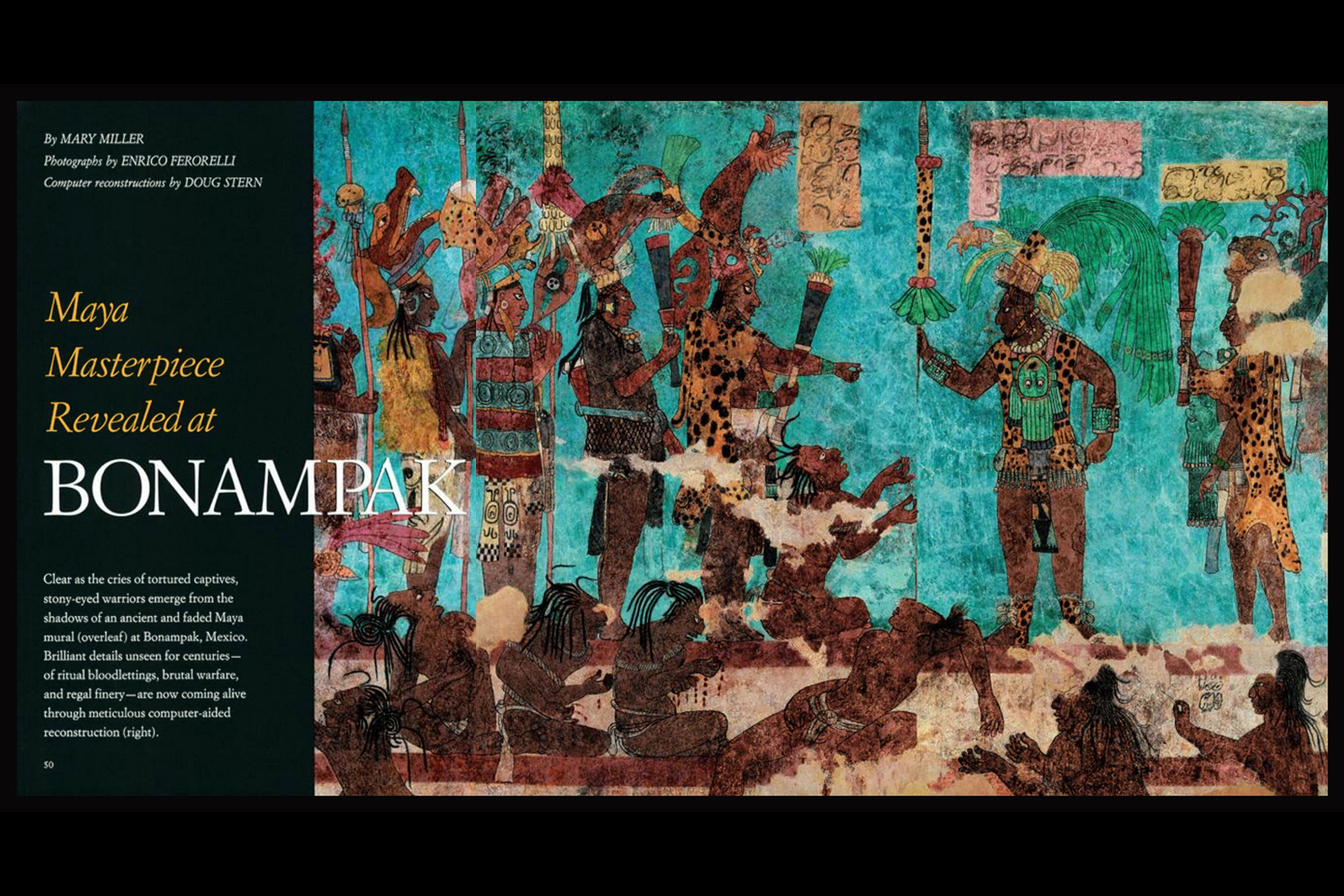

They’ve used modern scientific techniques, infrared photography, and thermal imaging to bring out details in the murals that can’t be seen with the naked eye. Two projects, one sponsored by Yale University, the other by the National Geographic Society have done remarkable work with the murals, using computer assisted graphic techniques to recreate these amazing paintings with something that comes amazingly close to their original glory:

Original photograph from Bonampak. This panel was permanently damaged by early tourists spraying kerosene.

The same scene after restoration, as reported in National Geographic Magazine.

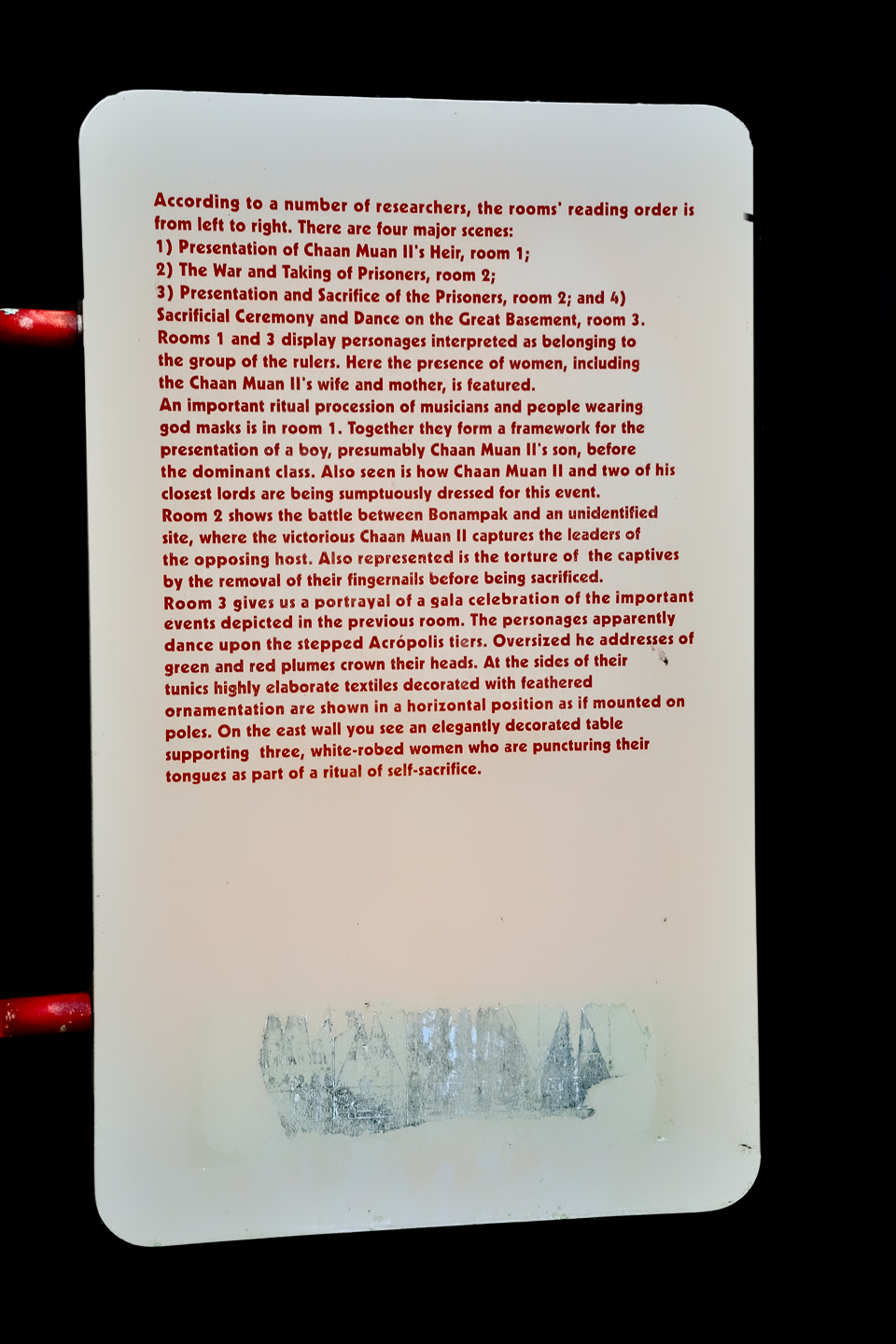

Room 1 is entered through the door on your left as you face the temple, and it is in this room that the remarkable story begins. The paintings travel around the room in four distinct segments, beginning with the panel nearest the floor. We see a procession of lesser nobles, including musicians, and men wearing elaborate god masks, lined up around the walls, against a bright blue background. Above them is a narrow band containing hieroglyphs on one side, and images of captives or menial workers on the other. Next is the widest, most impressive panel, in which we have Chaan Muan II, the Lord of Bonampak, presenting his new son and heir to the nobles of his court. These are clearly important personages, sumptuously dressed, each in a different costume, standing in a line before their ruler; each of the two longer walls features a seperate, but similar scene, against an orange background. Finally, the vaulted ceiling, which is filled with designs representing the Mayan version of heaven, and images of gods.

Reproduction of Room 1, Latin American Studies.org

Room 2 is entered through the door in the center, and presents images that set a much different tone. These are battle scenes, in which the Lords of Bonampak vanquish seemingly helpless villagers for the purpose of taking captives. Captives were the fuel of Mayan society, the energy source that made it work. Slave labor built their monuments, raised their crops, transported their goods, and more. The pool had to be continuously refreshed, because the bloodthirsty Mayan religion required a constant supply of expendable humans to serve as sacrificial offerings to their gods. In one panel, Chaan Muan II, dressed in all his finery, grasps a terrified villager by the hair, as the man struggles desperately to free himself. In another, a row of bound captives sit weeping in pain, their fingertips dripping blood after their nails were ripped out.

Clearly, it wasn’t good to be on the wrong side of the Lords of Bonampak!

Reproduction of Room 2, Latin American Studies.org

Room 3, last, but certainly not least, is through the door on the right. This is where the prisoners captured during the battles in Room 2 are sacrificed. There are celebrations, with music and dancing and gigantic hats that look like a collaboration between Dr. Seuss and Hieronymus Bosch. One of the upper end panels depicts a particularly graphic scene in which a group of noble women pierce their tongues to draw blood, as an offering to the gods. The heir to Chaan Muan II, presented to the court by his father in Room 1, is seen here with his mother, preparing to participate in his first bloody sacrifice.

It’s almost unimaginable, but artwork such as this must have covered the walls of every important building in the Mayan world, documenting the lives and the fantasies of all their kings in graphic, colorful detail. The Mayan cities as they appear today, pyramids and temples built of weathered limestone, the only color coming from vegetation sprouting in the cracks between the blocks; those ruins bear no more than a passing resemblance to the original constructions that stood on those crumbling foundations. The Maya loved color. The evidence of that is abundantly clear, especially when we look at the Bonampak murals. These places would have truly been something to see, back in their glory days. As long as you weren’t on the losing side of one of those one-sided battles.

IF YOU GO:

Getting to Bonampak requires some effort. There is no town of any significant size anywhere near the ruin. There are, however, bus tours that leave from Palenque. It’s a three hour ride in each direction, and with a couple of hours at the site, that makes for a very full day. Other tours require two full days and include a visit to Yaxchilan and an overnight stay at a jungle lodge. Those tours are a bit on the pricey side, as they include not only the bus, the tour guide, and your lodging, but also a fairly expensive boat ride to Yaxchilan. There are public buses that will take you to within a couple of miles of the ruins, or, best alternative, rent a car. No matter how you get to Bonampak, there’s one hard, fast rule: don’t travel that road at night. It gets incredibly dark, there are numerous hazards on the highway–everything from animals in the road to potholes larger than your car, plus, it’s a border area, remote, and somewhat lawless, and there are goings on after nightfall that you really don’t want any part of. For that reason, the tours leave Palenque early in the day, and return before dusk. Any tours that extend for an extra day will have you safely in your hotel long before sundown.

One other thing, no matter how you go, the last five miles will be in one of the small vans that ferry visitors from the parking lot to the ruins. This isn’t optional–no private vehicles are allowed on that last section of road, and it’s a bit too far to comfortably walk it. Once the van drops you off, you’ll still have to walk a short distance across an open area.

Beyond the parking area, you cross an open field before you reach the plaza.

Just beyond a line of trees, you come to the Grand Plaza. What you see is what you get: note the Temple of the Paintings on the right in these photos. The ruins are actually more extensive than they appear–only the small section around the Temple of the Paintings has been cleared and opened to visitors.

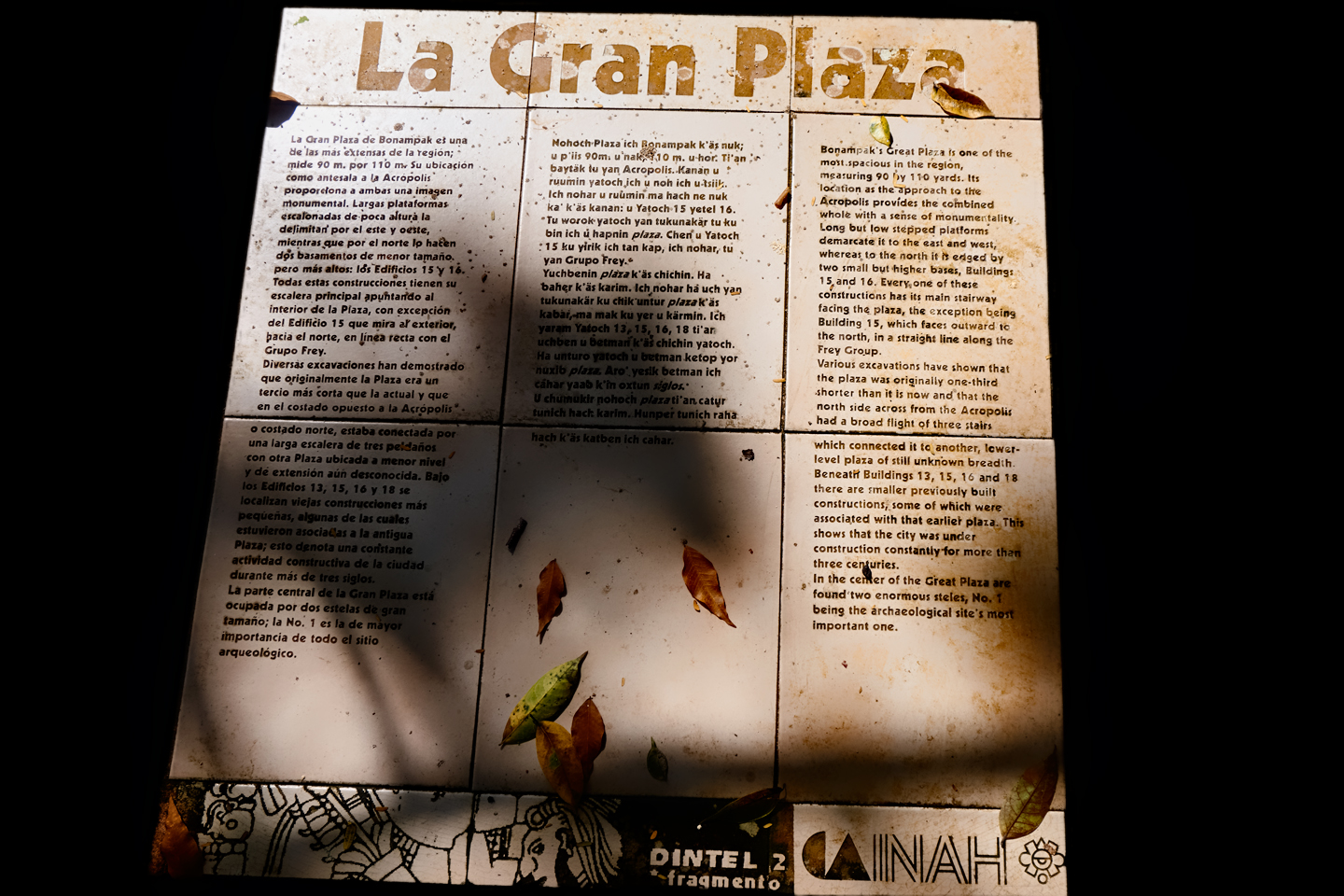

A sign, once again in Spanish, Mayan, and English, describing the layout of Bonampak’s Grand Plaza.

After you climb the steps to the Temple of the Paintings, you’ll be met by the caretakers of the site, all Mayan men from the nearby village, who guard the place as if it were their own. You show them your ticket, then you get in line to view the interiors. There’s a seperate line for each of the rooms, and no more than four people will be admitted to any of the rooms at the same time–there’s too much moisture in our breath, and it’s bad for the paintings. No bags or backpacks are allowed (not even camera bags), and, while you can take all the pictures you like, you can’t use a flash. Ever. Not even a little one. No tripods, either. When I traveled to Bonampak, in October of 2015, my friend and I were the only visitors during the time we were there, so all of that was reasonably casual, but I’m told that when the site is crowded, the rules are quite strictly enforced. On busy days, the maximum time allowed in each room is just twenty seconds per person, so if you want photos, you’ll have to work fast!

Provided it’s a sunny day outside, there is just enough light in those rooms to hand-hold your shots and still come away with usable images, but only if your equipment is up to the task. If photos are important to you, I’d recommend using a good digital camera, rather than your cell phone. (Unless you have the very latest version of phone, something that you’re certain will work well in very low light situations). With a DSLR or Mirrorless camera, shoot with a fast wide angle zoom, set your camera to a high ISO, bracket your shots, and cross your fingers, because there’s luck involved. It’s important to remember that a visit to a place like Bonampak is not just another photo opportunity. Think about where you are, and what you’re seeing; then try to imagine a world where the scenes in those paintings were actually happening!

The Bonampak murals are like nothing else in the Mayan realm, and well worth seeing for yourself. No photo can do them justice. You have to view them in context, in order to really appreciate them for what they are: simply extraordinary.

Click any of the pictures in these slide shows to enlarge them all to full screen, with captions:

(Unless otherwise noted, all of these images are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.)

READ MORE LIKE THIS:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I've ever seen. There's a powerful energy in that spot--maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps--but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I've ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I've ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Photographer's Assignment: Chichen Itza

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Coba and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Coba was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Becan and Chicanna: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

Mexican Road Trip: How to Plan and Prepare for a Drive to the Yucatan

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancun, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancun from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

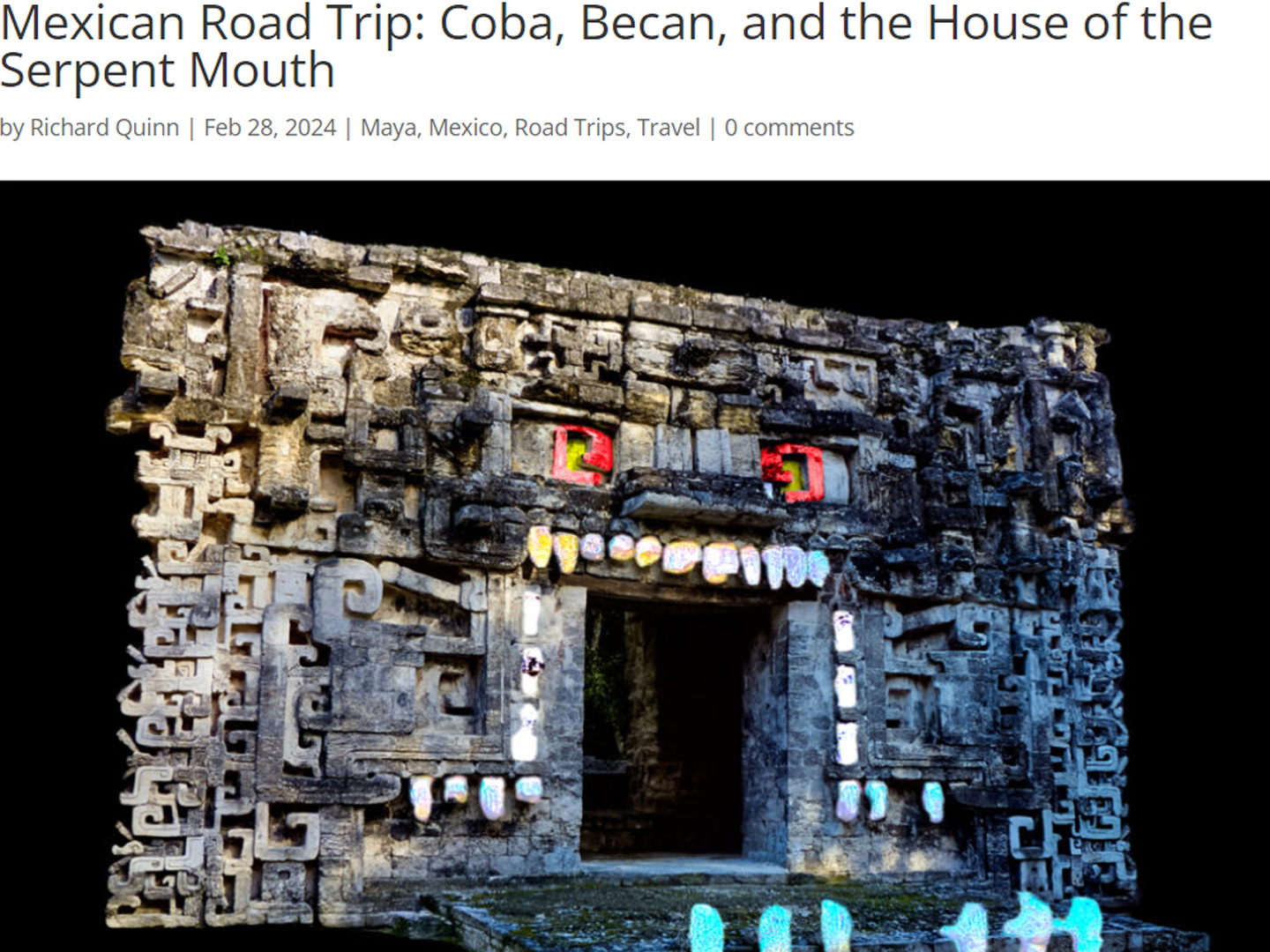

Mexican Road Trip: Coba, Becan, and the House of the Serpent Mouth

After Tulum, we drove south, then west, headed back to Campeche. Along the way, we visited some Mayan ruins that are less well known, starting with Coba. the major Mayan city northwest of Tulum, followed by Muyil, Becan, and Chicanna. Each site was unique, and each of them added another piece to the puzzle of the ancient Maya.

(This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication: March 2024)

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Campeche, Edzna, and La Guaranducha

(This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication: April 2024)

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico's Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they've adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It's a wonderful, colorful parade that's all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

A shout out to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. "Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins" was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after "Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali." We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Road trips with old friends are the absolute best. We laugh and we laugh until we run out of breath, and laughter is good for the soul!

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments