Cartagena, Colombia is one of my all-time favorite cities. It has a gorgeous setting, on the shores of the Caribbean, and with the battered walls of the old town, and the Spanish forts with their rusty cannons still in place, it has a swashbuckling history you can reach out and touch. What I love most is the contagious laid-back vibe that leaves you smiling, even when life isn’t exactly going your way. I have both good and bad memories of Cartagena, deep memories, and like many things in life, the earliest are the best. My first visit, in November of ’71, I was traveling with my friend Paul, an ex-con, ex-Marine, expatriate from San Francisco. Paul was a self-professed grave robber, what the Colombians called a guaquero, determined to strike it rich digging up archaeological treasures, and he was actually rather good at it. We’d been working together, and I’d tagged along on several of his digs, including a recent adventure at a Tairona site near Santa Marta (see Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent). He’d had some luck at Bahia Concha, even found a bit of gold, so he had money in his pocket, and he was in the mood to celebrate.

There was a hotel, the Del Caribe, the best in town in those days, right there on Bocagrande, a beautiful beach with clean white sand. It was built back in the ’40’s, and it was oozing tropical elegance, almost like stepping back in time to Havana before the Cuban Revolution. Basic rooms ran 500 Pesos a night–$25 U.S.–which was ten times the cost of other hotels in that time and place, but still low enough that Paul figured he could afford it. It was most definitely the fanciest digs I’d ever stayed in. They had peacocks running loose in the garden, an outrageous swimming pool, and a bar that was straight out of Casablanca.

We were sitting there, drinking ice cold bottles of Heinekin, half expecting Humphrey Bogart to come walking around the corner, when Paul almost choked on his beer. “Did you SEE that?” he asked in a stage whisper, his eyes very wide.

I turned, as discretely as possible, and noticed a guy, possibly an American, with a good looking Colombian woman on his arm, taking a seat at a table in the corner. “Nice,” I said with a shrug. “But you should check the view out the window. The babes out there are all wearing bikinis!”

“I didn’t mean the girl, Chico. Did you see her necklace?“

So I adjusted my position, and took a closer look:

My own eyes went wide, and I let out a low whistle. “Is that what I think it is?”

“A nugget,” said Paul. “A gold mother loving nugget, and the way it’s hanging into her cleavage it must weigh half a pound. Notice anything about her escort?”

“The guy? Not really, why?”

“That dude’s got a tan like an old leather boot. Put that together with a half pound gold nugget, my guess says we’ve got a prospector who has done very well for himself. Come on. I’m going to buy those two their next round.”

We spent at least two hours with the couple, Kent Vance, originally from Colorado, and Claudia, his brand new, significantly younger Colombian wife. Paul had totally nailed it: Kent was a gold miner. He’d spent the last couple of decades in South America, most of that time in Colombia, and the nugget Claudia was wearing around her neck came from his most recent mining claim. He’d been working with a portable dredge in the jungle along the Pacific Coast, and he’d found one of those spots that an old prospector’s dreams are made of. His claim was producing upwards of thirty pounds of gold every month, and even at the black market rate of fifty bucks an ounce, thirty pounds of gold was serious business. Word got around, and the next time he came out of the jungle for supplies, a squad of Colombian soldiers was waiting. He wasn’t doing anything illegal, but that didn’t stop them from demanding a hefty bribe, and he was in no position to refuse. He knew they’d be back for more, probably followed by the National Police, customs patrols, and inspectors from the Bureau of Mines, all expecting a mordida, just a small bite of the pie. The yield on his claim had been dropping anyway, so he pulled up stakes and beat feet out of there while he was still ahead of the game.

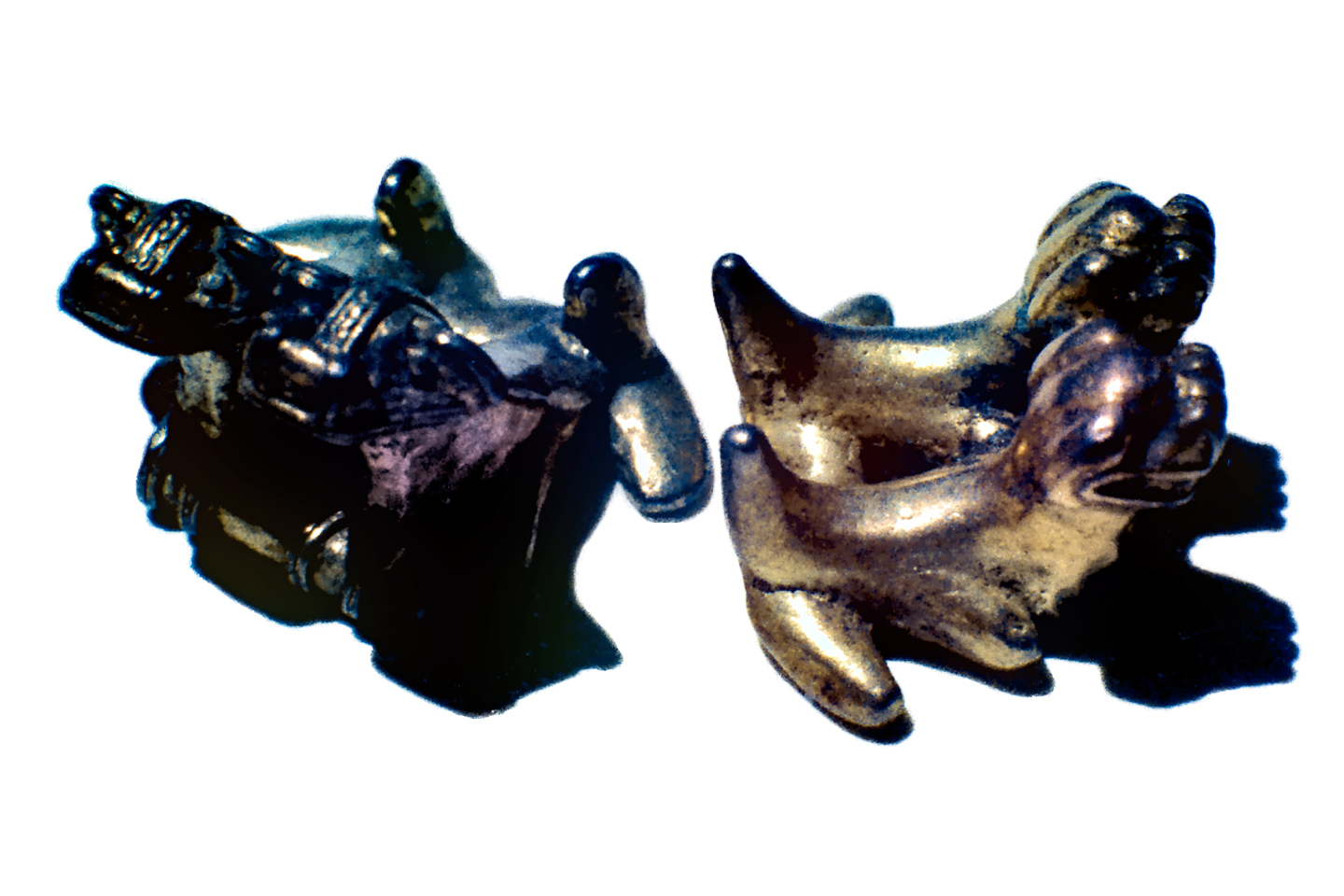

Now it was Paul’s turn to brag, something else he’d always been rather good at. He started by producing a pair of Tairona ornaments from his bag, part of his haul from the dig at Bahia Concha: a matching set of twinned gold jaguars, each of them about three quarters of an inch long, and probably 700 years old.

Kent was impressed, and wanted to know how much they were worth. At that time, gold artifacts were valued by their weight, factoring in the purity of the gold. Paul’s gold jaguars were extraordinary, but small, and light, and made of a gold and copper alloy called tumbaga. On the local market, he’d be lucky to get fifty bucks for the pair, so he held on to them, reasoning that he could sell them to a wealthy tourist for at least two hundred. “These little guys would look great on a necklace,” said Paul, flashing a conspiratorial wink at Claudia.

After a bit more banter about gold artifacts, Kent reached into the inside pocket of his jacket, and pulled out a handkerchief. “I think it must be fate that I ran into you guys,” he said, carefully unfolding the square of cloth. “Can you tell me anything about these?”

Paul studied them, then turned toward me, one eyebrow raised in that quizzical expression he used, when he figured I might know something that he didn’t. In this case, he was right.

“Nice set of fish hooks,” I observed. “Too beat up to be fakes, so they’re old, maybe seriously old. You said you were working on the Pacific Coast? Did you find them, or buy them off somebody?”

“I bought ’em,” he replied. “Along with some scrap pieces from the same source. The biggest was part of an armband, shaped like a coiled snake–can’t show you that because I gave it to a friend in Popayan, to settle an old debt.”

“Where did you say they came from?” I asked, poking the obviously ancient fish hooks with the tip of my finger.

“The same place I was working my dredge,” he replied. “In the middle of absolute nowhere. There were some colonists out there, four families living in stilt houses on a little patch of high ground, trying to hang on for enough years to qualify for free land under Colombia’s homestead laws. Everybody in that area pans for gold in their spare time; that’s why I went there in the first place. One of the guys was missing most of his right arm, but he developed this crazy one-handed sifting technique that put his two-handed neighbors to shame. He’s the one who found the fish hooks and the arm band, while he was panning in a stream that was maybe half a day’s hike from his house. He kept it all in a cigar box; his most prized possessions. Sold me the lot for a thousand Pesos, but from what you’re telling me, I might have got snookered!”

“Live and learn,” Paul said with a grin, signaling the bartender to send over another round of drinks.

Kent went on to tell the rest of the story. Before the greedy authorities chased him off, he’d had plans to stay in the area longer. He’d chartered a helicopter in Buenaventura and used it to fly a grid around his camp, looking for a better spot to site his dredge. Remembering those gold artifacts, he helped the pilot locate that particular creek, and they followed it upstream to see if there was anything visible that might indicate an ancient town or village. This is some of the thickest jungle in the world, so of course there was nothing obvious, but there was a hill, not too tall, that seemed flat on the top, and there were no old-growth trees of the sort that crowned all the other hills. It was almost as if that hill had been cleared at some point, which seemed very odd. He made a note of the coordinates, planning to check it out from the ground–but he never got the chance.

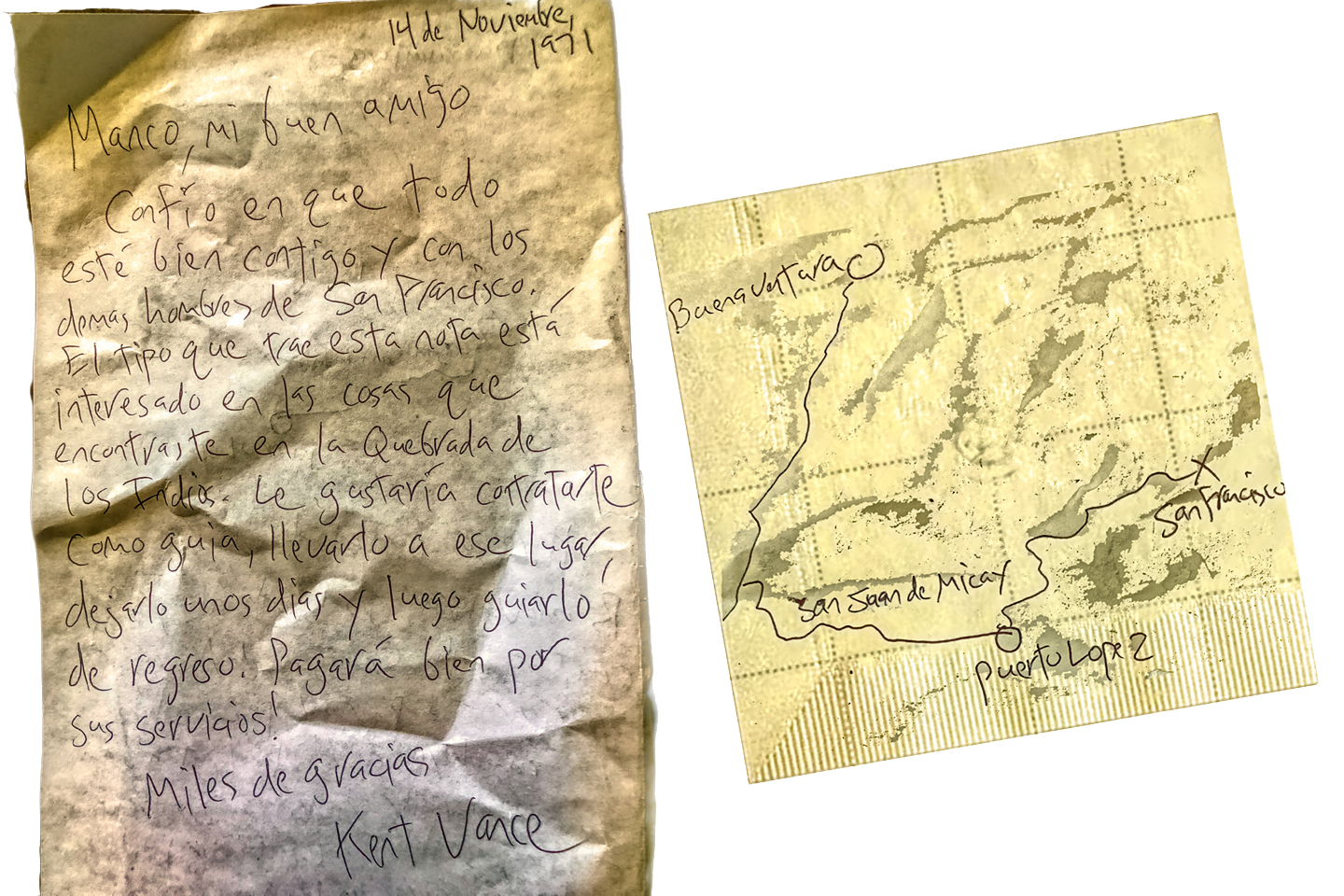

Numerous tall tales and several beers later, Kent and Claudia had to leave, but not before Paul worked out a deal. Kent went away with Paul’s gold jaguars. In return, Paul got $100 U.S., a handwritten note, and a map drawn on a cocktail napkin. The note was addressed to the man who had panned those gold fish hooks out of that stream, deep in the Cauca jungle. The map, along with Kent’s verbal instructions, were supposed to lead us straight to that guy, a one-armed homesteader who went by the name El Manco.

Neither Paul nor I knew the first thing about organizing an expedition into a place like that, but we had a friend in Cali, Jaime Errazuriz, who was well acquainted with Colombia’s Pacific Coast. Jaime was a wealthy architect who had shifted full time into the antiquities business, and owned high-end Pre-Columbian art galleries in Cali and Bogotá. He’d told us stories about digs he’d organized in the Tumaco area, just south of where we wanted to go, so we figured he might be able to give us some pointers.

Paul was eager to move on this thing, so we flew to Cali from Cartagena, and took a taxi straight to Jaime’s gallery, just down the street from the new Inter-Continental Hotel. We told him the story, showed him the note, and the man got a sparkle in his eye that damn near lit up the room. According to Jaime, Kent’s flat-topped hill was almost surely a tola, a mound built by the Tumaco people to raise their communal houses, temples, and burial grounds above the flood plain. No tola had ever been found that far north, but if gold artifacts were literally washing into the stream, who knew what else might be buried in that mound?

Jaime was more than happy to help us organize the trip–on the firm condition that we allow him to join us. Paul quickly agreed, especially after Jaime offered to pay for all the transportation, which was likely to be the biggest expense. On the down side, we wouldn’t be able to leave right away. The Christmas shopping season was fast approaching, and that was the busiest time of year for Jaime’s galleries. That meant the soonest he’d be available would be the second week in January. We agreed to that as well, and at that point, Jaime took over the planning.

I flew home to the States in December, to spend Christmas with my family, and to touch base with my professors at Antioch College, where I was in my fourth year, closing in on a degree in Anthropology. I did some fast talking, and made provisional arrangements to use the expedition into the Cauca jungle as the basis of my senior project, an independent study that was a bit like an undergraduate thesis. Depending on what we found, and on how well I wrote it up, my original research and the resulting paper was potentially equivalent to a full semester of academic credit. My proposal was pretty far outside the usual box, even for a progressive institution like Antioch, so they didn’t say yes to it outright. Instead, they scheduled a meeting for me with the faculty of the anthropology department at one of Antioch’s affiliates, the Universidad de Los Andes in Bogotá. If those local experts agreed that my project was viable, they would enroll me as an exchange student, and one of their professors would serve as my advisor. All of that worked out even better than I’d hoped, and it was very much to my advantage.

Everyone I talked to in those meetings expressed grave concerns for my safety, especially the anthropologists in Bogotá, who painted a very stark picture of the dangers I would be facing. They were right to be worried, but from my perspective, this was a once in a lifetime opportunity. There was a possibility, however slim, of a lost city in the jungle, complete with golden treasures, and there was nothing anyone could have said that would have stopped me from going after it.

By the time I rejoined my friends in Cali, everyone was ready. The expedition had swelled to five members. Ed Williams, another of Paul’s friends, had talked his way onto the roster, and Jaime was bringing one of his employees, Gustavo Benavides, a combination body guard and personal assistant.

When I was at home in Arizona, I bought an expensive metal detector, a top-of-the-line device incorporating the very latest in early 1970’s technology, purchased directly from the Phoenix-based manufacturer. In its normal configuration, it could reliably detect both ferrous and non-ferrous metal to a depth of at least six feet, and there was an optional larger sensor, the size of a hula hoop, that you could use to detect larger amounts of metal to a depth of thirty feet. I hauled it all down with me in my luggage, the fragile hoop presenting some serious challenges, on the flights, as well as in Colombian customs, but I was quite a smooth talker, back in those days, and I got it through. That metal detector turned out to be a huge contribution, because at that time, that sort of equipment simply wasn’t available in Colombia, not at any price.

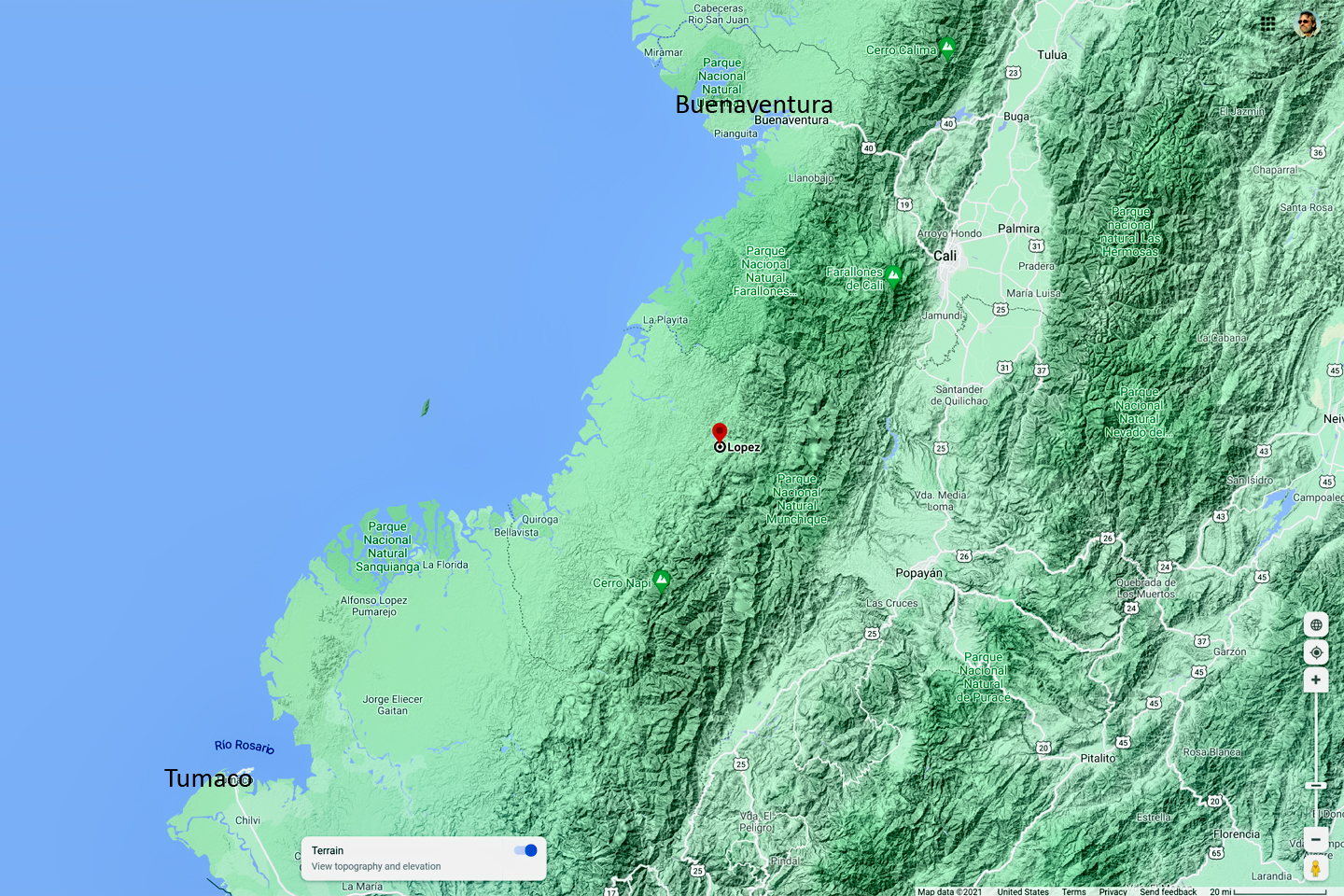

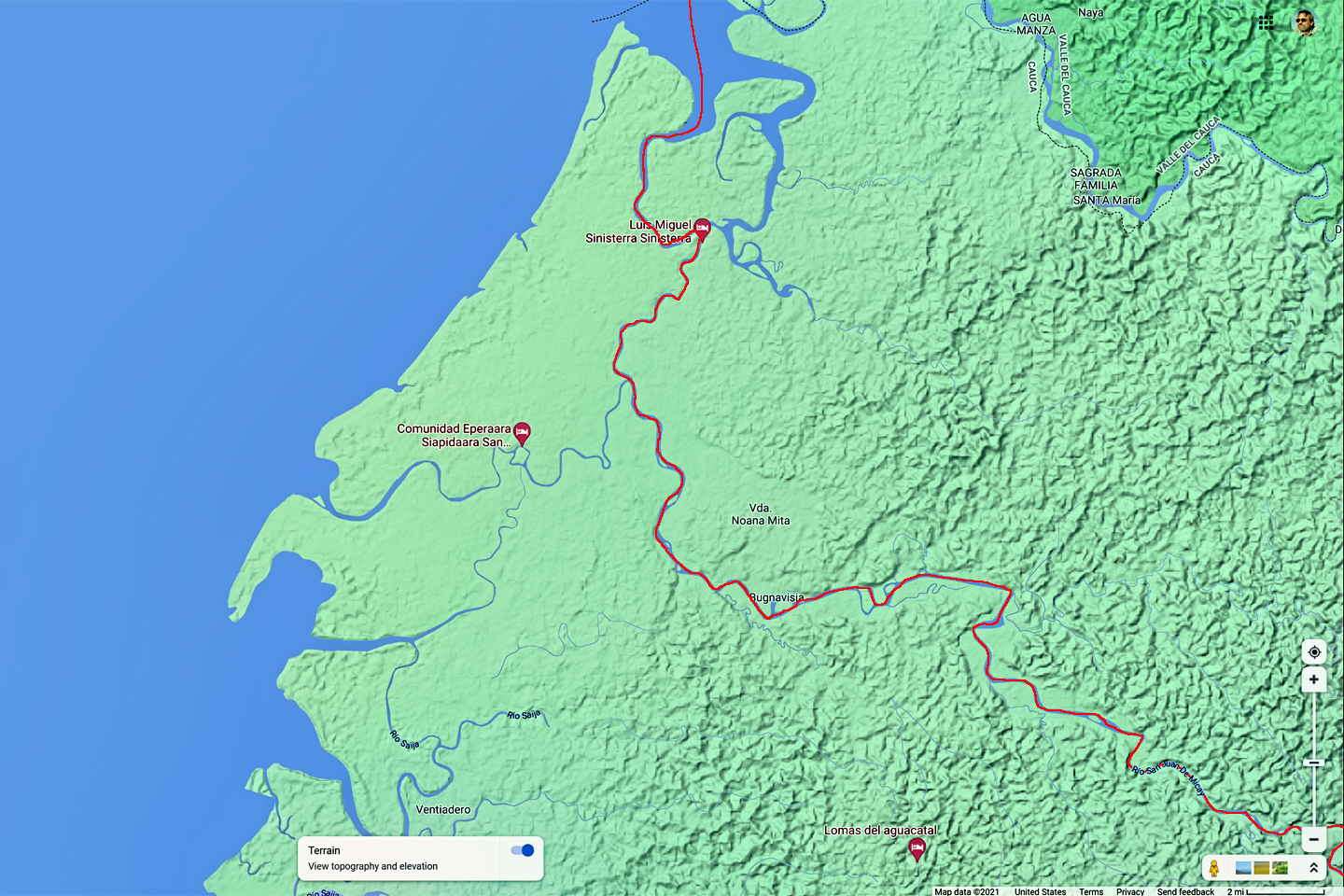

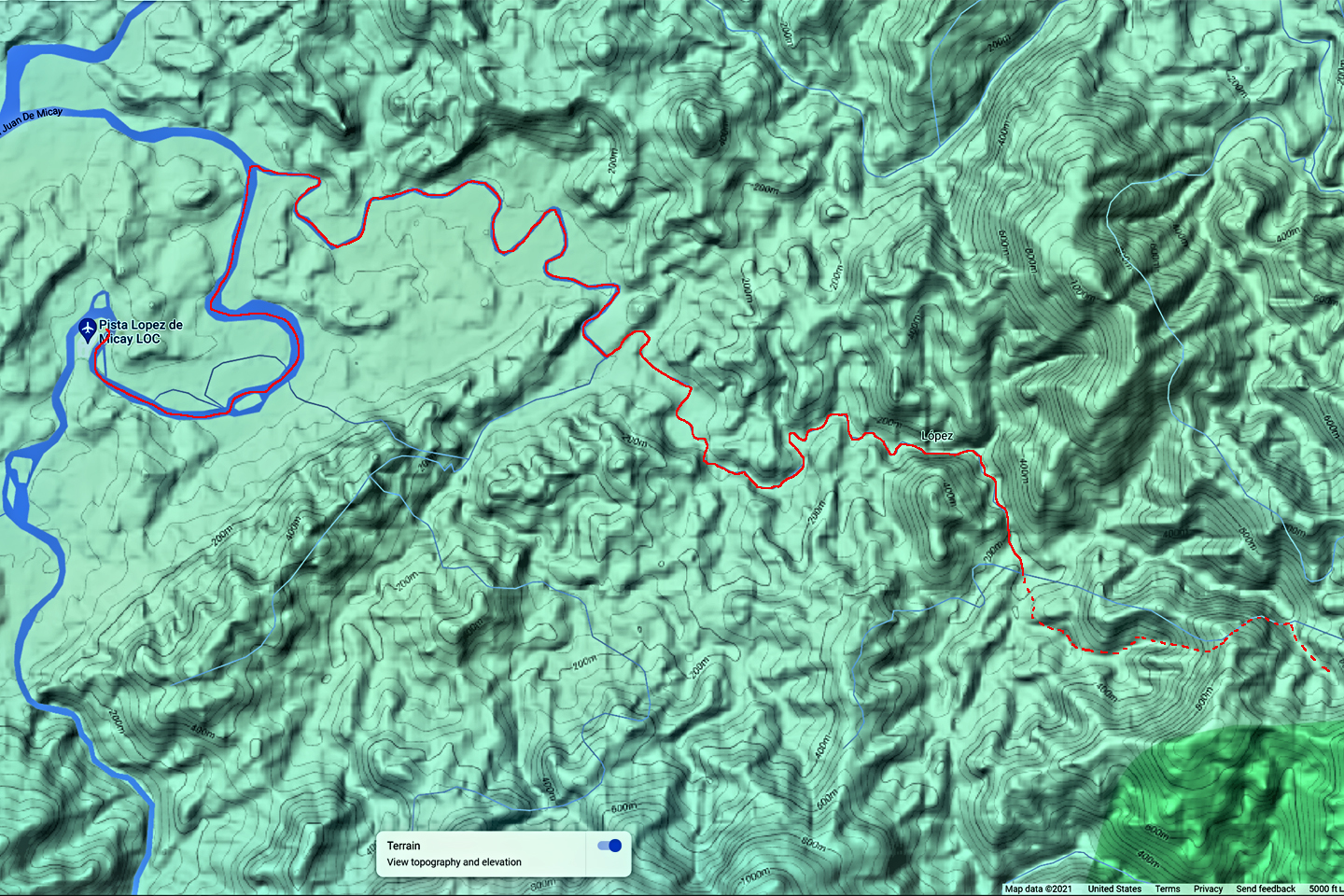

Jaime provided just about everything else–a tent, camping gear, and waterproof duffels for our supplies. He’d done some research, and informed us that Lopez de Micay, our preliminary destination, was officially the rainiest occupied place in the country, possibly in the entire world, registering as much as 500 inches of precipitation in an average year. “So we should expect to get wet, and to stay wet for pretty much the entire trip,” he said. I doubt he had any idea how prophetic those words would be.

In January of 1972, Buenaventura, Colombia’s only major port on the Pacific Coast, was a shit hole. It looked like a shit hole, and worse, it smelled like a shit hole, largely because of the raw sewage that poured into the harbor from the slums that housed most of the city’s population. The port was located just a bit inland, in the mouth of a jungle river, surrounded by sulfurous, stinking swamps. I hear it’s better now in some ways, but worse in others–like most of the rest of Colombia. In January of 1972, the area near those docks was pretty damned sketchy, and we were very glad to be riding through it safely locked into Jaime’s Land Rover; we were likewise very glad that both Jaime and his body guard were armed to the teeth.

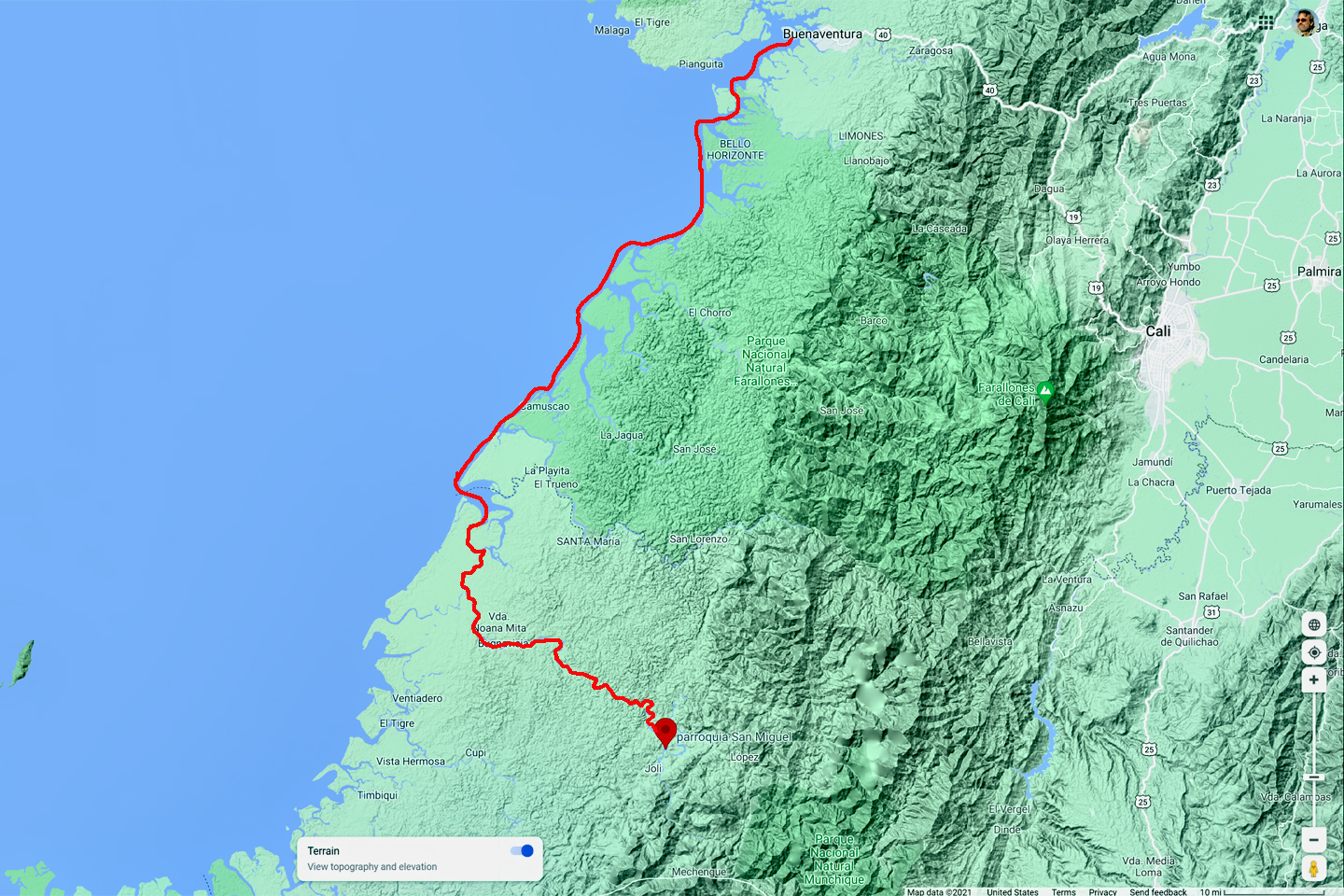

Arrangements had already been made for a boat that would take us south along the coast, and then up the San Juan de Micay River to Puerto Lopez, following the old prospector’s instructions. The same boat would return ten days later to take us back to Buenaventura. All that sounded pretty great, until we saw the boat. It was really more of a big canoe with an outboard motor, which, at that moment, was partially disassembled, and Ivan our boatman, shirtless and sweating profusely, was banging on it with a large wrench, seemingly at random. He gave the starting cord a yank, to no avail, so he gave the motor three more hard whacks, and tried again. The outboard belched black smoke, spluttered, and died. The third try was the charm; the motor continued spewing and spluttering while he replaced the cowling, and invited us to climb aboard.

Ivan had a helper, Mauricio, a skinny kid who couldn’t have been more than ten or twelve. Between the two of them, the five of us, extra cans of fuel, and all of our gear, Ivan’s little boat was packed to the gunwales, and riding low in the water. That was okay, he assured us, because we wouldn’t be crossing open ocean on this trip. We were going to hug the shore and thread our way through the tangled maze of mangroves, smooth water all the way. This route was his specialty, and he could follow it blindfolded.

Once we got out into the open, and away from the docks, most of the stink blew away, and the further we got from shore, the hard edges of the city blurred and softened, until you could almost believe that it wasn’t so bad after all. The day was gray and overcast, like most days in that part of the world, and it was no surprise when it started to rain. What began as a drizzle dialed up pretty quickly into a steady pour. Ivan’s boat was lacking a canopy, which wouldn’t have done us much good in any event. We all had rain gear of one sort or another; mine was a brand new Gore-Tex parka that proved to be worth its weight in gold. Our provisions and equipment, including my two Nikons and that precious metal detector, were packed away in the water tight duffels, so we were in reasonably good shape. Jaime’s prediction about getting wet and staying wet came true in the first hour of the trip–and we hadn’t seen nothin’ yet!

There was one place in particular where the shoreline opened up into a bay, and we did cross a stretch of open water, to avoid taking the long way around. It was there that we were hit by the most powerful cloudburst I’d ever experienced, a cosmic firehose pointed straight down at our boat from somewhere in the heavens. Mauricio was baling like our lives depended on it, so Gustavo grabbed a bucket to help him, while Ivan did his best to stay on course in the downpour. When we re-entered the wall of mangroves on the far side of the bay, he realized he’d missed his channel through the swamp, and we lost an hour backtracking and reorienting in the still pouring rain.

The San Juan de Micay was a good sized river with multiple channels, so it was a good thing that Ivan knew where he was going. The hour that we’d lost put us behind schedule, and between the bad weather and the excess weight, he hadn’t been able to make up any time. Cruising up the river was much nicer than motoring through the mangroves, but we were running against the current, dodging logs and other hazards in the chocolate brown murky water, so Mauricio stayed in the bow, calling out IZQUIERDA and DERECHO and IZQUIERDA again, until the poor kid started losing his voice. By the time we came in view of Puerto Lopez, a handful of winking lights on the riverbank, it was almost full dark. You don’t want to be out on those rivers after dark, and I could see the relief on Ivan’s face when he tied his boat to the rickety dock.

It wasn’t much of a town. A couple dozen buildings, some on barges tied to the bank, the rest on stilts and connected by boardwalks, which is the only way people can live in a place where the river might rise six feet overnight. The total population was only about 100, but there were hundreds more colonists in the general area, and Puerto Lopez was where they all came for supplies. There was one general store, lit up like a Christmas tree by a thumping diesel generator that came on just as we pulled in, and Jaime headed straight over there to talk to the proprietor, who was standing in the doorway, sizing us up. I remember being a bit startled to see that he was Chinese–though I have no idea why that should have surprised me.

Lopez didn’t get many visitors, so our arrival was a big deal; nobody had ever so much as imagined that many gringos all in one place, and they were in awe of Paul’s friend Ed, who was 6′ 3″, with a bushy red beard unlike anything they’d ever seen. Everyone in town wanted the honor–as well as the income–from offering us overnight lodging, so we split up, each of us in his own hammock, in four different back rooms, while Ivan and the boy slept in the boat.

After a long night filled with a symphony of strange screeches and squawks, and winged battalions of bugs, some the size of tennis balls, flinging themselves against the doubled layers of my mosquito netting, I don’t think I’ve ever been quite so happy to greet the dawn. My host offered me a battered tin cup filled with the worst coffee I’ve ever tasted. I accepted it with solemn thanks, but discretely poured it out the open window into the river the moment his back was turned. My clothes were still wet from the day before, especially my jeans, but there was no point in changing until we got where we were going. The sun wasn’t really up yet, and there was a damp chill in the air when I made my way down to the dock, where everyone else was already gathered. Ivan and Mauricio were saying their goodbyes, headed back to Buenaventura, with a promise to return for us in exactly ten days.

The rest of our journey required smaller boats, and Jaime, ever efficient, had already made the arrangements. We transferred our gear into three dugout canoes, and then very carefully climbed aboard, Jaime and Gustavo in the first boat, me and Paul in the second, and Ed taking up the rear. When loaded, those things had no more than three inches of freeboard, so you had to be constantly mindful of your center of gravity, a lesson Ed learned the hard way. The first time he stepped into his boat, he lost his balance and over-corrected. The canoe tipped sideways, instantly filled with water, and sank straight to the bottom; it was still tied to a piling, so recovery was simple enough, but Ed was mortified–and soaked all the way to his waist. If he’d done something like that in the main channel, it would have been a disaster.

Each of the boats had a local guy to do the paddling. I can’t remember how much we paid them, but they definitely earned it. There were many stretches where they were barely making any headway, paddling against the current, as well as sections where shallow water or encroaching vegetation made paddling impractical, so each of the guys had to balance precariously in the prow of his canoe, and they shoved the boats forward with long poles. Progress was so slow we didn’t even make it to our destination the first day. The boats pulled over to the bank, and I was more than a little surprised to see a house built in the trees, at least ten feet off the ground.

We were greeted by a couple standing on an elevated wrap-around porch, three or four kids peeking out the open windows of the tree house, their eyes as wide as dinner plates. Their dazzled expressions left no doubt that we were the strangest sight they’d ever seen. Our paddlers and the tree dwellers were already acquainted; everyone in the area seemed to know everyone else, but it wouldn’t have mattered if we were all total strangers. In remote locations like that, at least in those days, travelers were welcomed as a matter of course, and the fact that we were able to pay a little something for their hospitality made us honored guests. We stayed the night in hammocks, wrapped in mosquito netting. I don’t recall the experience being nearly as terrible as it had been in Puerto Lopez. It could have been that I was getting used to the jungle noises, or maybe I just felt safer, sleeping in a tree house, ten feet off the ground.

The next morning, we were off at first light, poling and paddling up the narrow waterway. It wasn’t obvious from our perspective, because all we could see from the river were trees and more trees, but we were approaching the jungle-clad foothills of the Cordillera Occidental, the western slopes of the westernmost range of the Colombian Andes. The area we were about to enter was, at that time, one of the least explored regions in all of South America. After about three hours, we arrived in San Francisco, but seriously, the only resemblance to the City by the Bay was the name. It was pretty much as Kent described, four ramshackle houses on stilts that put them at least eight feet off the ground. Considering all the rain we’d already encountered, it was hard for me to imagine this place getting even wetter. I didn’t want to be around to see the kind of flooding all those folks were so obviously prepared for.

The entire population of twelve turned out to greet us. In truth, they’d been waiting for us, because the news about the gringos headed in their direction had traveled faster than our canoes. El Manco was easy to spot. The term “Manco” is usually an insult, a reference to something defective, or, more precisely, to a one-armed man. This guy had embraced his defining handicap, a right arm that had been severed above the elbow, and that wasn’t even his only problem. He was also missing his right eye, nothing there but an empty socket and an ugly knot of scar tissue. “Tough old bird” doesn’t begin to describe a hardscrabble character like Manco; he had a face with creases like a roadmap straight to his own personal version of hell. Jaime asked for him by name, so he stepped forward, scanning the lot of us very suspiciously with his one good eye.

Jaime handed him the note, explaining that it was from Kent Vance. At the mere mention of Kent’s name, the whole bunch of them broke out in wide smiles. Several of the men had been cradling shotguns, and all the barrels dropped, simultaneously. Kent was obviously a popular guy in those parts, and any news from him had to be good news. Manco handled the piece of paper gingerly, like some precious, fragile thing, and labored his way through the note, reading the words aloud for everyone to hear. It was a simple enough proposal: Kent was asking him to guide us to the “Quebrada de los Indios,” the place where he’d found the artifacts; leave us there for a few days, and then return to guide us back out. Jaime explained that we would also need lodging, and porters, and transportation back to Puerto Lopez when we were finished. With all of that, there was going to be a payday for every man in the whole tiny town, and once that became clear, we were instant celebrities.

It was already too late in the day to start out, so we unloaded our gear from the canoes, then hauled it up the steps into one of the stilt houses. We spent a pleasant afternoon hanging out with our hosts, who were genuinely thrilled to have us. They had a good thing going out there, mostly thanks to our friend Kent. He’d been gone almost half a year, but the claim he’d abandoned was still producing, even without the dredge, and they were able to pan enough gold out of that stream to provide them all a steady income. That was important, because they were supposed to be living off the land by growing crops, and that wasn’t nearly as easy. Homesteaders had to work a piece of land, make a go of it, stick it out for five years, and only then did they get legal title to it. In Lopez, that was a problem, because it was too wet there for farming. Every time the rivers rose, unpredictably, and at least twice a year, their fields washed away, and they had to start over. There in San Francisco, they got along by raising chickens and pigs, growing small plots of vegetables and bananas, some hunting and fishing, and every few months, they bought supplies in Puerto Lopez, using gold dust for currency.

They had a highly innovative communal outhouse, which was up on stilts, with a square of tin for a roof, but open to the breeze, with a waist-high screen around the throne for privacy. Ed was having stomach trouble and badly needed to use it, so shortly after we arrived, he excused himself and started up the ladder. By the time he hit the third step, we all heard a loud squealing noise, and watched as a half dozen pigs came running. Ed, who was clearly on an urgent mission, kept climbing into the enclosure and took a seat, while the pigs gathered into a bunch underneath the structure, all of them staring upward in anticipation. What happened next was epic, but I’d best leave the details to your imagination.

Bright and early the next morning, we started out in canoes, but we hadn’t gone far before we had to abandon them and continue on foot. Manco was out front, and we had him and three other men from the settlement carrying our equipment and supplies using old-fashioned tumplines, rope slings with straps across their foreheads to help support the weight. I felt like a pampered b’wana on safari, watching our porters sweating and puffing, with me carrying nothing but a machete, but I’ll tell you: even with nothing for a load, us gringos were hard-pressed to keep up with those guys.

There was no real trail here. We followed the contours of the land, climbing ravines, hacking our way across ridges, Manco swinging a razor-sharp machete with his single powerful arm as he led the way, up into the foothills. There were several stretches where we had to walk in the fast-flowing creeks because the vegetation along the banks was impenetrable. It was a bit slippery, stepping on loose rocks under the water, but otherwise not too bad, until the bottom dropped away and the water got deeper, rising to our knees, then to our waists. We roped ourselves together before entering a pool where the water came up all the way to our armpits, then everyone half-trudged, half-swam along in single file following Manco, who was unstoppable. The porters held their loads above their heads to keep our stuff at least halfway dry, and it was a challenge for everyone, to avoid getting swept off our feet by the current.

At one point, back on solid ground again, Manco’s route led across the face of a cliff at the top of a ravine. It seemed there had been a major derrumbe, a landslide, since the last time anyone came this way. There actually had been a trail in this particular spot; Manco had blazed it himself, cutting a ledge of sorts into the cliff face, but most of his work had been erased when the mountainside crumbled. Backtracking to find another way would cost too much time, so the Colombians elected to forge ahead, and Manco went first, to ensure it was even possible. He faced the muddy cliff, bracing himself with his one good arm and his stump. Then he inched sideways, crablike, his bare feet seeking purchase, until he reached the other side. He stopped then, and beckoned for the rest of us to follow.

The Colombians negotiated this challenge calmly and efficiently. They rigged some ropes tied to stout trees to ferry our gear across. The porters themselves went next, and then my friends. I went last, with my heart pounding in my chest. I don’t do that well with heights, and this was at least an eighty foot drop, with rocks down below. Any injury here would be a disaster, days from even the most basic medical care, and that thought compounded my little height phobia to the point that I very nearly froze. Swallowing hard, I tightened the laces on my soaking wet hiking boots, took a deep breath, and did the crab thing, never looking down. I’m sure it didn’t take more than a minute, but it seemed like an hour before I finally ended up with the rest of the group on the other side of the ravine, relief washing over me in a palpable wave. It occurred to me that we were all going to have to do this maneuver again on our way back out–but that was a worry for another day.

After about six hours of steady trekking, we came to a clearing beside the stream, and Manco called a halt. The other men unshouldered their loads, dumping everything into the middle of the open space, and then broke out some food they’d brought along, taking a much needed break before starting back. Paul and I plopped down onto some mossy boulders beside the stream, glad to be off our feet, while Ed went looking for a tree, and Manco conferred with Jaime and Gustavo. We were on a tight schedule, because we had to be back in Puerto Lopez in seven days. It would take us one day of trekking just to get back to San Francisco, then another day in the canoes to the river port, traveling with the current this time. That meant we could camp here for a total of five days, no more than that. Hopefully, that would be long enough to locate the flat-topped hill, and do a preliminary survey, to see if it was really a burial mound.

I took a good look around, and saw nothing but trees, and vines, and walls of tangled vegetation in every direction. “How does he know this is the right place?” I whispered to Paul.

Jaime overheard the question, and took the liberty of answering. “A clearing in this jungle does not create itself,” he said. “Manco made this one, because he has used this spot as a camp. He tells me there are signs here.”

“Signs? What does he mean by signs?”

“Carvings. On those boulders.”

I stood, and took a closer look at the damp stone I’d been using for a chair. There were indentations right where I’d been sitting, mostly hidden by the spongy layer of moss. Paul took out the Buck knife that he always carried on his belt and skinned off the greenery, revealing a pattern of curving lines carved into the surface of the stone. Another boulder had a series of dimples, all in a row. There was a figure like a bow tie, or an infinity symbol, and yet another that featured an animal, like a monkey, a primordial stone monkey. This was no casual graffiti. Without metal tools, it would have taken weeks, if not months to carve such deep lines into granite boulders, so whoever did it must have been living here, or very near here.

Manco and the others left us then, because they wanted to get home before dark; Manco made a solemn promise to return for us in five days, and we had no choice but to trust him. We were literally putting our lives in his hands, because I don’t think there was any way any of us could have found our way back out of there without Manco or his neighbors to guide us. We made quite a project out of levelling the clearing, tossing aside all the stones and branches and other debris, sending lord knows how many thousands of bugs scurrying, hopping, and slithering in every direction. Then we set up our tent, which was going to be our only shelter for most of a week, making sure to keep it as far away and as high above the banks of the creek as possible. Right on cue, rain started falling, so we all crowded inside, rolling out sleeping pads and bags, figuring out how we were going to make it work, all of us sleeping, as well as staying out of the weather in such confined quarters.

The rain stopped about mid-afternoon, so we set off walking up the creek, to see what we could see. I busied myself checking every boulder of any size for more carvings, and I found a few. I’d finally unpacked my cameras, and I was taking some photos when I heard Paul shouting, just up ahead. He’d found a huge boulder jutting into the stream, and this one looked like it had a face carved into the top of it, almost like a figurehead on the prow of a ship. Thick moss covered the entire surface of the stone, and before I could snap a single picture, the other guys started peeling it off, revealing an extraordinary assortment of patterns and symbols. Spirals, a coiled snake, more monkeys. We checked the other side, where the moss was even thicker, and peeled it back to find what amounted to a prehistoric mural, an interlocking pattern of deeply carved symbols and triangular faces, covering the entire upper surface of the boulder.

This was not my area of expertise. Aside from the spirals, which are common to many cultures, I’d never seen any reference to symbols quite like those, and I knew of no existing research that might explain them. For all we knew, there were even more carved boulders in the area, but even if there were not, these were quite a find. The symbols were well executed, the spirals all but perfectly symmetrical, and the patient effort required to create something like that had to have been extraordinary.

We did a good job cleaning off the big boulder, and I shot most of a roll of slides, as well as some black and white film, making a record of the symbols. What else were we going to find out there? The excitement was ramping up, the whole bunch of us feeling a touch of gold fever, when a weather front rolled down from the mountains, and a heavy rain started falling. We made it back to the shelter of our tent, and holed up there for the rest of the day, making our dinner out of cold beef stew eaten straight out of the can, congealed grease and all. The stuff actually tasted pretty good, the way I remember it; and we were all far too beat to be even the least kind of finicky.

Rain fell all night, on and off, so none of us slept well, if we slept at all. Every hour or so, somebody would crawl out of the tent with a flashlight, and trudge through the rain and the mud to the banks of the creek, to make sure it wasn’t rising to a dangerous level. According to Jaime, the rain falling on us directly wasn’t that much of a threat. The real danger was miles away, higher in the mountains, where there might be much bigger storms sending serious water our way, with very little warning. Our camp was not on stilts, or anchored in the trees, so we were vulnerable to even the slightest amount of flooding.

The next morning was cool and surprisingly clear, so we were able to get our propane stove going to heat filtered water for coffee. Gustavo whipped up a big pot of oatmeal, enough to feed the lot of us, and we sat around on those carved up boulders having a pleasant breakfast. I’d changed out of the wet jeans I’d been wearing, but there was nothing I could do about my boots, which were doomed to stay soaked until we left that place.

Paul took charge for this next phase, not because he was best qualified, but because none of the rest of us was willing to challenge him. We set off upstream, pausing at the big boulder so that I could take a few pictures in the sunlight. Then we pushed on, walking along the bank when we could, otherwise in the water, which was relatively shallow here. We came to a hill, a steep upslope on the right side of the creek. From the bottom, it was impossible to tell if it was flat on the top, or if it was devoid of trees, so Paul and Gustavo climbed it. That was no easy proposition, requiring extensive hacking with their machetes, and a lot of sliding backwards on the slippery slope. They finally reached the top, only to find it was a perfectly ordinary hill, no different from any other, with exactly the same sorts of trees.

They came back down, and our party continued upstream, checking out two more hills, one on the left, which Paul climbed by himself, the other rising up on the right bank, with Ed and Gustavo taking point. We could hear them talking after they crested the formation, which was smallish, as hills go; only about fifty feet tall. I couldn’t make out what they were saying, but Ed sounded pretty excited, and he shouted down for the rest of us to join them. With vines for handholds and exposed roots for footholds, this little hill was quite an easy climb so we were all up top in no time at all. It wasn’t what I’d call flat up there, not really flat, but it was quasi-level, and there was an open space, maybe 100 square meters, with no tall trees. It was almost like a clearing in the jungle, but on the top of a hill. Had it been cleared by people, a slash and burn field for growing corn or whatever, but on a flat hilltop, above the level of the floods? That was a possibility, but who would have done it, and when? Was there another explanation, something to do with the nature of the rock, or the depth of the soil? How about a crazy storm with a microburst strong enough to denude a hilltop? Regardless of how the clearing came to be, the hill fit the basic description provided by Kent Vance. Flat on the top, no tall trees, upstream from Manco’s glory hole. Paul walked out to the middle of the clearing and stood there looking around, with his hands on his hips. “This is where we dig,” he announced, stamping his foot on the thick mat of vegetation. “Let’s get the shovels!”

The morning sun had given way to a solid overcast that grew darker as we trudged back to camp, everyone’s boots making comical squishing noises as we walked. We almost made it before the storm broke, but in this case, almost wasn’t nearly good enough. When the rain started falling, it fell in sheets, like a squall at sea, so by the time we clambered into the tent, we were all soaked to the skin–again! There was nothing to do at that point but sit and wait, frustrated, dripping, and more than a little impatient. Rain fell relentlessly all the rest of that day and most of the night. I don’t think any of us slept worth a damn in that tent, not at any point in the trip, but that second night was definitely the worst. We kept up the hourly watch on the level of the creek, which was churned up to a roaring, muddy froth, and it WAS starting to rise; just not to an alarming depth. Not yet.

The second morning wasn’t nearly as pleasant as the first. The rain had cut back to a drizzle, and the level of the creek dropped closer to normal, but there was so much mud everywhere, it was like camping in a bog. Paul saw no reason to let the weather slow us down any further, so he laced up his wet boots, and shouldered a pick. “I’m going,” he announced. “Any of you ladies coming with me?”

So off we went, like the seven dwarves minus two, hi-ho, hi-ho-ing our way to the treasure mine, carrying all of our digging tools. The hike upstream was almost becoming familiar. We passed the big boulder and the other carved stones, then came the hill on the right, and the other hill on the left, until we finally reached that more-or-less flat-topped hill we’d come to investigate. From the bottom, there was nothing out of the ordinary. We spent some time examining the banks of the creek where it flowed past the base of what appeared to be an unremarkable natural hill, looking for something, anything that might point to treasures here. There were no caves, no pockets, no bones, and no pottery or carved stones sticking out of the mud.

We all clambered up the hill then, hauling picks and shovels, machetes, and a digging bar. The drizzle turned into steadily falling rain, but we weren’t going to be deterred that easily; after everything we’d been through to get to that spot, by god we were going to dig! The clearing, if you could really call it that, did not expose any soil. Instead, there was a layer of tangled, intertwining roots and vines at least six inches thick that covered the whole open space like a carpet. Paul picked a spot right in the middle, and used a pick axe to hack through it, chopping a straight furrow about six feet long, and then he cut two more lines at right angles to the first, making three sides of a square. Gustavo used the digging bar and a spade to pry and chop roots underneath the thick mat of vegetation while the rest of us rolled it up like a rug, revealing a six foot by six foot patch of red clay. We attacked that exposed section with our shovels, only to find that the soil on that hilltop was hard as a brick. Paul swung a pick using all his considerable strength, and barely left a dent. Jaime was clearly disappointed. A burial mound will always show evidence of prior digging, loose soil with intermingled layers, and that was clearly not the case here. Paul picked a few more spots, took a few more solid swings with that pick, but all he was doing was rattling his own teeth.

“Since we’re here,” I said, “there’s one more thing we should try.” That’s when I broke out the metal detector for the first time, handling it very carefully, because it was still raining pretty hard. There were delicate electronics in the handle that had to be shielded from moisture. The case was sealed, but it wasn’t waterproof, and I’d been warned when I bought it about the importance of keeping that part of the device protected from the weather. I had the box wrapped in so many layers of plastic that I could scarcely read the dials, but I got it going, using the standard twelve inch sensor at the end of a four-foot pole, and I scanned all around the square hole we’d created. There were no pings that might indicate metal, so I scanned again, very slowly. Still nothing. Gustavo took a coin from his pocket and asked me to turn around while he hid it; an impromptu test, to make sure the detector was capable of functioning in such a soggy environment. I averted my eyes, then turned back around, and walked forward, sweeping the dish in a wide arc until I heard a telltale beep. From that, I found the hidden coin almost immediately, proving to everyone–including myself–that the device was working correctly.

I tried walking across our clearing from north to south, and then from east to west, without so much as a wiggle on the dial, meaning only that there was no metal within range. I removed the standard twelve-inch dish and hooked up the big sensor, the hula hoop, which Ed had been carrying for me. I had to change several settings on the box, no easy feat, the way I had it wrapped up. To really do it properly required a bit of fine tuning and recalibration after you swapped sensors, but the rain was falling even harder now, so that definitely wasn’t happening. I held the machine with both hands, keeping the hoop parallel with the soggy ground and about 18 inches above it, then I swung it from side to side as I walked slowly across the clearing. The nominal maximum range for that hoop sensor was 10 meters, and at that depth it was supposed to reliably detect larger metal objects, like engine blocks, ore bodies, or burials filled with gold!

I turned the detector off and on a few times to make sure the batteries were still good, then I crisscrossed the clearing again, without so much as a blip. That’s when the rain started falling hard enough to be a threat, so we packed everything up, climbed back down to the creek, and barely made it back to the tent when the clouds burst for real. The creek had long since settled down from the night before, but now the water was starting to churn again, and we talked about that. Considering the incredible volume of water that scoured that creek bed on a regular basis, it was beginning to seem less and less likely that the artifacts Manco panned from the stream came from close by. The fish hooks, especially, were no doubt lost one at a time in many different places, only to end up in the same pocket of gravel. They could have come from anywhere along the course of that stream or its tributaries; gold is heavy, and it will definitely travel down a slope. The petroglyphs were another matter. They were created right here, in this very spot, but we had no way of knowing if the people who made the petroglyphs had any connection to the gold.

The rain stopped in the afternoon, stopped completely, but it was too late to go up the creek again. We used the time to rinse out muddy clothes, and Gustavo got the propane stove going, fixing us all some coffee and a big pot of canned stew, with some extra canned vegetables tossed in to bulk it up. That was the best meal we’d had in days, and very much appreciated. Paul broke out a pint of Scotch that he’d brought along and shared it around, everyone swigging straight out of the bottle. By the time the sun went down, heading into that third night, we were in quite the mellow mood.

On our third full day out there, we took advantage of a break in the weather to fully explore the area around our camp, looking for more carved boulders, or anything else left behind by the people who did the carving. I used the metal detector to scan the banks of the stream, especially around the boulders, but once again, there was no metal to detect. Shortly before mid-day we heard a shouted greeting, and we were surprised to see Manco walking up the creek toward us with a pack on his back, carrying a shotgun. Gustavo offered him some coffee, so he set his things down and took a cup, eyeing our tent with obvious curiosity. He explained that he was hunting nearby, and figured he should stop and see how we were getting along, and to bring us some extra supplies. He gave Gustavo a small sack of fresh produce: potatoes, a couple of onions, and some yucca. That was certainly a welcome addition to our larder. We were down to nothing but canned sardines, and I hated canned sardines!

Manco opened his pack, and pulled out a large tin can filled with the biggest surprise of all. They had just put on a feast back in San Francisco, to celebrate the unexpected windfall that our little expedition brought to them. They killed two chickens and slaughtered a pig, then they prepared some wonderful food. Everyone contributed, and Manco himself had cooked up his specialty, salchicha de cerdo, home-made pork sausage. I peeked in the can, and saw a greyish coil of uncooked intestine, tied off in sections, stuffed full of god knows what, since these people wasted nothing when they slaughtered livestock. We all made the connection at about the same time, visualizing those squealing porkers that came running when anyone used the outhouse. Ed went positively green, and came within a hair’s breadth of losing his breakfast.

Manco wanted to know if we’d found more gold, and seemed surprised when we said we had not. We quizzed him about the petroglyphs, wanting to know if there were more in the area. He wasn’t aware of any others, but he’d actually never been any further upstream than the place we were standing. It was apparent from our conversations with them that the people who lived in that jungle were a superstitious bunch. Manco himself, tough as any man I’ve ever met, was actually very leery of the petroglyphs. He’d never peeled off any moss to better expose the carvings, and never went off looking for more of them, because he saw them as what might best be described as bad juju. They were placed there by “Los Indios,” the Indians, and he was taught in the mission school that the Indians worshipped devils. What we did with the carvings was our business, but for his own purposes, he had never seen any point in poking at that sort of thing.

He accompanied us around the bend to that biggest boulder, which he clearly had NOT seen before. The multitude of carvings that we had exposed, especially on the back side of the stone, made him visibly uncomfortable, and he turned away, reluctant to even look at them. Was it possible that we scored a first when we peeled the moss from that boulder? Were we the first men from the modern era to lay eyes on that obviously ancient artwork? That might well have been true, but the sense of discovery would have been much more complete, if we hadn’t been led to this spot by a map drawn on a cocktail napkin.

Back at the camp, Manco inspected our tent close up, amazed that five full-grown men could fit in that tiny space, much less shelter from the weather inside it. He examined the trenches Paul dug to channel rainwater away from the corners, nodding his approval. He told us that the rain over the last few days was heavier than usual, and advised us to keep an eye on the water level in the creek–exactly as we’d been doing–and to seek higher ground if it overflowed its banks. There was one more thing, almost an aside as he was walking away. There was a tigre roaming in the area, a jaguar. He’d seen tracks and signs of a fresh kill just that morning, and he could tell it was a big one. “If any of you have to leave your little canvas house at night,” he warned, “never go out alone. Always go two by two, and be sure to make a lot of noise.”

Ceramic Jaguar mask from the Tumaco culture, circa 300 B.C

That was a sobering thought. Up to that point we’d been lucky, but the fact was, we were in an incredibly dangerous area, facing off against everything from killer floods to river pirates, and now we were surrounded by deadly wildlife? Earlier that day, Gustavo came across an eight-foot long fer-de-lance, one of the world’s most poisonous snakes, not ten yards from our camp. He dispatched it with a well-placed shot to the head, then used his machete to decapitate the creature, a commonly employed precaution, before throwing the remains in the creek. “The cuatro narices kill more Colombians than anything else in the jungle,” he explained, “because they’re not afraid of us. If I hadn’t shot him first, he would have found his way into our tent tonight!”

And then there was the deadly food! Manco’s generous gift of his special sausage, made from the odd bits of a pig that had been fattened on feces, was, by unanimous vote, left off of our menu that night. We dined on canned sardines and boiled potatoes instead, very glad to have them, and right after dinner, Gustavo dug a hole and buried the sausages, right next to our latrine. I was insanely nervous after we put out the lantern, imagining deadly snakes with every rustle of the canvas, and I was certain that I heard something huffing around outside. It wasn’t raining, for a welcome change, so there was no need to make that hourly check on the level of the creek, and we made it all the way through until daybreak without anyone leaving the tent. Paul and Ed were stretched out closest to the door, so they were first outside, and I heard Ed let out a low whistle. The rest of us crowded out through the zippered opening to find the two of them crouched over a big footprint in the mud, directly in front the tent.

The track was fresh, and the only animal in that jungle big enough to make such a mark was the jaguar we’d been warned about. Ed and Gustavo walked back to the latrine area, and we heard excited shouting. There was a freshly dug hole next to our toilet trench, edged with deep claw marks. Manco’s sausages had been disinterred, and they were gone, gobbled, down to the last greasy morsel.

The weather finally cooperated that day, our last full day in the camp, and we explored up the creek for a considerable distance. There were no more carvings, no more clearings, no more hills that looked anything other than natural, so after three or four miles, we turned around, and worked our way back down. On the way back to camp we climbed old flat-top one last time, and found that the square opening we’d cut through the vegetation was already growing back together. We talked it over, and couldn’t see much point in doing any more digging on the top of that hill. In my view, the lack of trees was a natural phenomenon, due to the lack of any real soil up there. That hard red clay by itself was poor in nutrients, and wouldn’t support the growth of large trees. The tangled carpet of roots and vines spreading across the open space had somehow adapted to this environment, but with the intense daily rainfall, every scrap of leaf litter washed away downhill before it could accumulate and decompose. Larger plants, like trees, just never got started.

We had two unsolved mysteries, which we discussed at length while sitting around our camp. First, who carved the petroglyphs? How old were they, and what did they signify? Second, what was the actual source of the gold artifacts that Manco panned from the creek? According to Jaime, the whole Pacific coastal region was lousy with gold. There were gold mines in Barbacoas, directly south of us, that had been worked since the days of the Conquistadores, and there were gold dredging operations in the Choco, north of Buenaventura, that were one of the mainstays of the regional economy. There was gold in its natural form right there in the stream that ran past our camp. The ancients in Tumaco, not so far from where we were, knew how to harvest the raw metal from the rivers and streams, and they used it to create some of the most extraordinary golden treasures in the ancient Americas. They might well have been responsible for the gold artifacts that Manco found here, but it was impossible to determine how and where those artifacts first entered the water. Jaime did NOT think the Tumacans had any connection to the petroglyphs, because they were not known for stone carving, and their art was far more sophisticated than these crude stone monkeys.

“So who do you think carved the petroglyphs?” I asked.

Jaime shrugged. “I have no idea, and to be honest, I don’t really care. I’m an art dealer, not an archaeologist. At the end of the day, the thing that’s most important, with all of these ancient cultures of Colombia, is their art. The contribution that they made to the history of humanity through the unique qualities of their finest artistic expression. I’ve never understood why you archaeologists are so obsessed with the mundane. What does it matter how the people lived, or how they made their pottery, or what kind of trash they buried?”

We argued that point, because I was of the opinion that a societies’ trash is far more reflective of their humanity than their art–and even though I can’t claim to be an archaeologist, the science of archaeology tends to agree with me. I also felt that the petroglyphs were extremely important, and that they were quite probably very old, though I had no way of proving my assumption. As for what they signified? All I could really do was take my best guess. Deeply carved petroglyphs like these were a permanent mark on the landscape, and the only thing I could imagine that would inspire so much dedicated effort was religion. The large boulder in particular may have been a shrine, or a monument. The spirals may have represented an origin myth, the monkeys and the snake may have been clan totems, or mythical entities. There must have been a village near this petroglyph site, which we dubbed, somewhat pretentiously, the Vale of the Stone Monkeys. Were the petroglyphs created all at once, in the course of a single lifetime, or were they done over the course of a much longer time period, with successive generations adding to the original? The big boulder might be a map, or a mural, or a boundary marker. Lord only knew–it might even be–(steady, steady–wait for it–) art!

Not finding any gold was a disappointment, but we couldn’t say we didn’t give it our best shot. Having the metal detector was a huge advantage, almost like x-ray vision. We tested the device any number of times using metal of various kinds, including a gold wedding ring, buried at varying depths. The detector was infallible at finding all the metal that we planted to test it, no matter how well hidden, so I had a high level of confidence that there simply was no other metal, not in the places we examined. Could we have missed our target? Turned back too soon, climbed the wrong hill, failed to notice something important? Yes, perhaps, of course, and obviously, but there was a limit to what we could do, especially with limited time, in one of the rainiest jungles on the planet.

Rain fell most of that last night, but it was a relatively gentle, purposeful rain, just enough to keep the jaguars at bay, and all the clouds cleared out by morning. We took a little time packing up the camp, and we’d no sooner finished when Manco and his buddies came walking up the creek, hailing us as they approached. They had obviously started out from San Francisco very early, and traveled at warp speed without the burden of five clumsy gringos and all our fancy equipment. Their packs were going to be lighter for the return trip, since we’d eaten up all the food, buried all of our trash, and left behind the heavy picks and shovels, which we no longer needed.

We took a poll that morning, to see how each of us felt about coming back, better prepared, and taking another shot at locating the source of the gold artifacts. The only vote for a return visit came from my buddy Paul, who was absolutely convinced that there were more treasures up that creek. He’d seen those gold fish hooks with his own eyes. We were standing in the place where they were found, and we were surrounded by ancient carvings that weren’t on anyone’s map. If that wasn’t a recipe for a golden bonanza, it was, at the very least, an excellent premise for a Hollywood movie. Whenever Paul got something into his head, he was like a hound dog hot on a scent, and he was NOT content to be leaving a previously unknown archaeological site with nothing to show for it but pictures of petroglyphs. Jaime, for his part, had seen enough, and Gustavo’s opinion, of necessity, mirrored that of his boss. Ed was quite ready to head back to any place with normal toilets, and me? I would have gladly traded all my worldly possessions for a hot shower, a cold beer, and a dry pair of socks.

I took a last look around the Vale of the Stone Monkeys, easily the most exotic place I’ve ever explored, and I really did have to wonder who those people were, and what their story might have been. Pretty good odds, that’s one of those questions that will never have a good answer. Our trek back out was a breeze, walking downhill, and downstream, nobody carrying all that much weight. Manco even found an alternative to that dicey route across the face of the cliff; a little longer, by his estimate, but it was definitely safer. I’d been dreading that cliff for the whole of the past week, so when I found out we didn’t have to go there, it was like a weight lifted off my chest, so much so that I was almost able to enjoy myself along that final stretch. The diversity of the plant life was simply extraordinary; gigantic examples of unique exotic species, all of it growing in such profusion it was hard to tell which was where, and I could only imagine the insects, birds, frogs and what-have-yous that had never so much as been catalogued. I was reveling in all of that as we walked along, until, in what seemed like no time at all, we reached the place where they’d left their canoes, and paddled the rest of the way to San Francisco in grand style.

Compared to our tent in the jungle, that little community on stilts seemed positively civilized, a safe haven carved out of an eminently hostile rain forest, with an emphasis on rain! We spent a very comfortable afternoon and evening there, out of the weather, safe from floods, snakes, and hungry Jaguars. We had a quite decent dinner of fresh caught fish, along with vegetables from Manco’s garden, than we all slept like babes, wrapped in netted hammocks, outside on the porch of the elevated structure. The next day, our friends took us all the way to Puerto Lopez in their dugouts, another relatively quick trip, traveling in the same direction as the river most of the way, so we moved much faster, and no overnight stop was required. The river port, which had seemed so incredibly poor and primitive when we first saw it the week before, looked like a bustling metropolis when compared to the little hamlet of San Francisco. There were so many buildings, so many people, and they even had electricity, so my wish for a cold beer came true, just like that.

Ivan was already there and waiting for us, so after one last overnight stay in Puerto Lopez, the last leg of the return journey went off without a hitch. We had a wet but otherwise uneventful journey up the swampy coastline, finally arriving at the dock in Buenaventura. We were all soaked to the skin from rain and salt spray, our clothing caked stiff with mud; we hadn’t shaved or had a proper bath in nearly two weeks, but none of us wanted to stop just to clean up. Jaime retrieved his Land Rover and drove us to Cali, an 80 mile trip that took more than three hours on curvy mountain roads; heavy truck traffic coming to and from the port left us with no doubt that we were out of the jungle, and back in civilization.

Jaime dropped us off at the Intercontinental Hotel, which was quite new at the time, and at the high end of the scale. They took one look at us and sneered, insisting they had no rooms available. Paul slapped a $100 bill on the desk, the equivalent of $2,000 Colombian Pesos, and we ended up renting their best suite. We sent our filthy clothes to be laundered, we each had a proper bath, and we ordered an elegant dinner from room service, including a pricey bottle of Paul’s favorite Scotch. The way we were acting, you’d think we’d really found a treasure out there in that jungle. As I remember it? We were feeling about as lucky as three guys could possibly be, just to have gotten out of there alive.

I provided a report of our expedition, along with photos of the petroglyphs, to my faculty advisor at the Universidad de Los Andes, and she shared the information with the research department of the Colombian National Museum. I didn’t use any of it for my thesis; I went a different direction with that project (see Tairona Gold: the Rape of Bahia Concha), so there was never any follow-up on my end. I’m sure the report I provided to the authorities was dutifully noted and filed away, but I seriously doubt if it was ever acted upon, and it’s unlikely that there has ever been any officially sanctioned scientific study of the petroglyphs in the Vale of the Stone Monkeys. Let’s just say there are plenty of other unexcavated archaeological sites in Colombia that are significantly easier to get to.

In the fifty years that have passed since the expedition took place, quite a lot has changed in that part of the world, but very few of those changes have been for the better. Colombia’s lengthy war with the FARC guerrillas hit this region particularly hard, and it has yet to recover. Today, nearly all of southwestern Colombia, from Cali south to the border with Ecuador, including the whole of the Pacific Coast, has devolved into a lawless territory controlled by the drug cartels; the whole area is considered extremely dangerous, for travelers and researchers alike. Tragically, that situation isn’t likely to get better any time soon. (See my recent post, Tumaco: Part 1: Atrocity Trumps Antiquity on the Coast of Colombia). Meanwhile? Those stone monkeys are watching, and they’re waiting. For what, I really couldn’t say.

~~~~~

In case you were wondering: this tale is true, and all of the events described actually happened (I don’t think I could have made this stuff up). Some of the names were changed, though most of the principal characters, who were all older than me, have long since passed away. The story was woven together from scraps of memory and journal entries that date back more than half a century; I did my best to smooth it into a good read. Some of the photos, most notably the pictures of Buenaventura and Puerto Lopez, were borrowed from the Internet, while the photographs of the petroglyphs are my original work, and are exclusive to this web site; to the best of my knowledge, no other photographer has ever visited the Vale of the Stone Monkeys.

Disclaimer: I am not an academic. The assumptions made and the conclusions drawn in these posts are those of a reasonably well-informed enthusiast; I haven’t put in the work that might make me an expert. At one time, I was up to my neck in this stuff (or at least, up to my armpits), but the most that entitles me to is an opinion.

Unless otherwise noted, all of the images on this site are my original work and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

MORE SOUTH AMERICAN ADVENTURES:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

Long Ago and Far Away: South America in the Early 1970's

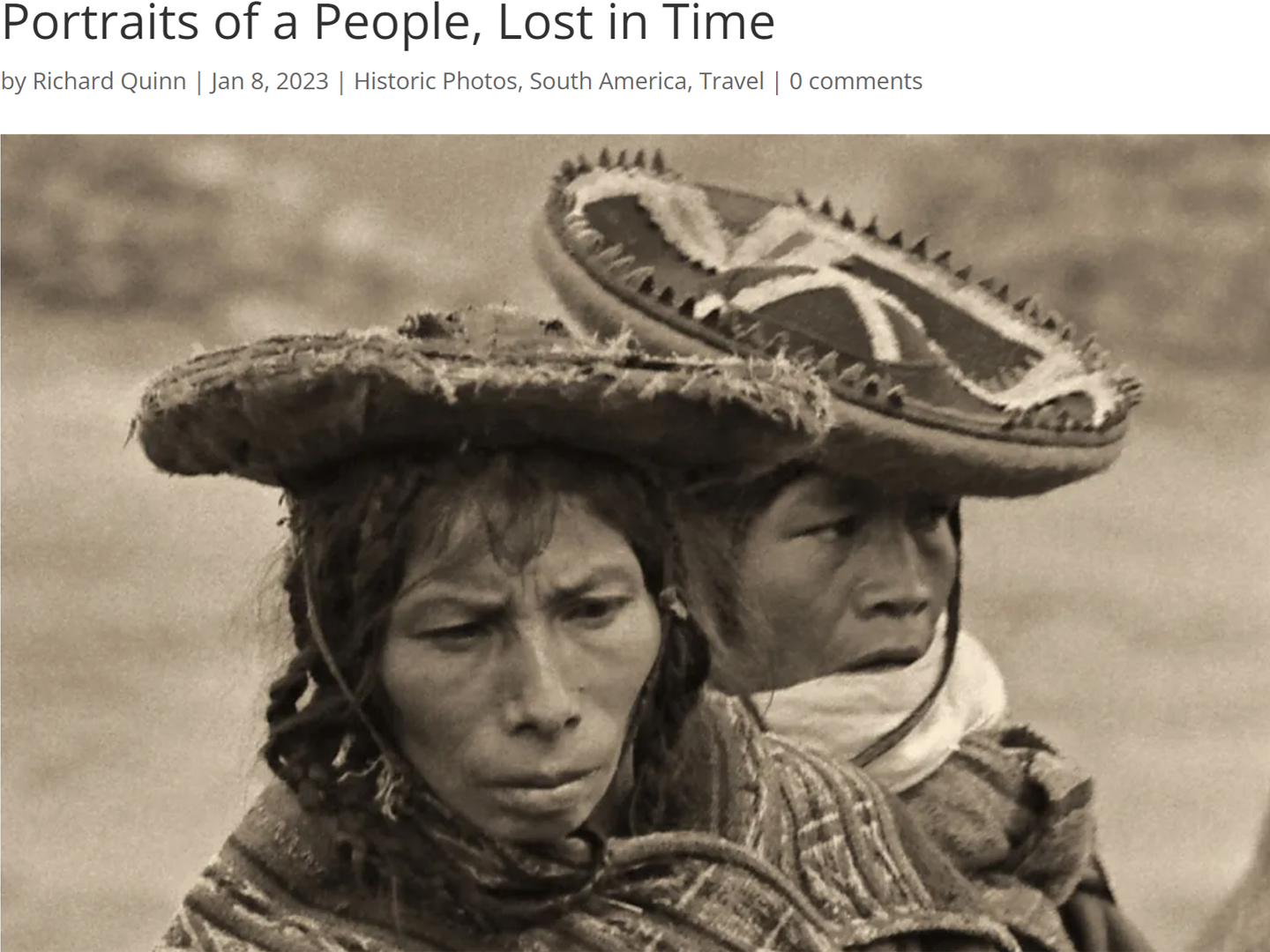

Portraits of a People, Lost in Time

50 year old portraits of Andean natives in their traditional dress, taken in mountain villages not yet tainted by outside influences.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Puno Day Festival

Historic photos of Peru's Puno Day festival, taken in 1971. Included is the reenactment of the birth of the Inca empire on the shore of Lake Titicaca, with costumed dancers lining the streets of Puno.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

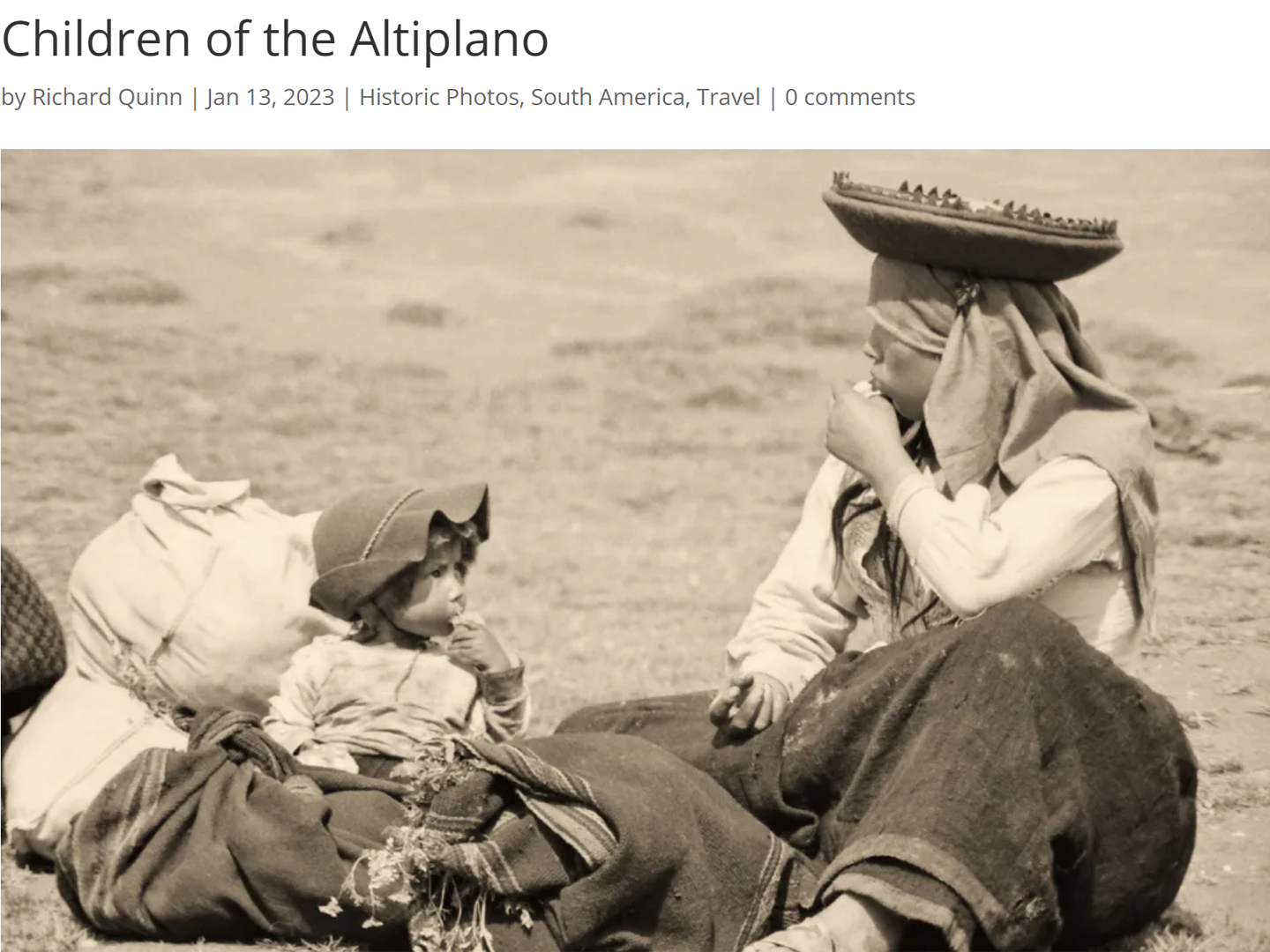

Chinchero: The Place Where Rainbows are Born

Candid portraits of villagers in traditional dress, taken in Chinchero, Peru in 1971, before the outside world intruded.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

An Overabundance of Bowlers: A Brief History of Headgear on the High Plateau

Andean natives have adapted to the intensity of the high altitude sun by taking a very simple precaution: everyone, almost without exception, wears a hat when they venture outdoors.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tairona Gold: The Rape of Bahia Concha

It was the Tairona gold that triggered a blood lust in the Spanish invaders, ultimately causing the destruction of the entire Tairona civilization. That cycle was repeated in modern times, when the lust for Tairona gold infected the guaqueros, causing the destruction of the last refuge of the Tairona ancestors, in one final humiliation, one last indignity: the RAPE of Bahia Concha!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent

Paul dug with his hands then, finally sticking his arm into a hollow space, pulling out a dark object. Grinning at me from the bottom of his hole, he handed up what he’d found. A round blackware vessel representing a coiled serpent, open in the middle, with a spout at the top of the head. I’d seen a lot of Tairona artifacts, but I’d never seen anything remotely like that one.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

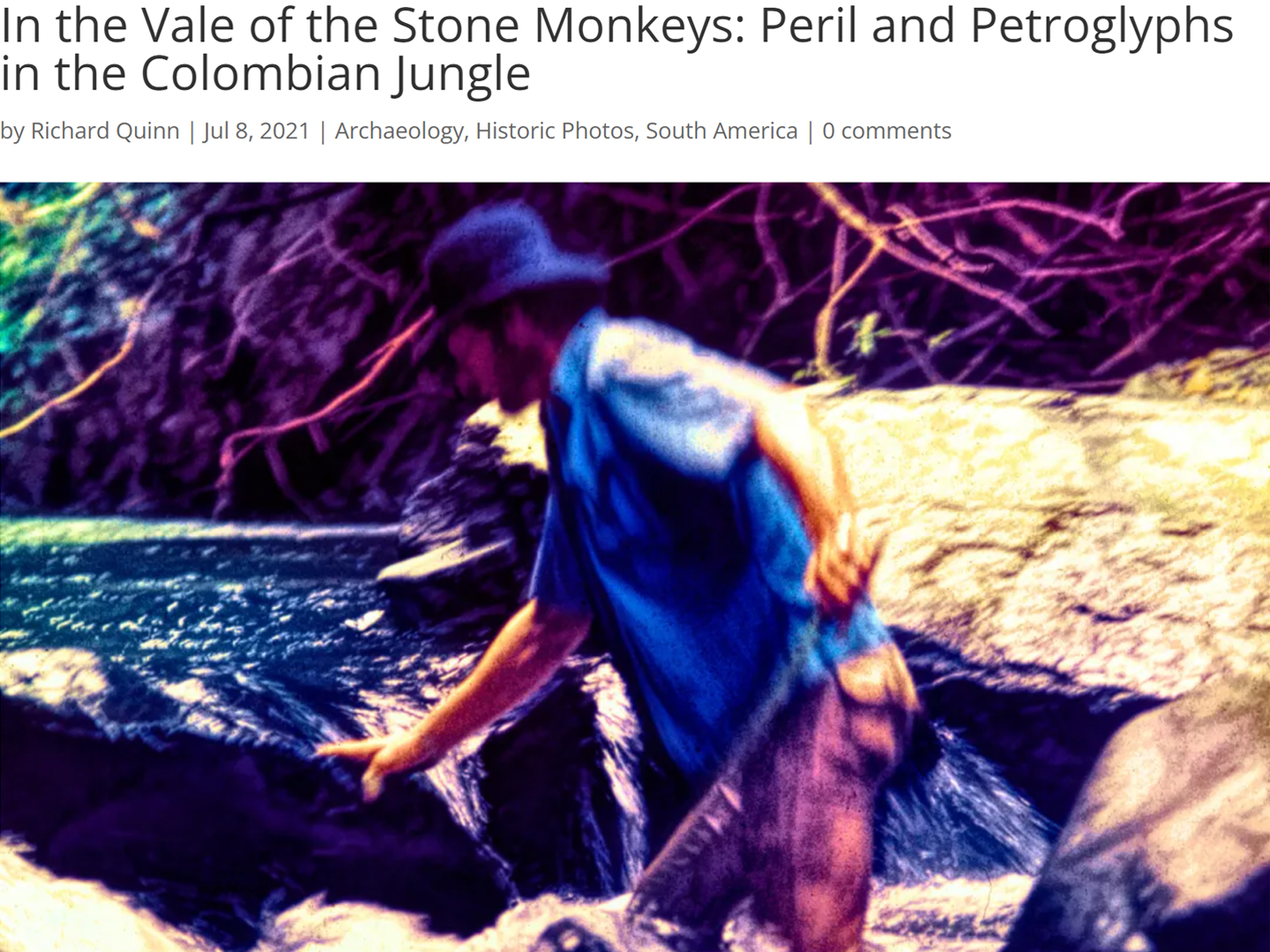

In the Vale of the Stone Monkeys: Peril and Petroglyphs in the Colombian Jungle

El Manco was easy to spot; he had embraced his defining handicap, a right arm that had been severed above the elbow, and that wasn’t even his only problem. He was also missing his right eye, nothing there but an empty socket and an ugly knot of scar tissue. “Tough old bird” doesn’t begin to describe a hardscrabble character like Manco; he had a face with creases like a roadmap straight to his own personal version of hell.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

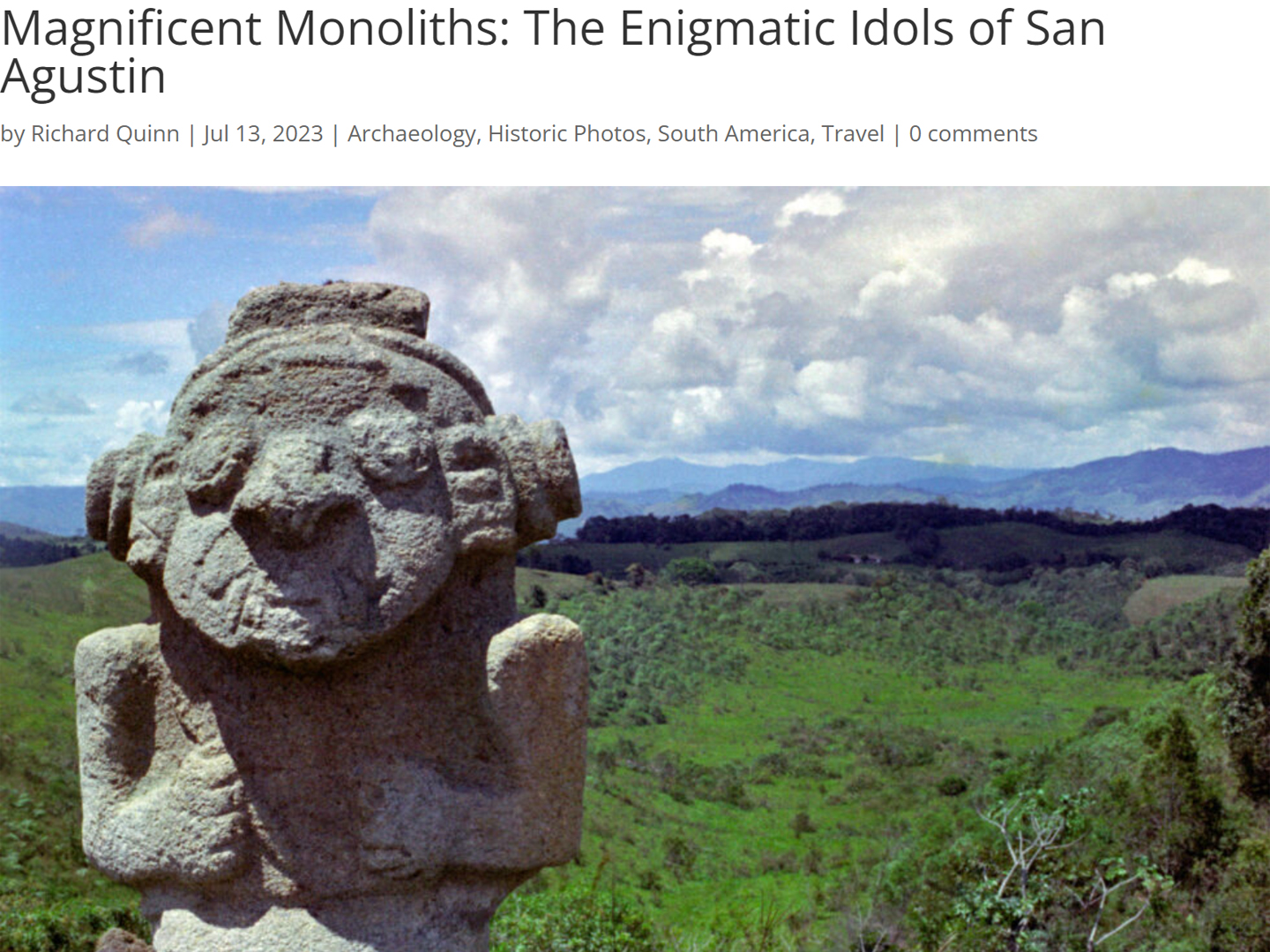

Magnificent Monoliths: The Enigmatic Idols of San Agustin

At least 200 monolithic statues are preserved within the boundaries of the San Agustin Archaeological Park, along with 20 monumental burial mounds. Each statue is unique, but taken as a group they provide a fascinating overview of the rituals and beliefs of one of the earliest complex societies in the Americas. The enigmatic idols of San Agustin are truly unmatched among the world’s ancient monuments.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments