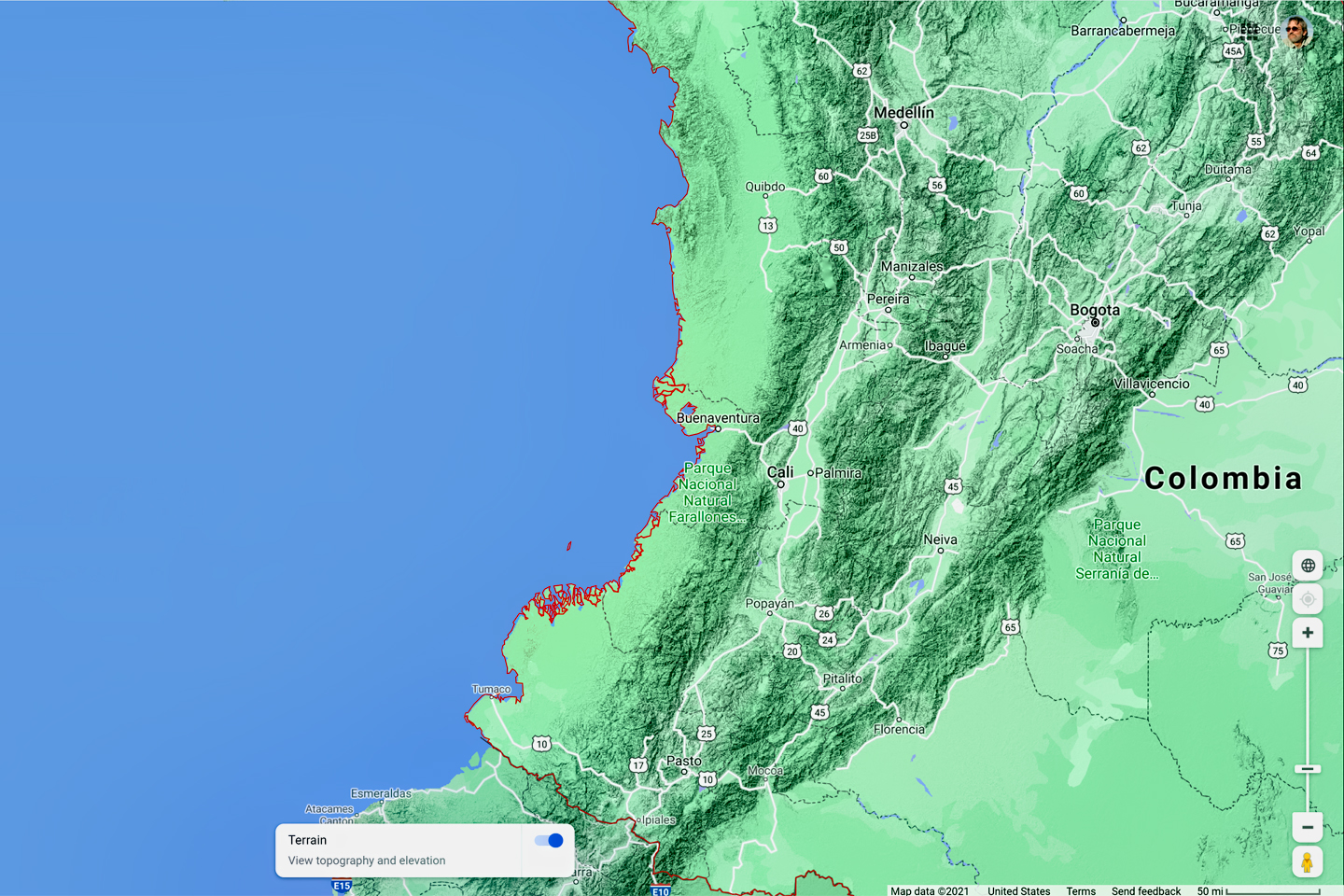

Colombia is the only country on the South American Continent that touches both the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans. The northern, Atlantic coast is considered a part of the Caribbean, and it’s much as you might expect: white sand beaches and palm trees, an azure sea, beautiful sunsets, a unique, laid-back lifestyle. There are world-class resorts catering to international travelers, and a lively port, Cartagena, where cruise ships are welcomed all year around.

The western, Pacific Coast is another story altogether. Through a quirk of geography, that coast features one of the wildest, wettest jungles on the entire planet, an impenetrable tropical forest that lies trapped between the steeply rising Andes Mountains and the sea. This is a sparsely populated territory threaded by countless rivers and streams, and there are few settlements of any size, because there is little flat land that isn’t in a continual state of flood from the incessant rain. Saltwater marshes and mangrove swamps line much of the coastline, completing a trifecta of inhospitability; at least, from the perspective of people. Strange plants, stranger bugs, snakes, and other creatures seem to like it just fine, because the area, as a whole, is one of the most biodiverse regions on earth. Several Colombian National Parks have been established to protect unique ecosystems, but they’re not the kind of parks that welcome crowds of visitors. There aren’t any roads, for one thing, which makes travel in the area difficult, expensive, and potentially quite hazardous.

The only real city on the Pacific Coast is the port of Buenaventura, which has long been considered one of the worst destinations in Colombia for tourists. There’s a terrible crime problem, a terrible climate, and extreme poverty, such that the vast majority of the city’s 400,000 residents live in slums, lacking clean water and basic sanitation. The place does have its charms, most notably a vibrant Afro-Colombian culture with a unique cuisine and a contagious joie de vivre. Food lovers had begun to take notice, inspiring something of a renaissance for the beleaguered municipality, but in 2020, all gains were reversed. The Coronavirus pandemic hit the place hard, pushing the unemployment rate to more than 75%, leaving a lot of people hungry, and more than a bit desperate. According to recent news reports (February, 2021), drug gangs have gained control of much of the city, and local law enforcement is losing its grip on the rest. If you don’t have business at the port, or a need to catch a boat to travel north or south through the swamps, it’s best to steer clear of Buenaventura.

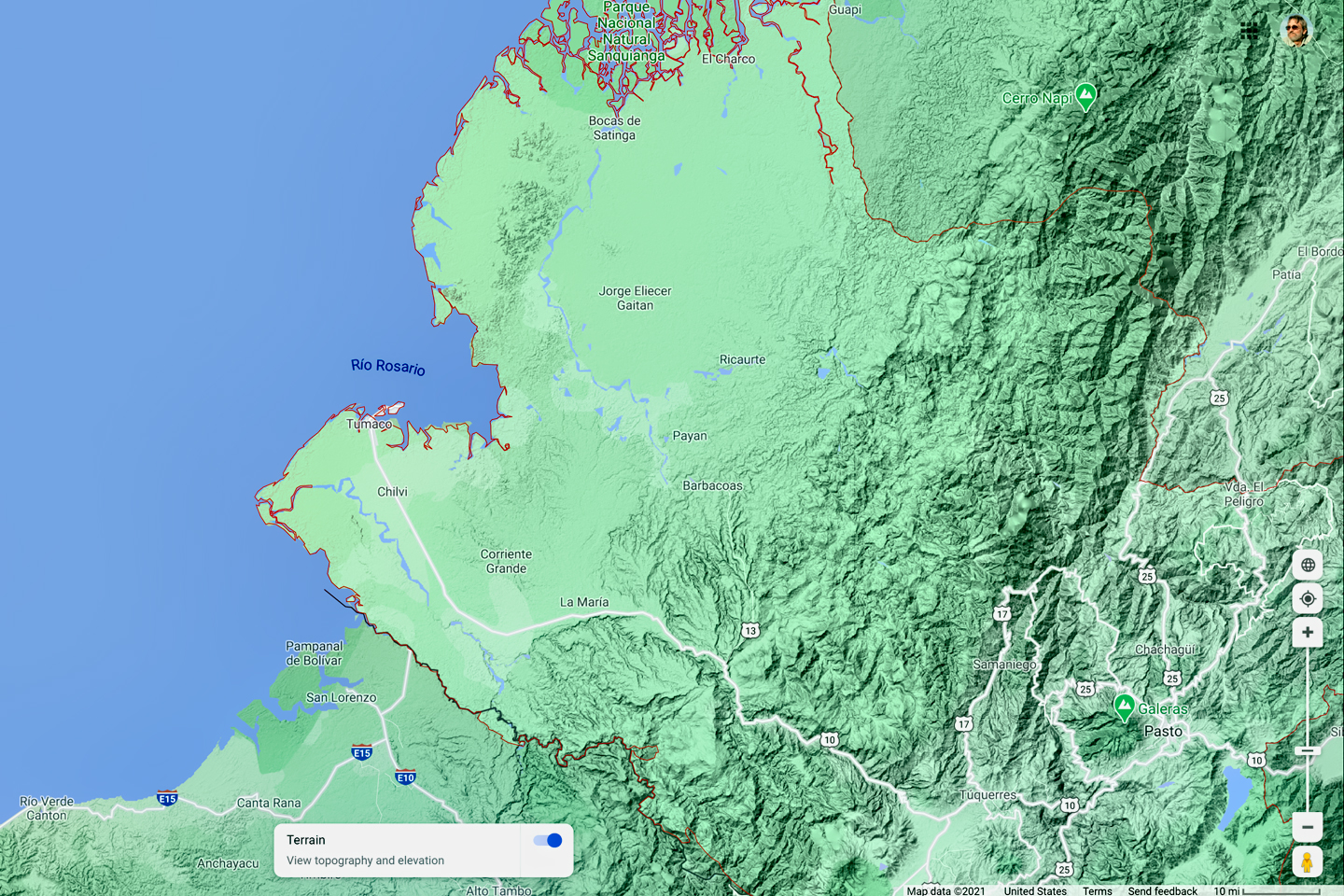

The only other town of any size on that coast is Tumaco, situated further south, near the border with Ecuador. In recent years, the once sleepy port has gained a dubious reputation as ground zero in Colombia’s notorious cocaine trade. With the assistance of the FARC guerrillas, the drug cartels took over the surrounding province of Nariño, and turned it into a lawless territory that has become the world’s largest producer of the world’s most dangerous drug. Coca leaf is the primary crop on thousands of regional farms in an area larger than the state of Massachusetts. In Nariño, pasta, raw cocaine base, is weighed out like gold dust and serves as currency, with a value that’s probably more stable than that of the Colombian Peso. Floating laboratories known as cristalizaderos are hidden under cover in the mangrove swamps, where they’re safe from aerial surveillance, and their output is measured by the metric ton. All of the finished product moves through Tumaco, where it’s loaded aboard ships, planes, and even submarines, destined for markets in the US and Europe. The booming business has expanded all the way to Buenaventura, some 200 miles north, for the simple reason that the docks of the larger city can accommodate larger vessels. Illicit cargo moves between the two ports on small boats that ply the manglares, the maze of coastal mangroves. Buenaventura is bad, Tumaco is even worse, and the region that lies inland, between the swamps and the mountains, is the no man’s land of the Cauca Jungle, a very dangerous blank on the map.

Hiking in the Cauca jungle, circa 1972

I traveled there myself, long before the drug lords took over, tracking down clues that might have shed some light on an archaeological mystery. There was also a tantalizing possibility of gold and glory–but of course I didn’t find any of that, and rather than resolve any mysteries, I simply added more questions to the stack. (For more on that adventure, check out the final post in this series, In the Vale of the Stone Monkeys: Peril and Petroglyphs in the Colombian Jungle).

TUMACO: CERAMIC ARTISTS FROM BEFORE THE TIME OF CHRIST

Sixty years ago, in the mid-twentieth century, Tumaco gained fame for another reason, as the focal point of an entirely different shady enterprise. In the 1960’s, a pipeline was built to carry crude from newly discovered oil fields in the jungles of the Putumayo, up and over the great range of the Andes to tankers waiting offshore at Tumaco. This Trans-Andean pipeline was an enormous project that provided a major boost to the regional economy. As the area around Tumaco was developed, settlers moving in to the area encountered a multitude of low hills rising from the alluvial plain, north and east of the Rio Mira. When they dug into that landscape to plant their crops and build new roads, they plowed open a window into an ancient, mysterious past.

Most of those hills, as it turned out, were just like the mounds that had been discovered several decades earlier, on the nearby island of La Tola, just across the border in Ecuador. They weren’t natural formations, they were funerary mounds, and they were loaded with artifacts buried there by an all but forgotten people. In Colombia, they simply call them the Tumacos, after the name of the port, and across the border in Ecuador, the La Tolitas, after the island where they first discovered the mounds. In recent years, researchers coined the term Tulato, a contraction of the two, as an inclusive reference to all of the ancients who farmed and fished and built a vibrant civilization along this coast, back in the days when Rome was busy becoming an Empire.

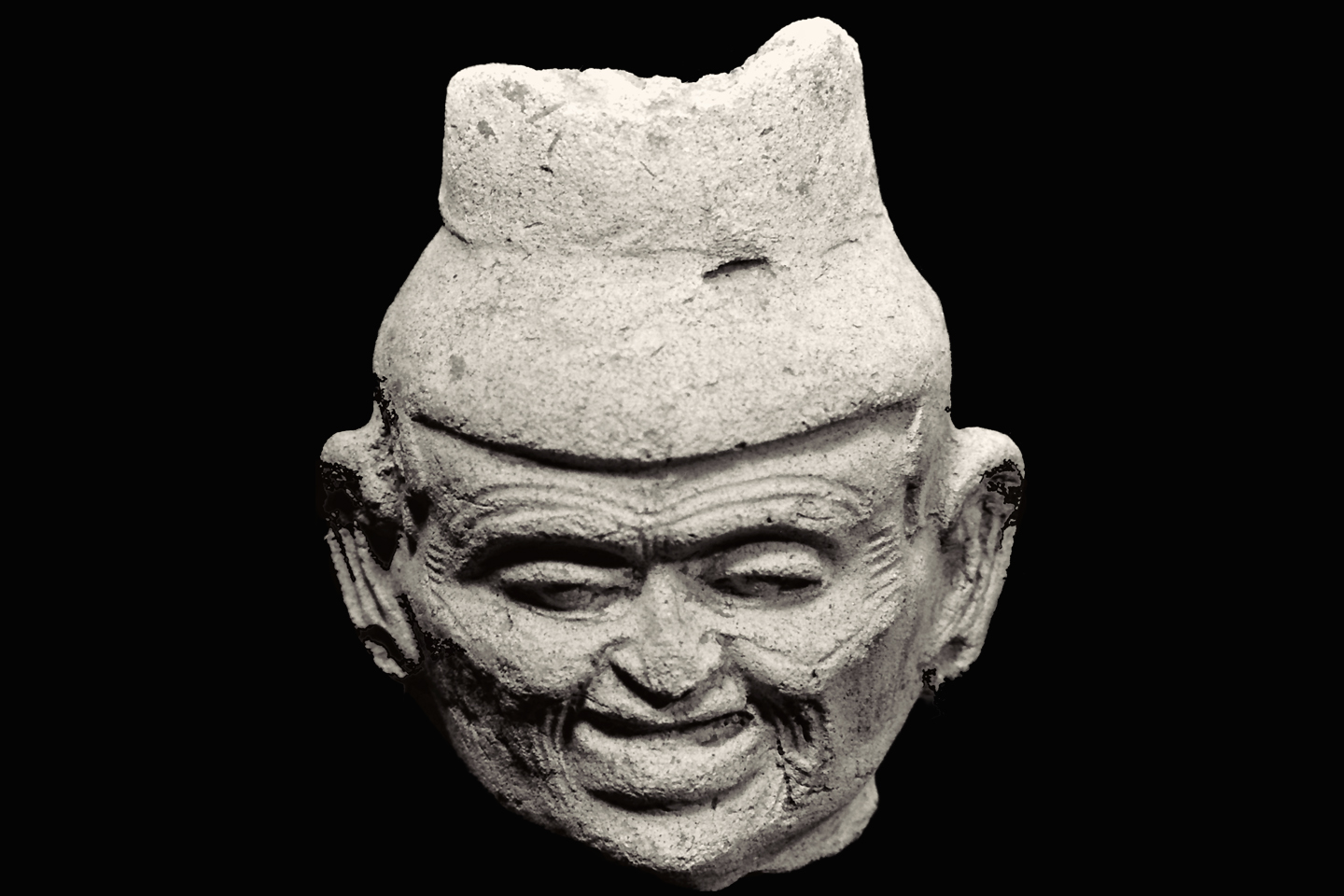

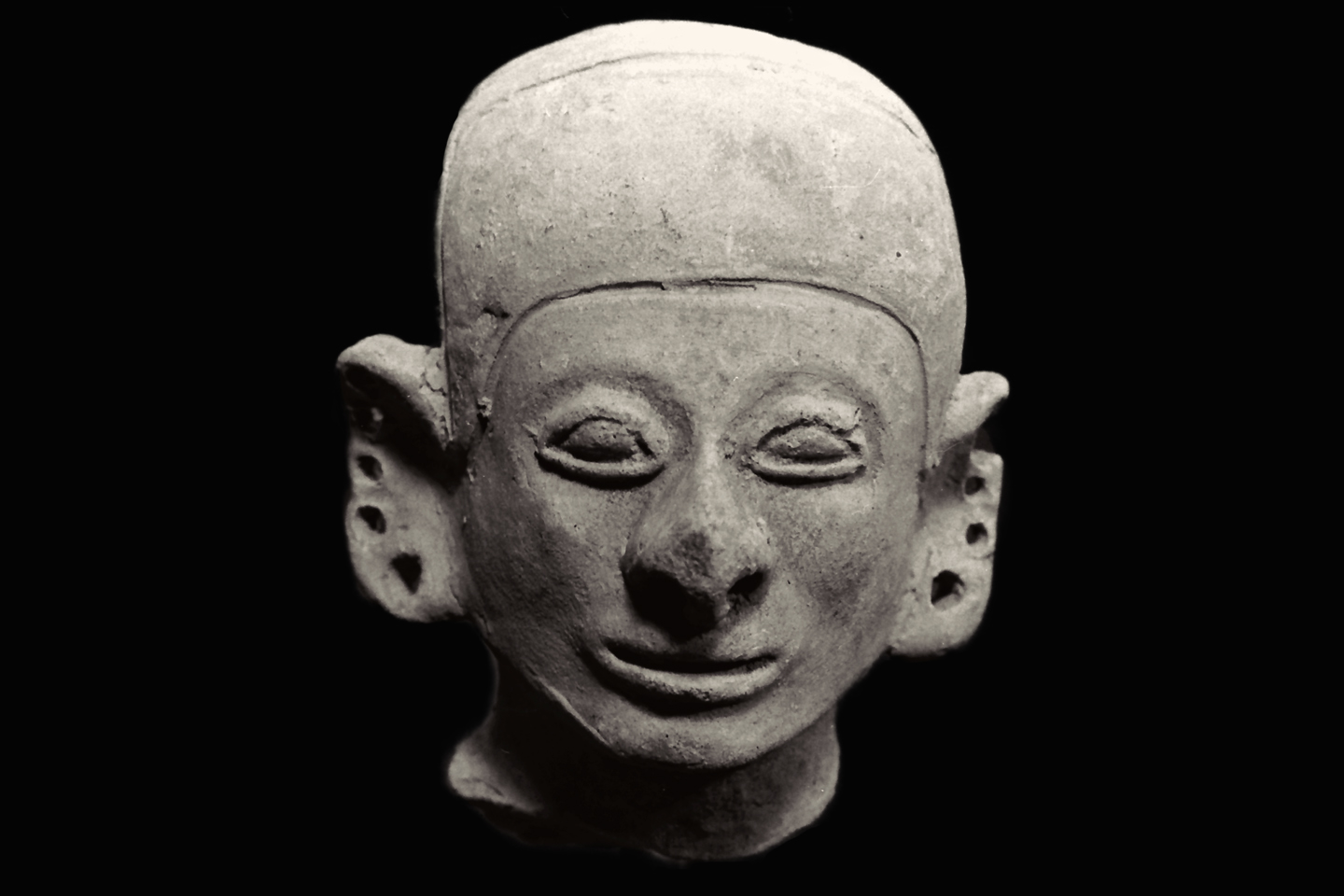

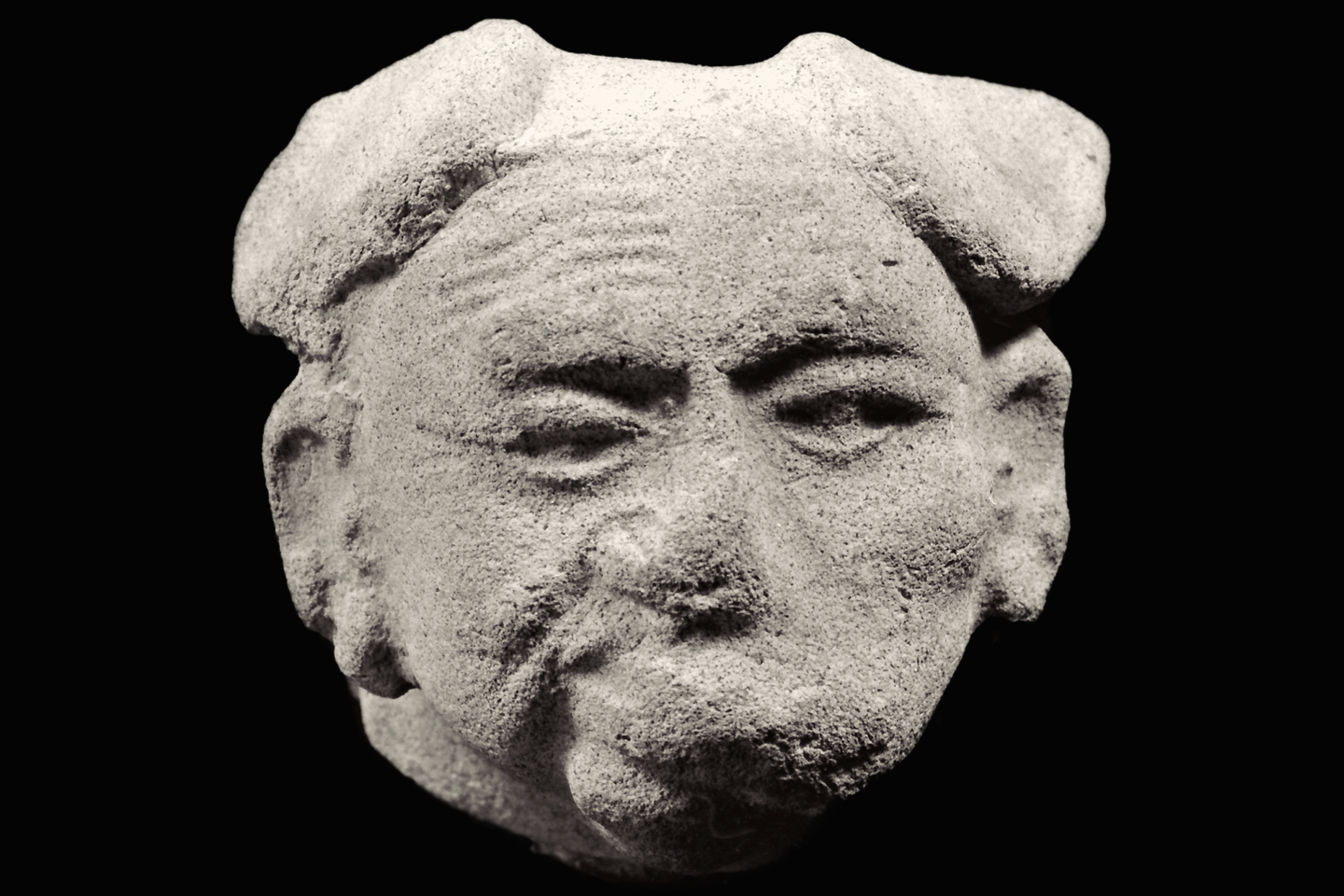

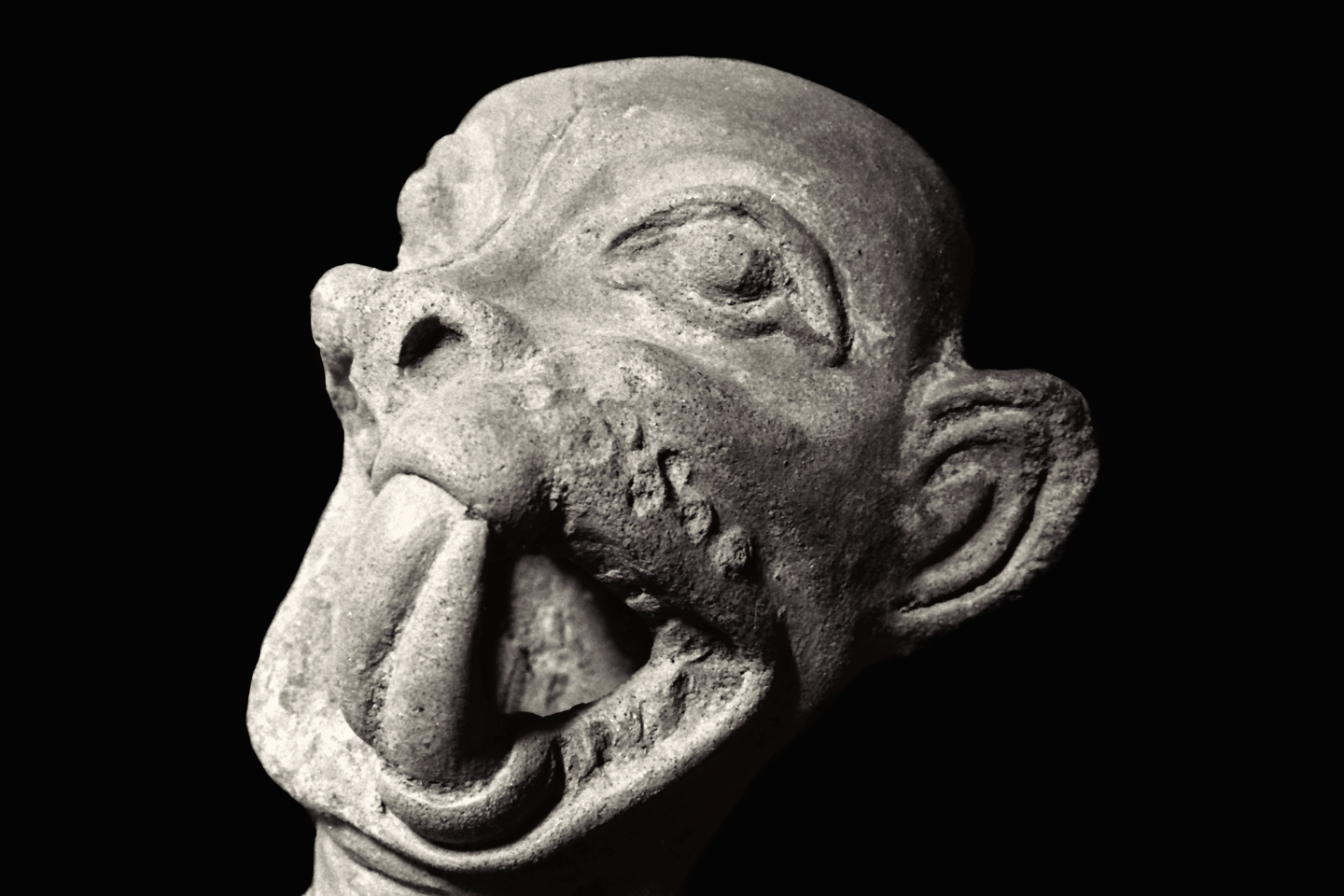

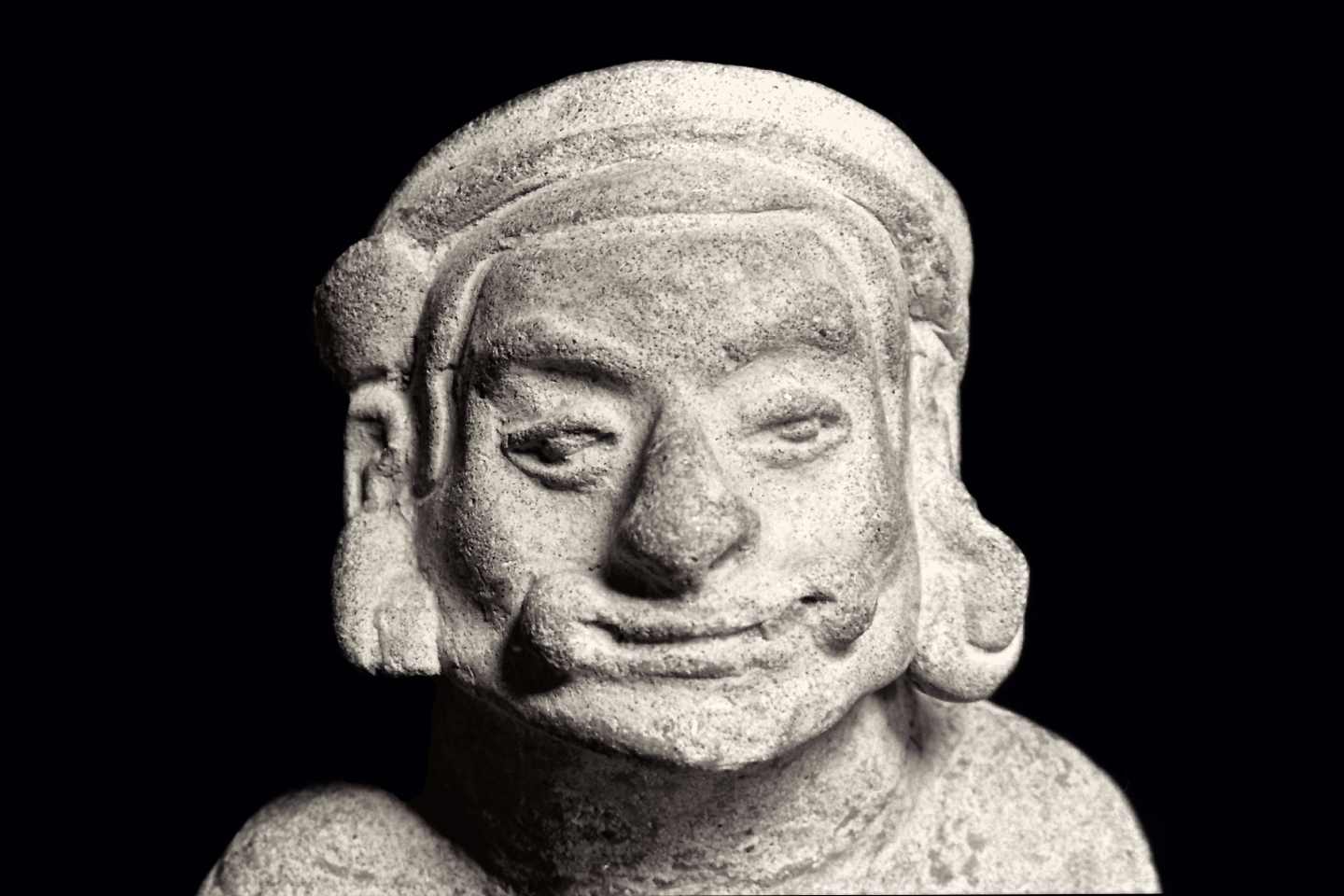

Whatever name you use, the Tumacos either died out or left the area long, long ago, but they didn’t exactly disappear without a trace. They left behind an extraordinary record of their daily lives and their animistic mythology in the form of ceramic figurines, ranging from a few inches to two feet or more in height. Many are intact, though most are in fragments, found in layers of shards that were entombed in those burial mounds, known locally as tolas. Other mounds in the area were housing platforms, built to raise Tumaco dwellings above the level of seasonal floods, and some of the larger earthworks quite likely supported temple complexes. More pottery was buried beneath the housing and temple platforms, and fragments were everywhere, scattered throughout the general area.

Once the artifacts were exposed, the word got out, attracting legions of guaqueros, treasure hunting tomb robbers. The primary interest for those guys was the gold and platinum jewelry found in many of the burials; personal adornments such as nose rings and ear rings, along with small gold sculptures, golden masks, and other ceremonial objects that had been worked with considerable skill. The gold was an easy sale on the open market, not for its historical value, not even for its value as primitive art. No—the value of those priceless artifacts was determined primarily by the weight of the gold each piece contained, as if that was all that mattered.

Within a matter of a few years, every readily accessible tola on either side of the border had been gutted and stripped of artifacts. The guaqueros sold most of their finds to middlemen in Tumaco, who shipped them off to their partners in Cali or Bogota, and from there, they entered the main stream of the antiquities market. Most were quietly purchased by private collectors, not just in Colombia, but also in Europe, the U.S., and Asia. There were laws in Ecuador prohibiting trade in ancient artifacts, but until the mid-1980’s, there was no such law in Colombia, so the Tumaco heritage, extraordinary in its complexity, was scattered to the four winds.

The slide show below features a random assortment of Tumaco figurines and fragments. Click any photo to expand the images to full screen.

MOLD MADE: AN ANCIENT FIGURINE FACTORY

Tumaco artisans fashioned their figurines by first making a three dimensional carving, presumably in wood. Once the carving was complete, they would create a mold from the front side of it using moist clay that was formed around the carving, dried, carefully separated, and then fired in a primitive kiln. Once the molds were hardened, they were used to produce ceramic copies of the original carving; copies which were finished in various ways, painted, and fired in their turn. The purpose of the figurines, the ways in which they may have been used, is open to speculation.

Press-molded figurines of this nature are not exclusive to the Tumaco culture. Other ancient peoples along the coasts of both Ecuador and Peru utilized the technique, as did the ancient Maya in Central America, all in the same approximate period of time, give or take a few hundred years. One very good question: who came up with it first? And what was the mechanism for sharing this knowledge, particularly among people as spread out geographically as the Maya and the Tumacos?

Pictured below is an original ceramic mold from Tumaco, representing a human figure, missing the legs and feet, but otherwise intact. An impression was taken using modeling clay. The resulting figurine is a bare-chested male, devoid of any ornamentation.

It’s interesting to note that most of the figurines recovered in the Tumaco area are broken, and in many cases, it appears as though they were smashed deliberately before they were buried.

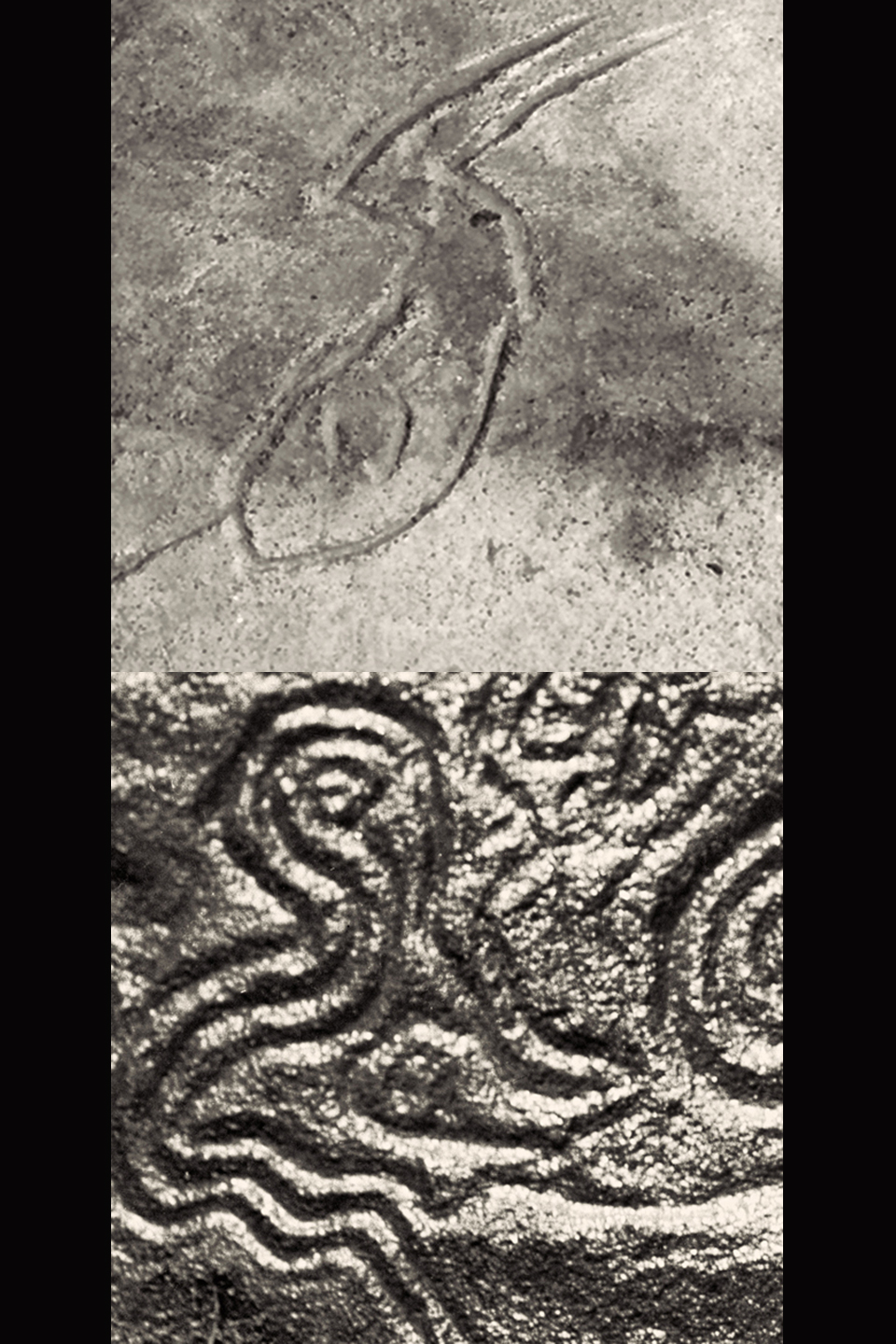

Below, another original mold from Tumaco, and a corresponding impression in modeling clay. This one creates a demonic creature with the body of a man and the head of a jaguar, with a cat’s eyes and whiskers, a belted tunic, and long hair in braids.

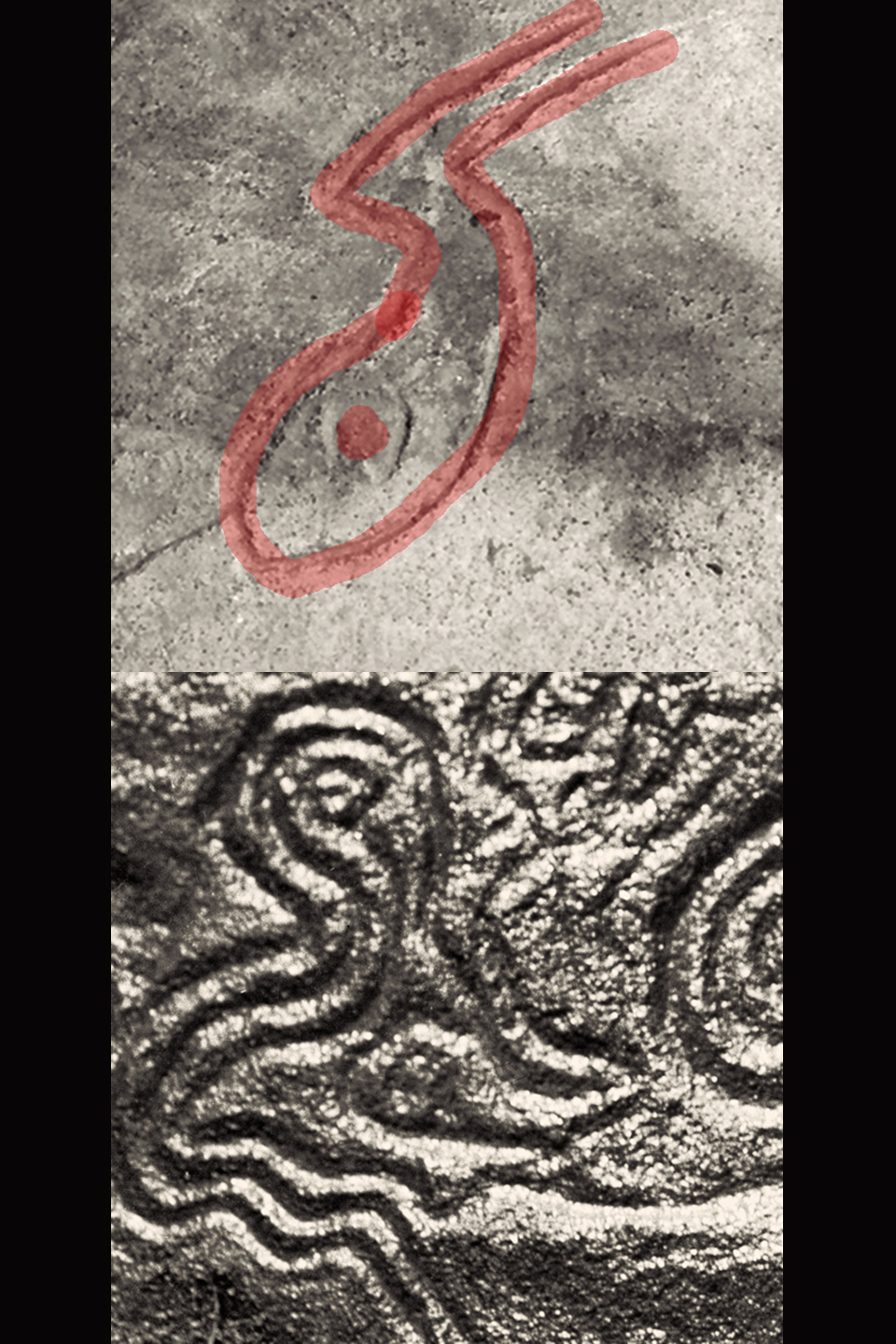

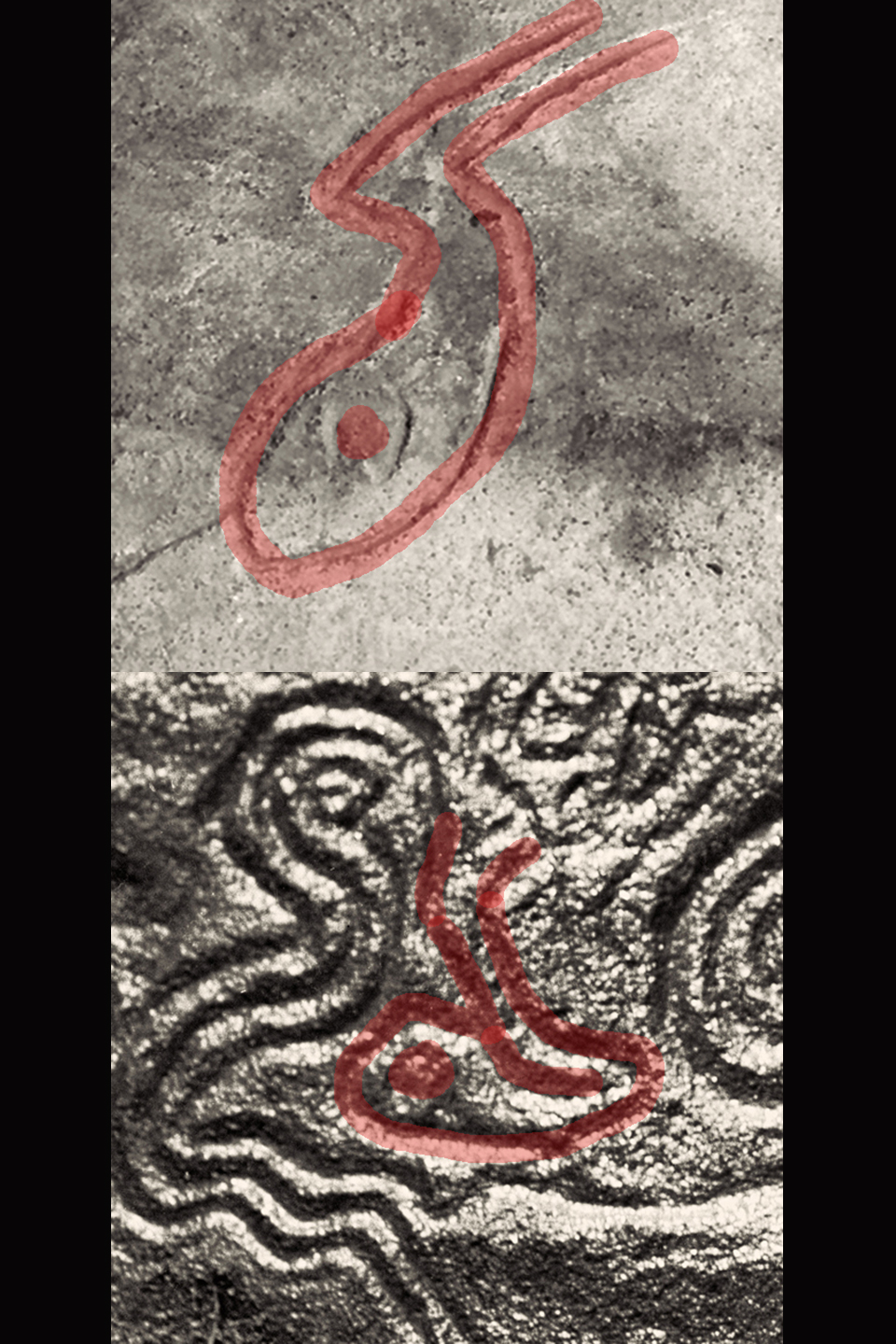

Below, a photo of the back side of the ‘human jaguar’ mold, which is marked with a glyph of some sort. The Tumacos are not known to have had a system of writing, so the glyph is most unusual. The dealer who offered the mold for sale believed it to be a signature, a “mark of the artist.” That’s an intriguing theory, but of course there’s no way to prove it–or to disprove it!

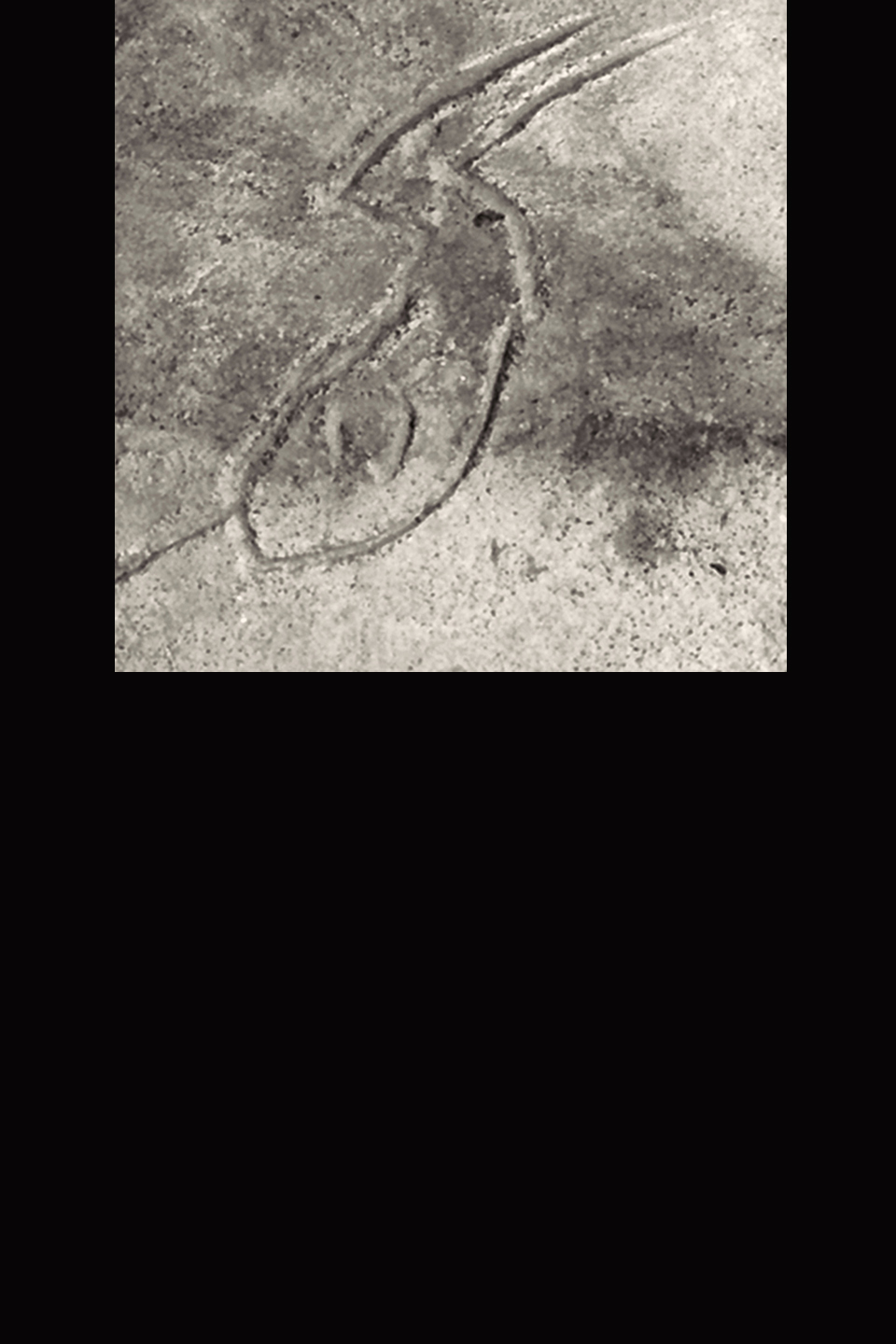

The slide show includes a comparison of this glyph with a petroglyph located deep in the Cauca jungle, some 200 miles north of Tumaco. The photo shows a portion of what is believed to be a snake, carved into a large boulder rising from a jungle stream. The petroglyph is of unknown origin, and any connection with the Tumaco culture is purely speculative. Still–it’s a tantalizing possibility!

A few more Tumaco figurines. Click any photo to expand the images to full screen.

Unless otherwise noted, all of the images on this site are my original work and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

If you’re interested in the Tumaco Culture, check out the rest of the series. Next up: Tumaco: Part 2: From Out of the Flood.

Disclaimer: I am not an academic. The assumptions made and the conclusions drawn in these posts are those of a reasonably well-informed enthusiast; I haven’t put in the work that might make me an expert. At one time, I was up to my neck in this stuff, but the most that entitles me to is an opinion.

MORE SOUTH AMERICAN ADVENTURES:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

South America Before the Conquistadores

Tumaco: Atrocity Trumps Antiquity on the Coast of Colombia

Within a matter of a few years, every readily accessible site had been looted and stripped of artifacts. There were laws in Ecuador prohibiting trade in antiquities, but during the 1970’s, there was no such law in Colombia, so the Tumaco heritage, extraordinary in its complexity, was scattered to the four winds.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

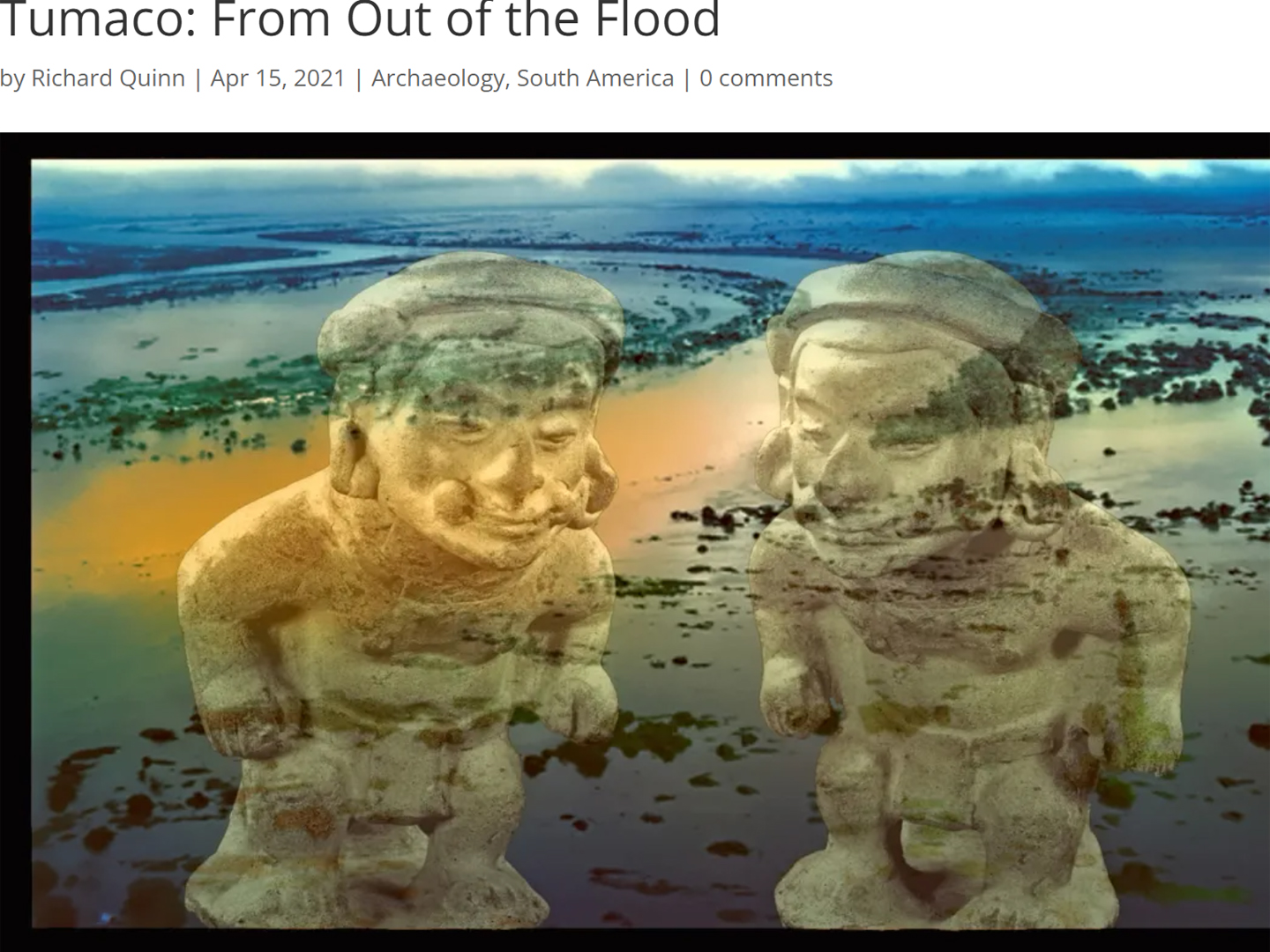

Tumaco: From Out of the Flood

Far more common than the precious metal were the artifacts made of clay, small, often elaborate figurines depicting nearly every aspect of the people’s daily lives, as well as their animistic mythology. It is through those figurines, some intact, but most in fragments, that these all but forgotten people have come to be known.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

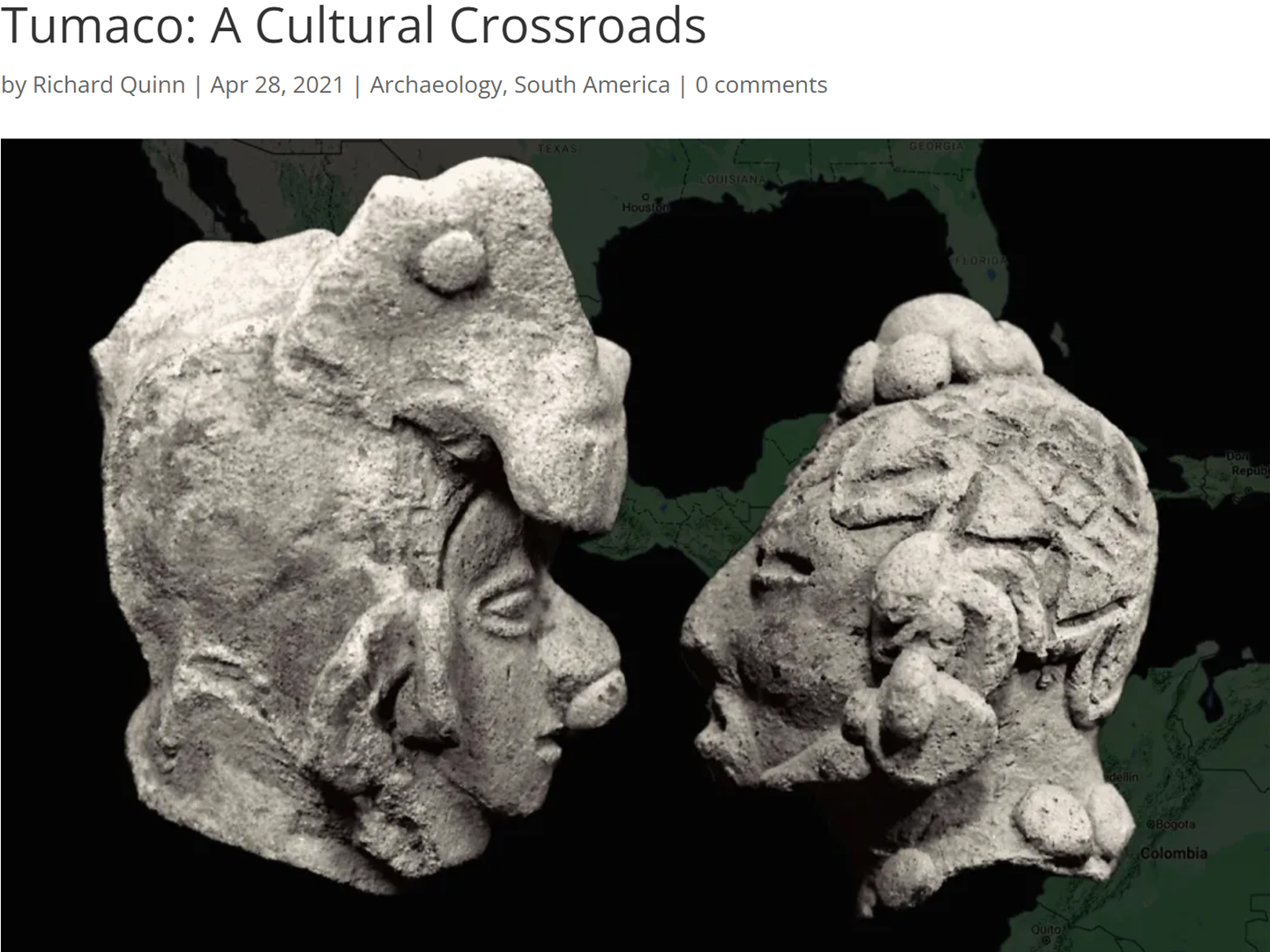

Tumaco: A Cultural Crossroads

Traders coming down from the north had to endure many days of difficult travel along a coast that’s tough to negotiate even today. The reward must have been worth the trouble, because men from the Yucatan did, in fact, make that journey, trading goods, as well as ideas with the men of Tumaco.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

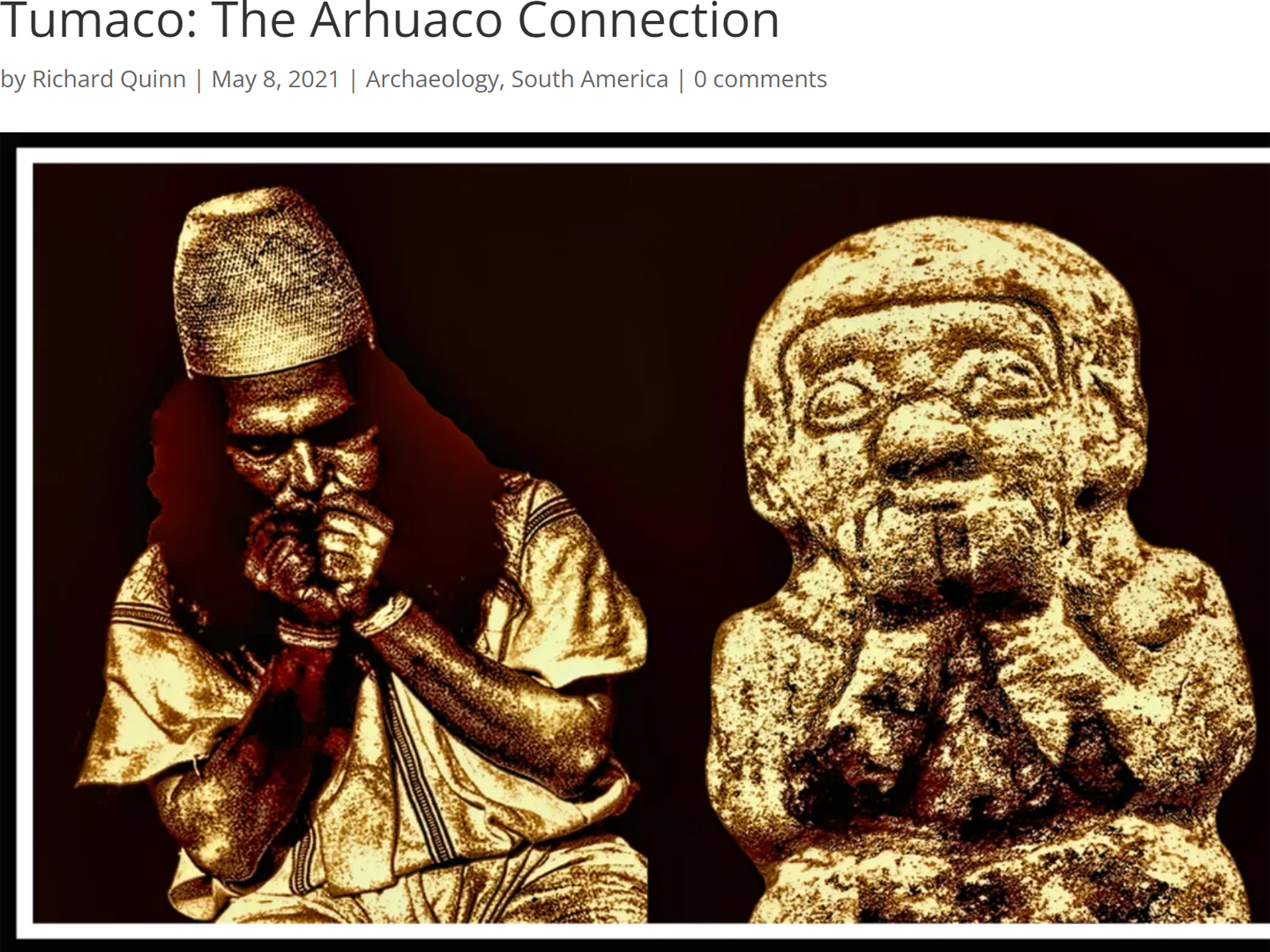

Tumaco: The Arhuaco Connection

What we really know of history is like an ancient tapestry, worn, and threadbare, with missing patches confusing the grand design. When we make a new connection, we restore a missing thread, and little by little, thread by thread, we fill in those troublesome blanks.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

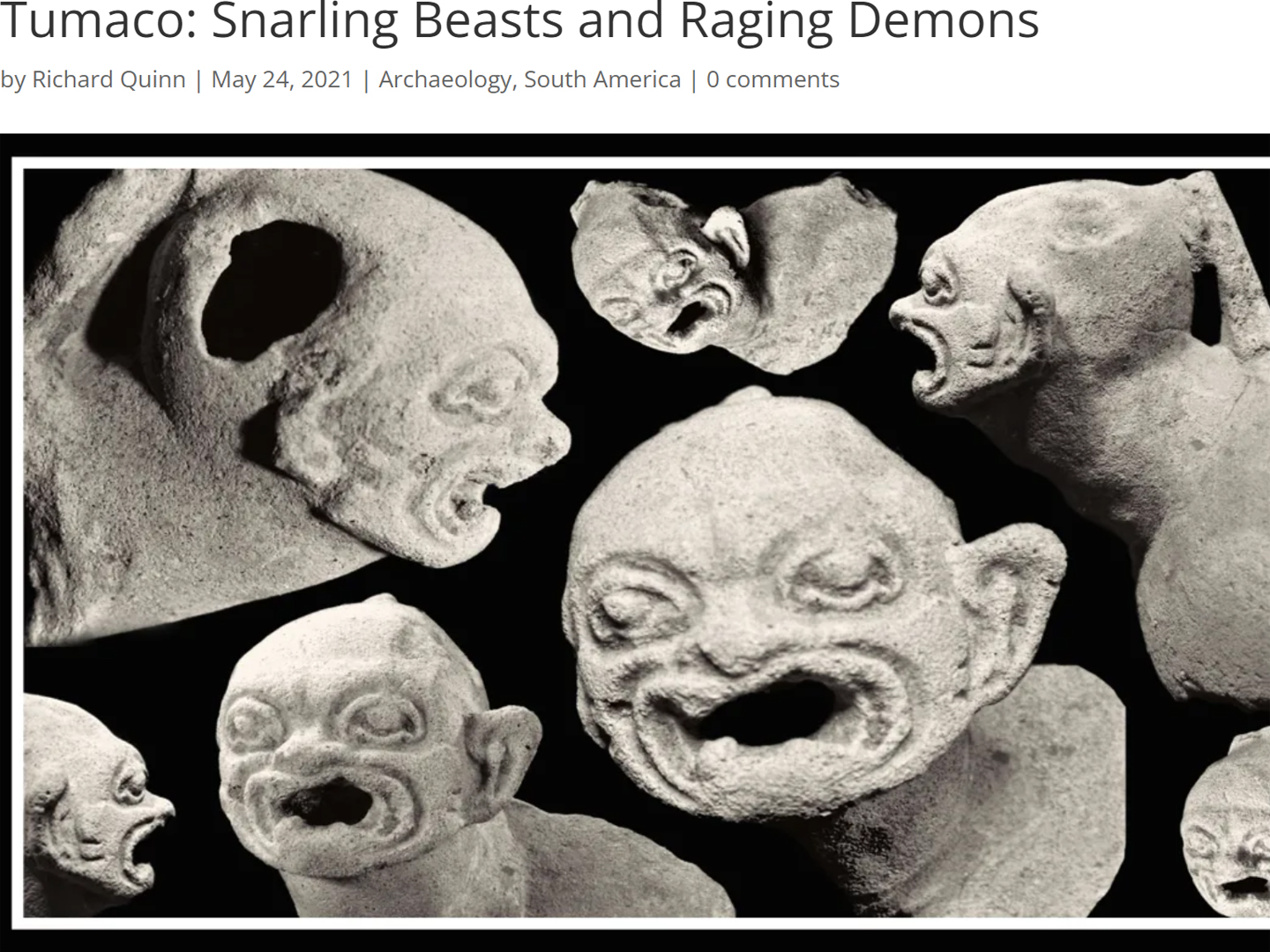

Tumaco: Snarling Beasts and Raging Demons

There was so much ancient pottery in the Tumaco area that it literally washed up out of the ground after every big rain. With so many men out there looking for gold, it was impossible NOT to find Tumacan ceramics. Strange figurines and fragmented sculptures, unlike anything that had been found before, anywhere else in Colombia.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

In the Vale of the Stone Monkeys: Peril and Petroglyphs in the Colombian Jungle

El Manco was easy to spot; he had embraced his defining handicap, a right arm that had been severed above the elbow, and that wasn’t even his only problem. He was also missing his right eye, nothing there but an empty socket and an ugly knot of scar tissue. “Tough old bird” doesn’t begin to describe a hardscrabble character like Manco; he had a face with creases like a roadmap straight to his own personal version of hell.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Rape of Bahia Concha

It was the Tairona gold that triggered a blood lust in the Spanish invaders, ultimately causing the destruction of the entire Tairona civilization. That cycle was repeated in modern times, when the lust for Tairona gold infected the guaqueros, causing the destruction of the last refuge of the Tairona ancestors, in one final humiliation, one last indignity: the RAPE of Bahia Concha!

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent

Paul dug with his hands then, finally sticking his arm into a hollow space, pulling out a dark object. Grinning at me from the bottom of his hole, he handed up what he’d found. A round blackware vessel representing a coiled serpent, open in the middle, with a spout at the top of the head. I’d seen a lot of Tairona artifacts, but I’d never seen anything remotely like that one.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments