October, 1971

The first time I saw Bahia Concha was in October of ’71, when my buddy Paul drove me out there in a borrowed Land Cruiser. He’d been talking about the place for as long as I’d known him; it was like his personal holy grail. A dig that was so accessible you could drive right up to it, with sandy ground so soft you could almost use your hands. He claimed to have witnessed the excavation of an important chief who had been buried with a gold nose ring, lip plug, ear rings, necklace with a cacique figurine, and even a gold breast plate. There were dozens of ceramic vessels, hundreds of carved stone beads, shell ornaments, whistles, axe blades, you name it. The total take was worth fifty grand, easy, and that was just one burial! The overall site was huge, or so he claimed, so there was no way they could have dug it all out yet.

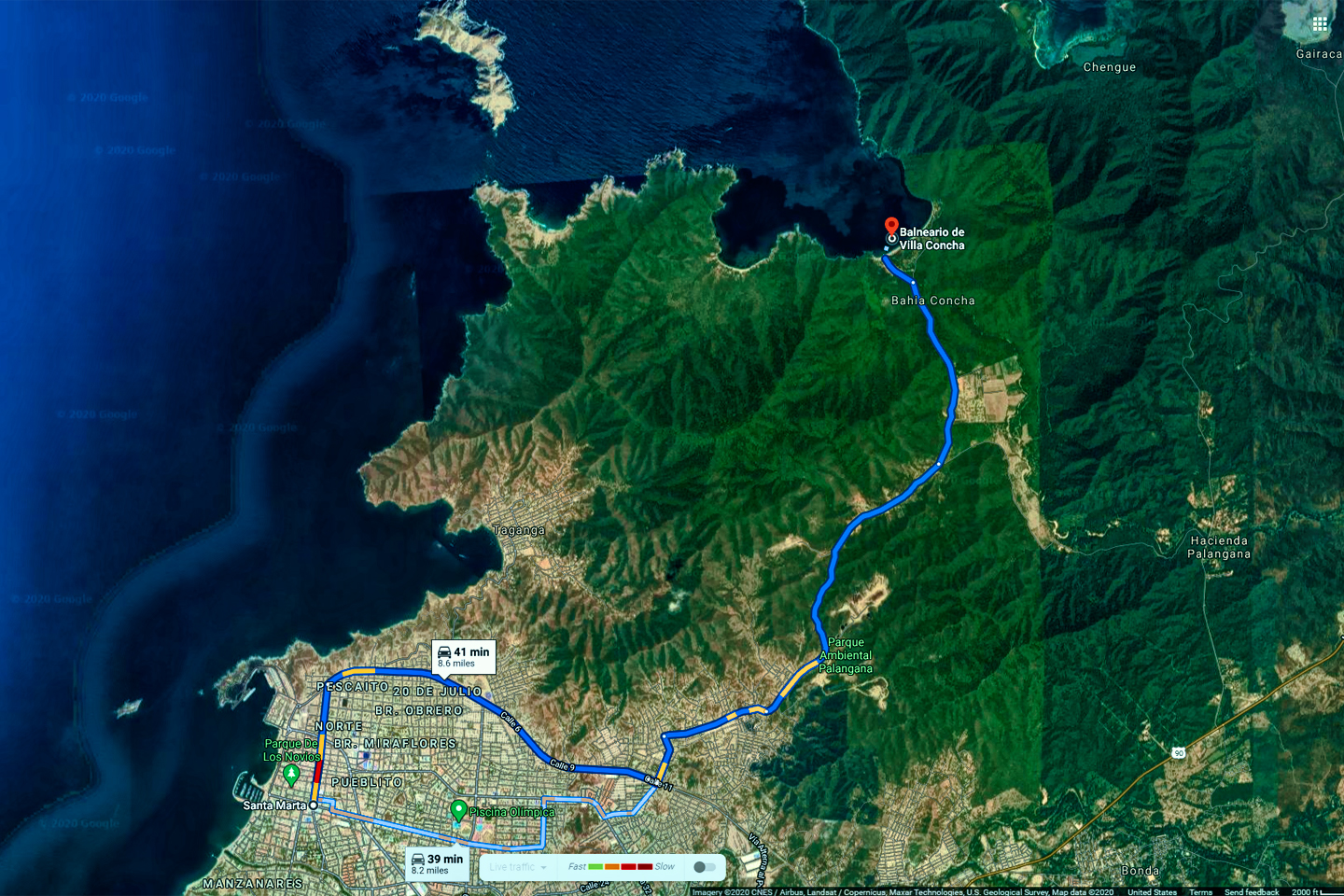

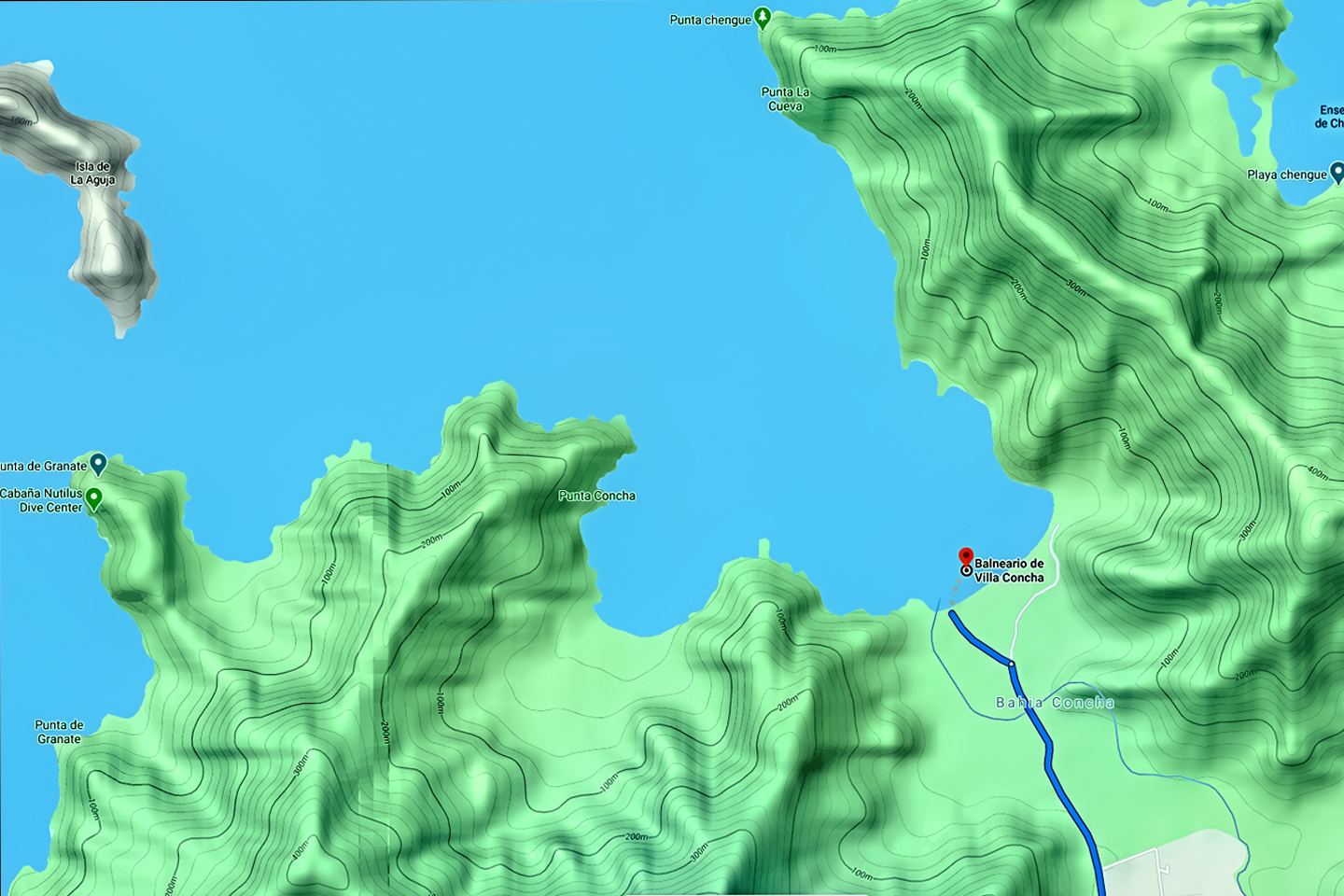

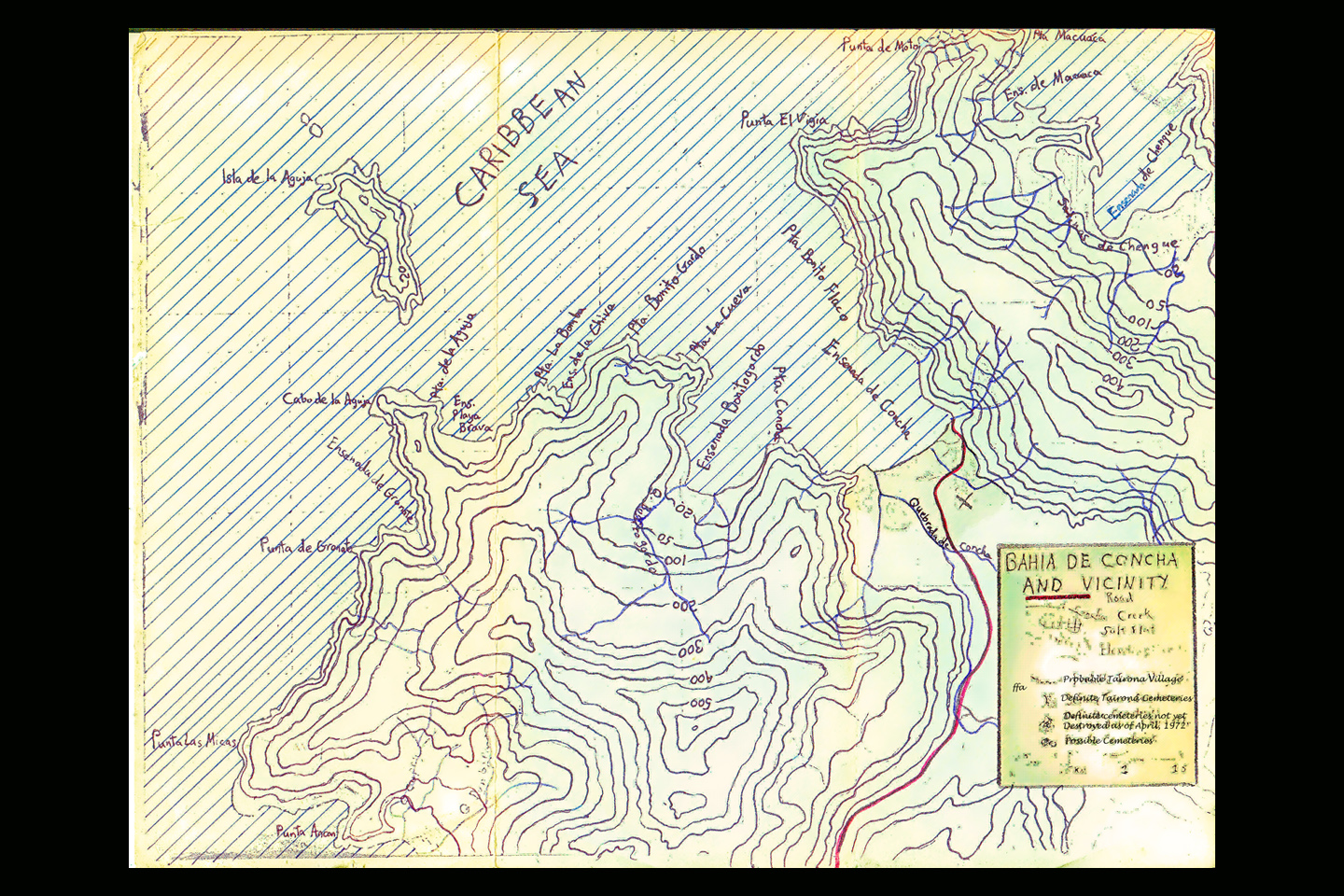

The two of us had just spent six weeks on a dig in southern Colombia, putting in an enormous amount of effort that hadn’t yielded a single scrap of broken pottery. The whole time we were there, working on a mountaintop that was literally above the clouds, Paul simply wouldn’t shut up about Bahia Concha. He was perfectly capable of exaggerating when he was trying to talk me into something, but this time, I’d given him the benefit of the doubt, and the moment we finished our mountaintop project, we hopped a plane up to Santa Marta. When we got there, we didn’t waste any time: Paul looked up his friend Jose, who loaned us the Land Cruiser, and off we went. I was surprised by how close Concha Bay was to the city, less than 30 minutes by road. I’d already heard all about the Tairona cemetery that had been plowed open by the bulldozer, but on the drive out there, Paul quite naturally told me the whole story again. “Me and Jose and his cousin Raul were right in the middle of it, the very first week,” he said. “You wouldn’t have believed it, all the stuff guys were finding.”

“Way back in January,” I said. “That’s a long time ago.”

“True,” Paul replied. “Almost a year, but like I said, this place is huge.” He stopped the Land Cruiser well short of the beach, in an area where there was thick tropical growth on both sides of the road.

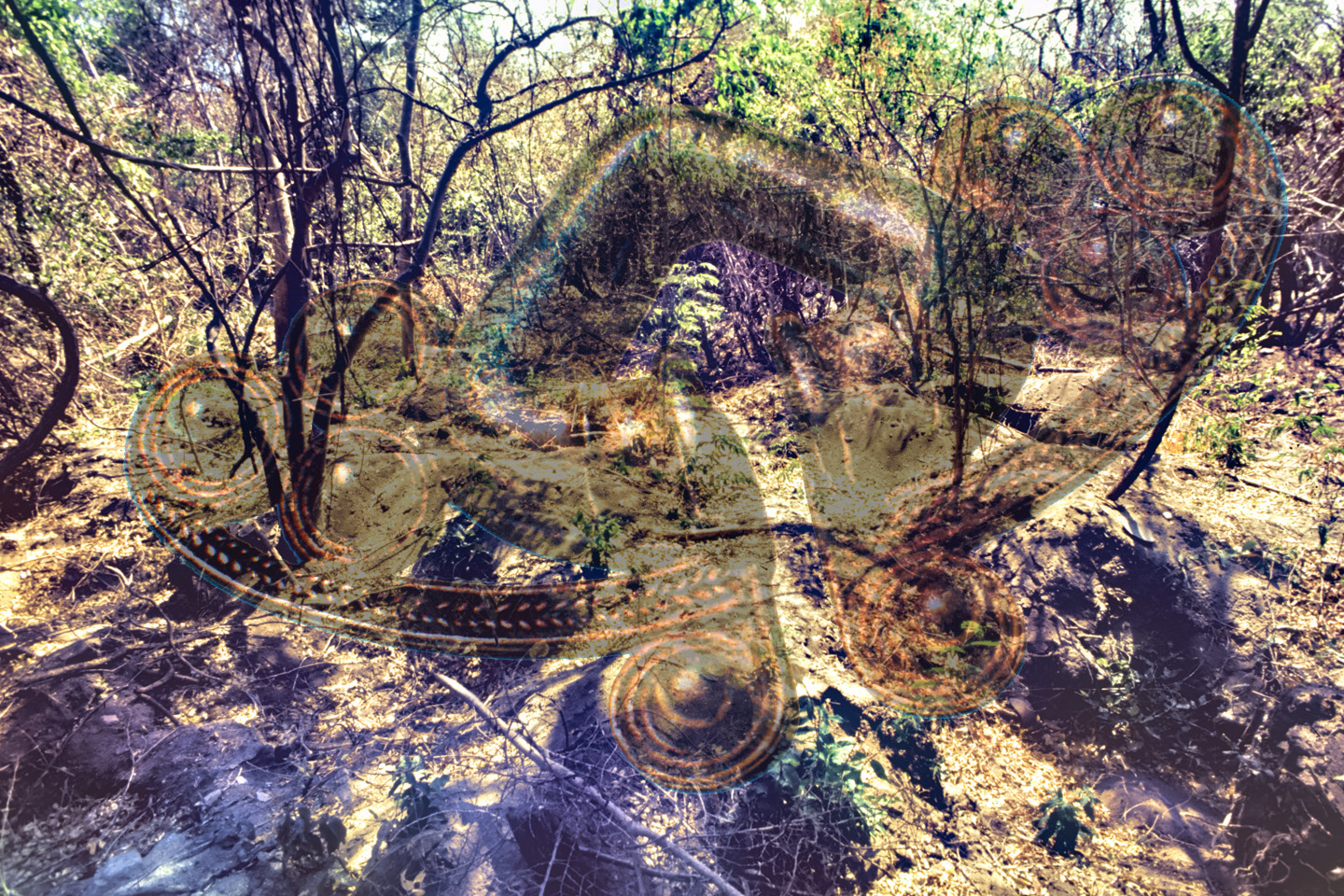

He’d brought along a short-handled trenching shovel and a pair of machetes; we gathered the tools, then hopped the fence on the left hand side. Something was obviously going on there, because the field was chewed to hell, with crater-like holes and mounds of earth in every direction. If this was the Tairona cemetery, it looked to me like it had already been tapped out, and I said so. Paul gave me one of his stupid grins and went on looking, searching for a flat spot of ground that hadn’t been dug up yet. He finally found one, about ten meters back from the road, behind a thick screen of thorny brush. He probed with his shovel, and hit nothing but rocks, so he dug down a couple of feet, and probed again. That time, we heard the distinctive <<TOONK>> of steel striking hollow clay. Paul dug quickly then, uncovering a red clay urn at least two feet in diameter, with a face molded into the side of it. Before we had a chance to so much as clean off the dirt, we heard the sound of a vehicle stopping over on the road, and voices. Paul put a finger to his lips, cautioning me to be quiet; he didn’t need to remind me that we did NOT have permission to be there. We couldn’t very well hide, not with that Land Cruiser parked where it was, so I left Paul crouching in the hole that he’d dug, and I circled back to the road, far enough to the rear that I couldn’t be seen. I crawled back under the fence, dusted myself off, then walked nonchalantly up the road , carrying my camera. A beat-up Land Rover was parked behind the Land Cruiser, and three men were standing by the fence, two workers, and an older gentleman, better dressed, obviously the man in charge.

“Is this your vehicle?” he asked as I approached.

“It belongs to a friend,” I replied. “Is there a problem?”

“This is my property,” he informed me. “All of this, everything you see. And I have a big problem with trespassers, sneaking onto my land and stealing from me.”

I assured him that I was only a tourist, on my way to check out Villa Concha, and that I hadn’t taken anything but photographs. I played dumb, and asked him what was going on in his field, all the holes and piles of dirt. He softened his gruff manner, just a little, and explained, in basic terms, about the Tairona cemetery. He said that he had men working for him out there, digging up artifacts, but they were all on the other side of the field, closer to the river. There was a fair-sized piece of a broken pot lying in the dirt near the fence. He picked it up, dusted it off, and handed it to me, told me I could keep it as a souvenir. I felt like a complete shit, but I accepted the gift, and thanked him for it. Right about then we heard a shout. The two workmen had just done a quick search of the area while I was talking to their boss, and of course they found Paul, hiding in his hole with that Tairona urn. Don Julio went ballistic, not just because we were stealing from him, but because I had so glibly lied to him, something he found completely unforgivable. That’s when I went off on a tirade of my own, chastising him for allowing the wholesale destruction of an important archaeological site. Nobody with any scientific expertise had so much as looked at that Tairona cemetery; thousands of burials, hundreds of years of history, and all the knowledge that might have been gained was as good as lost. I was only a student at that time, but I begged him to allow me to record some of what was going on with my camera and my notebook, before it was too late. It was clear that I’d struck a nerve with that argument. He asked me a series of pointed questions about my background, and my intentions, and finally seemed satisfied.

“I’ll allow the two of you to work in there,” he said, gesturing toward the dug-up cemetery. “Come back tomorrow, and look for my man Gomez. He can show you around, and get you situated. I’ll let him know you’ll be coming.”

“What about this?” asked Paul, still holding the urn.

“Keep it,” Don Julio said with a shrug. “If you do any more digging, half of anything valuable goes to me. And stay out of the field on the other side of the road. I have cattle over there, so digging is NOT allowed. Agreed?”

We shook his hand, feeling like we’d just dodged a bullet, and watched him drive away. Back at our hotel, we cleaned up the urn, which was still full of dirt, and much to our surprise we found a second, smaller urn nested inside, I’ve never been quite sure of the significance, but I’ve always thought that was pretty cool.

The next day, we drove back to Bahia Concha, and parked in more or less the same place. I started for the fence on the left hand side of the road, planning to head off in search of Alvaro Gomez and his crew of guaqueros, but Paul made no move to follow me. “What?” I said, turning back to see what he was up to. “You’re not coming?”

“We’ll never find anything if we work alongside everybody else,” he said. “We need to break some new ground.”

“What did you have in mind?”

Paul shot me a wink, grabbed his shovel, and hopped over the right hand fence, into the explicitly forbidden pasture. “We can go back that way 100 yards or so.” he said, gesturing toward a thick wall of thorny brush. “You’ve seen how easy the digging is. We can be in and out before anybody knows we’re there. This is virgin territory! We could strike it rich on the first try!”

Paul was notorious for his bad ideas, and this one looked to be a classic. Still, since I was the one who’d made those promises to the old man, I was on the hook whether I went along with it or not. I reluctantly hopped the fence, and followed Paul into the bosque espinoso, both of us swinging machetes, chopping back vines with razor sharp spines, just to clear a barely adequate path. We reached an area that Paul judged to be far enough back from the road, and he stuck in his shovel. We were closer to the mountain at the valley’s edge, so the soil here was hard and rocky, not soft sand. Paul dug a bit more, probing with his shovel, which clanged sharply, repeatedly striking rocks the size of footballs, .

“This is no good,” I said, peering into his hole. “We’re past the boundaries of the graveyard. They wouldn’t have put any burials here; this dirt is like cement.”

“I’ve got one of my intuitions,” Paul retorted. “Not like down in Cali. I really think there’s something here. Right here.”

He didn’t need to remind me about Cali, or the “coal mine” that he’d dug in the top of that mountain down there. I just didn’t want to get caught on the wrong side of the fence again, not twice in two days. I took another look at his hole. “How rocky is it?” I asked, already knowing the answer, kicking at his pile of dirt with the toe of my boot.

“Not that bad. And there’s softer dirt over here on the side, looser, like maybe it’s been dug before. Isn’t that what you taught me?”

“Of course,” I said, since I couldn’t very well deny it. “If the dirt has that loose feel to it, follow where it leads. But if you don’t find anything worthwhile in the next hour, we move back across the road. Agreed?”

Paul agreed, and turned back to his digging, wielding that little shovel with a vengeance. I didn’t really have any control over Paul. He was 10 years older than me, an ex-Marine, and tough as they come. He most definitely wasn’t the smartest friend I’ve ever had, but he was fearless, strong as an ox, and every bit as tenacious; qualities that were quite useful in some situations, a serious problem in others. Right at that moment, on the wrong side of the wrong fence at Bahia Concha, he was like a dog with a bone, and I knew better than to get between him and his quarry.

The soil was alternately hard and soft, rocky and sandy. Paul kept digging for most of that hour, and he created a hole at least four feet deep, with a side chamber. He paused for a moment, and handed up a large rock, flat on both sides. “You see this?” he said excitedly. “It’s a plancha. That’s like a Tairona headstone!”

“Seriously?” I turned the thing over in my hands. There was no carving on it, no tool marks to indicate anything other than a natural, flat stone. “If it’s a grave marker, why would they bury it so deep, totally out of sight?”

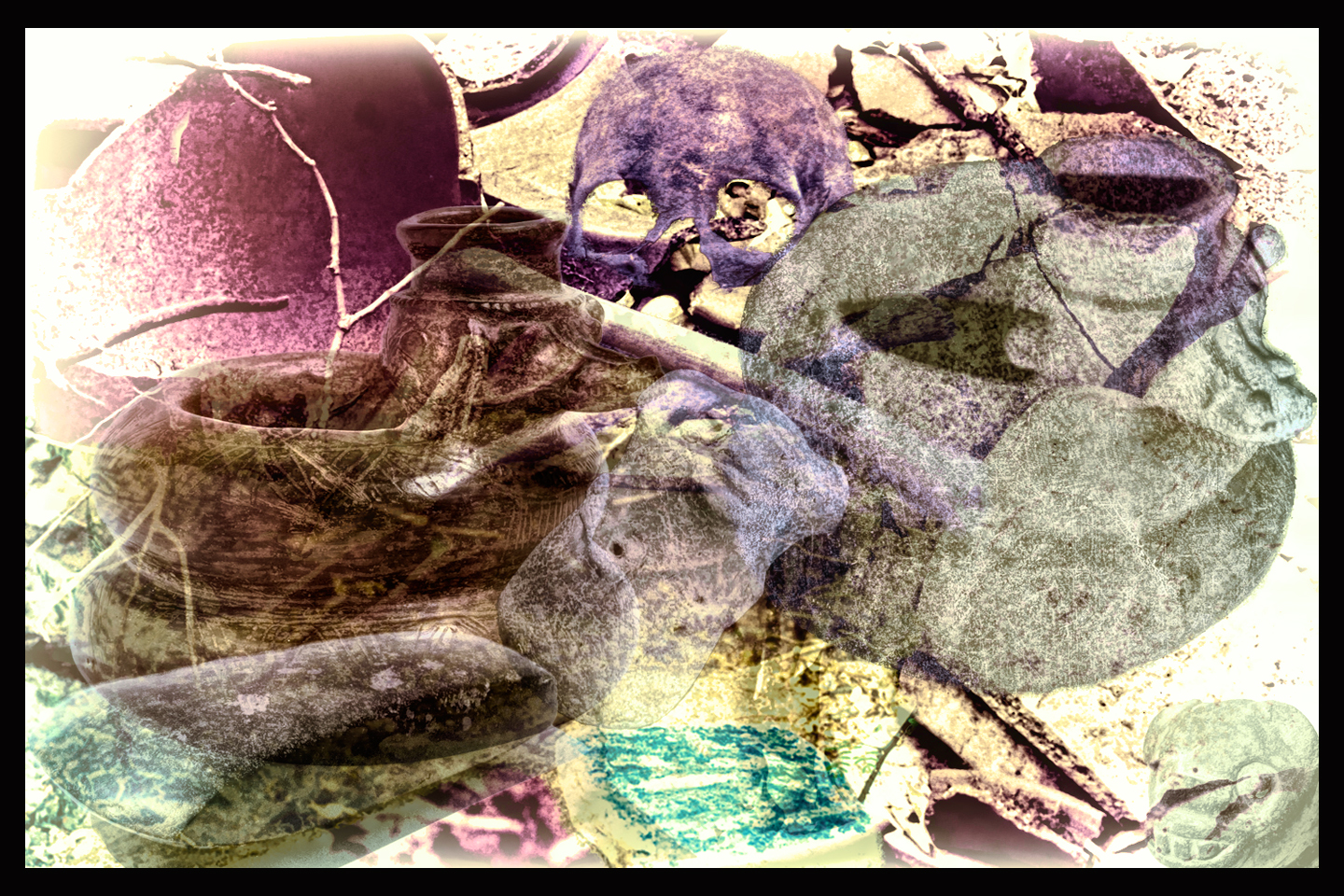

“Good question,” said Paul, “Maybe they didn’t want anybody to find it!” He turned back to his digging, enlarging the hole where the dirt was softer. He probed sideways with his machete, and stopped. <<TOONK>> There was that sound again, but softer. Paul dug with his hands then, finally sticking his arm into a hollow space, pulling out a dark object. Grinning at me from the bottom of his hole, he handed up what he’d found. A round blackware vessel representing a coiled serpent, open in the middle, with a spout at the top of the head. I’d seen a lot of Tairona artifacts, but I’d never seen anything remotely like that one. It was truly one of a kind, and there was certainly no question of its authenticity.

There was nothing else of value in that particular grave, and indeed, there was no getting around the fact that this was, in fact, a grave. Paul found the skull, with the jaw detached, and set it to one side. Most of the other bones had long since decayed into dust, so we scraped them aside, as respectfully as possible, and we kept digging. We found fragments from two other ceramic offering vessels that had been completely destroyed by roots, along with one battered, well-used stone axe blade, and a pestle, of the sort used to crush herbs and seeds. There was no carved stone jewelry, and most definitely no gold. I often wished, in later years, that I’d had the time and resources to properly excavate that “forbidden” section of the cemetery. Up to that point, it was still completely undisturbed. There were untold mysteries in that field that would never be examined, much less resolved, but if I wanted to stay on the good side of Julio Sanchez, we had to stay on the proper side of his fence, and that meant no more digging where we’d been told not to go.

The above is a terrible picture, but it’s the only photo I’ve got of the “snake pot” that Paul and I dug out of the ground at Bahia Concha. Tragically, all of the existing prints of the photos I took that day were destroyed, along with the original negatives, when the house where I’d been living, on a coffee farm near Pasto, was nearly washed away in a flood. This single image was the best I could salvage when I scanned a strip of 35mm film that had been buried for two weeks under three feet of mud. What doesn’t show in this heavily edited photo is the gray, almost cement-like clay that was stuck to the piece, particularly in the center; the incised markings, simulating a serpent’s scales, on the coils of the pot; and the single deep scratch on the top coil from Paul’s probing machete (<<TOONK>>), just out of view of the lens.

I originally wanted to keep the snake pot, as my share of our mutual enterprise, and Paul agreed, because he owed me money. Sadly, when he and I parted company, about six months later, the rascal took it, and he sold it, and then he disappeared. I never saw the snake pot–or the money I was owed–ever again.

In hindsight, it’s entirely possible that I got off easy…

CURSE OF THE COILED SERPENT

There was a time when I came to believe that the snake pot, the coiled black serpent, was cursed. The more I thought about that burial, off by itself at the far edge of that Tairona cemetery, the more convinced I became that it was the final resting place of a shaman, or a witch, an individual possessed of dark powers. Snakes, especially snakes that are coiled and ready to strike are directly associated with shamans in many Native American cultures, and the cross hatched pattern on the coils identified the serpent as venomous, reinforcing my theory about malevolent magic. Either way I was convinced, in a very visceral way, that we should not have disturbed that artifact.

I had a string of seriously bad luck after finding that thing. For the next several years, every April, almost like clockwork, something horrible would happen to me. Year one, just a few months after we found it, the police raided my rented house in Bahia Concha, looking for Paul, who was always in some sort of trouble. He ran out the back, so they arrested me instead, and I spent three weeks in the worst prison in the world while they sorted out their mistake. Exactly one year later, my best friend, my dog Lobo, contracted a strange disease and died, quite abruptly, with his head in my lap in a Bogota hotel room. The year after that, my home on the coffee farm near Pasto was washed away, along with most of my possessions (including all of my photos of that dig, and the ‘evil artifact’). Finally, in the spring of year four, my export business imploded, costing me every penny I had, and several close friendships. Those disasters kept happening, year after year, until I left Colombia for good, flat broke, in May of 1975.

Looking back on that period of my life, decades later, it occurred to me that each of those tragedies mirrored, in a strange, and of course much smaller way, the terrible things that happened to the Tairona, the losses that they suffered as a people. Each painful incident taught me an important lesson, and each bout of deeply personal suffering left me stronger, smarter, and better equipped to handle the exigencies that shaped my life as it unfolded in later years. I can see now that if there really was some nefarious energy released when we dug up the shaman’s grave, it was balanced, or tempered, like yin and yang, by an ancient, benevolent wisdom. (If that makes any sense at all!)

My old friend Paul, the person most responsible for disturbing that burial, fared much worse than I did. Colombia has always been a dangerous place, and there are some lines in the sand that you just don’t cross. Paul’s penchant for “digging where he’d been told not to go” ultimately got him killed, and according to whispered rumors, he ended up buried in an unmarked grave of his own…

~~~~~~~

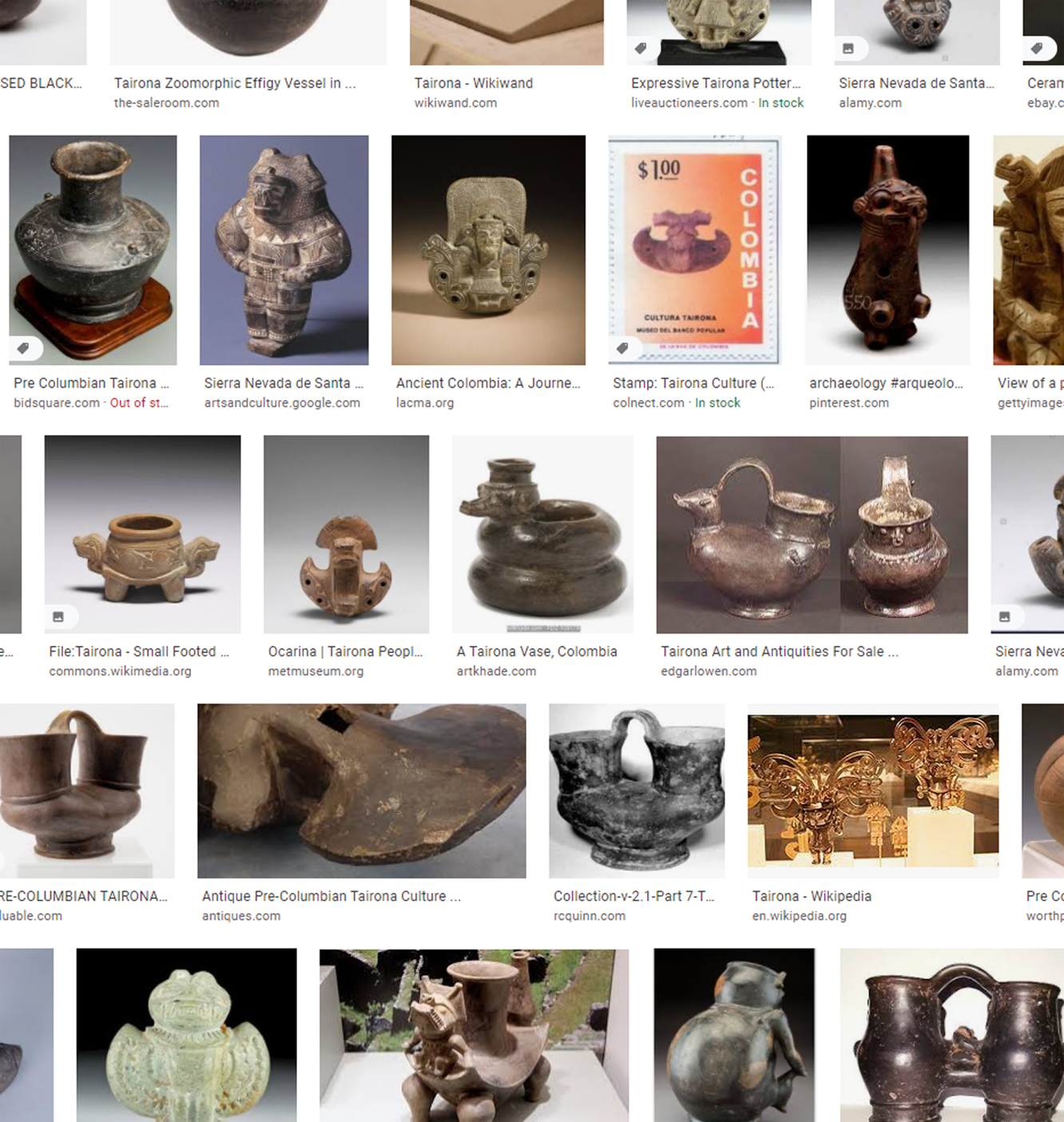

Fast forward 48(!) years: A few months ago, I was doing some unrelated noodling around on the internet, and out of the blue, I had an odd compulsion to run a Google Image search on “Tairona Ceramics.” My search retrieved a diverse grid of thumbnails, each one linking to a web page or a stock photo, and nestled in there among them was a surprise that actually stopped my breath for half a beat:

The photo is from the Artkhade Database, and shows a “Tairona Vase” that was sold at an auction in Paris in 2017.

Is it the same piece? It matches my original down to the smallest detail, including the single deep scratch on the top coil. Could that be the very same gouge left by Paul’s machete? <<Toonk!>> That would make this a very small world–but when it comes to Tairona blackware vessels that are shaped like coiled serpents? I should imagine that ours is a very small world, indeed.

For whatever it’s worth (and in hope that the winner of that Paris auction kept their purchase in Europe): I derive considerable comfort from the knowledge that an ocean and most of a continent lies between me and that coiled serpent!

Many of the photographs in these two slideshows (below) were shot on 35mm film, which was scanned and edited to clean up scratches and flaws in the emulsion, the result of half a century of incautious handling and less than ideal storage conditions. They’re not perfect. Consider them as you would those historical photos, in a really old National Geographic!

Click any of the images to blow them up to full screen, with captions:

(Unless otherwise noted, all of the images in these posts are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.)

This is a true story, though some of the names have been changed, and certain exchanges had to be modestly fictionalized (since my memory of the events appears to be missing the sound track). The rest of it, including the very personal consequences of the curse, I’ve written just as it all went down, all those years ago…

For the record: I am not an academic. The assumptions made and the conclusions drawn in these posts are those of a reasonably well-informed enthusiast; I haven’t put in the work that might make me an expert. At one time, I was up to my neck in this stuff, but the most that entitles me to is an opinion.

Questions, comments, and criticism: always welcome!

Be sure to check out the first post in this series: Tairona Gold: The Rape of Bahia Concha

MORE SOUTH AMERICAN ADVENTURES:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

South America Before the Conquistadores

Tumaco: Atrocity Trumps Antiquity on the Coast of Colombia

Within a matter of a few years, every readily accessible site had been looted and stripped of artifacts. There were laws in Ecuador prohibiting trade in antiquities, but during the 1970’s, there was no such law in Colombia, so the Tumaco heritage, extraordinary in its complexity, was scattered to the four winds.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

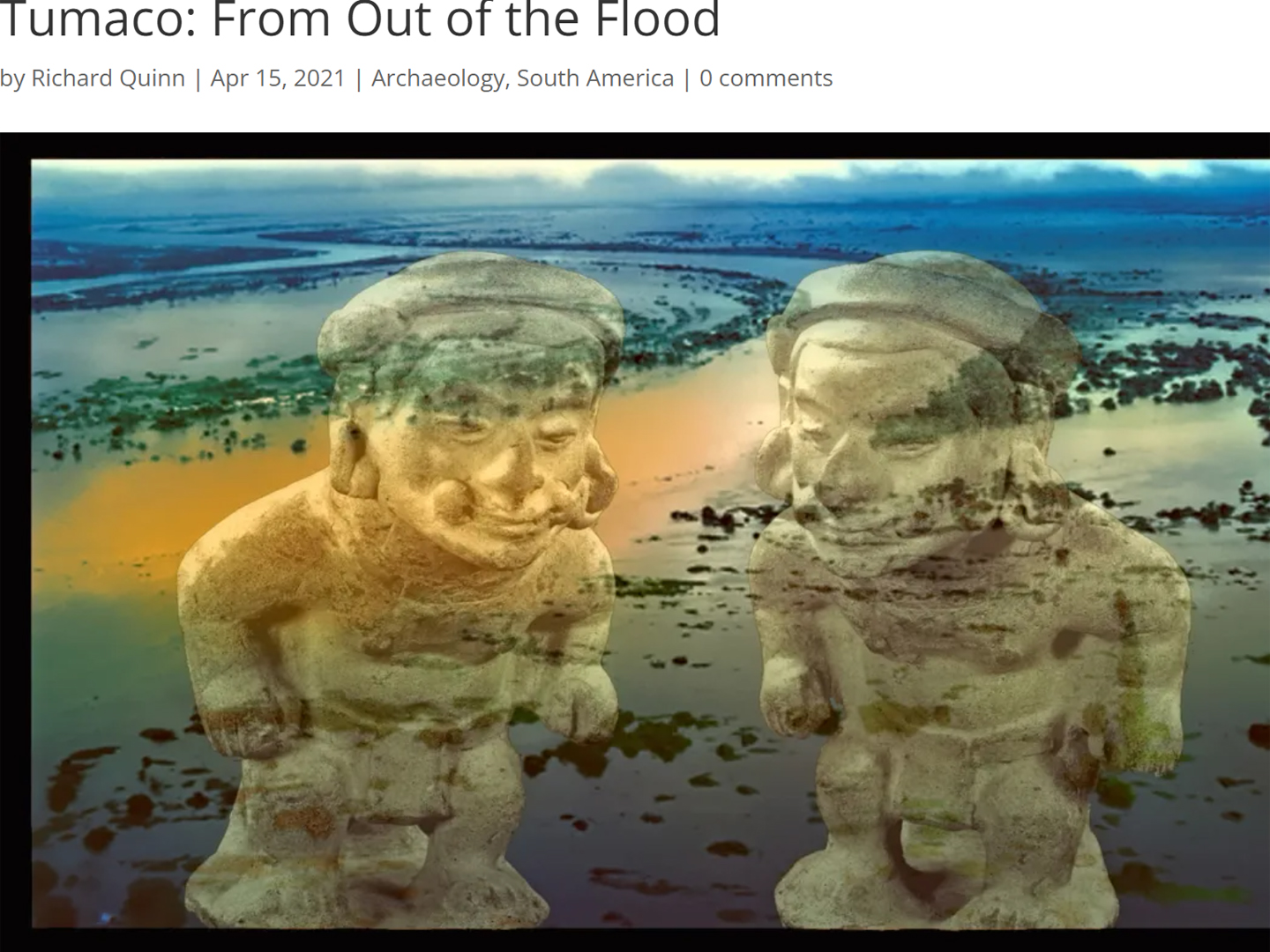

Tumaco: From Out of the Flood

Far more common than the precious metal were the artifacts made of clay, small, often elaborate figurines depicting nearly every aspect of the people’s daily lives, as well as their animistic mythology. It is through those figurines, some intact, but most in fragments, that these all but forgotten people have come to be known.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

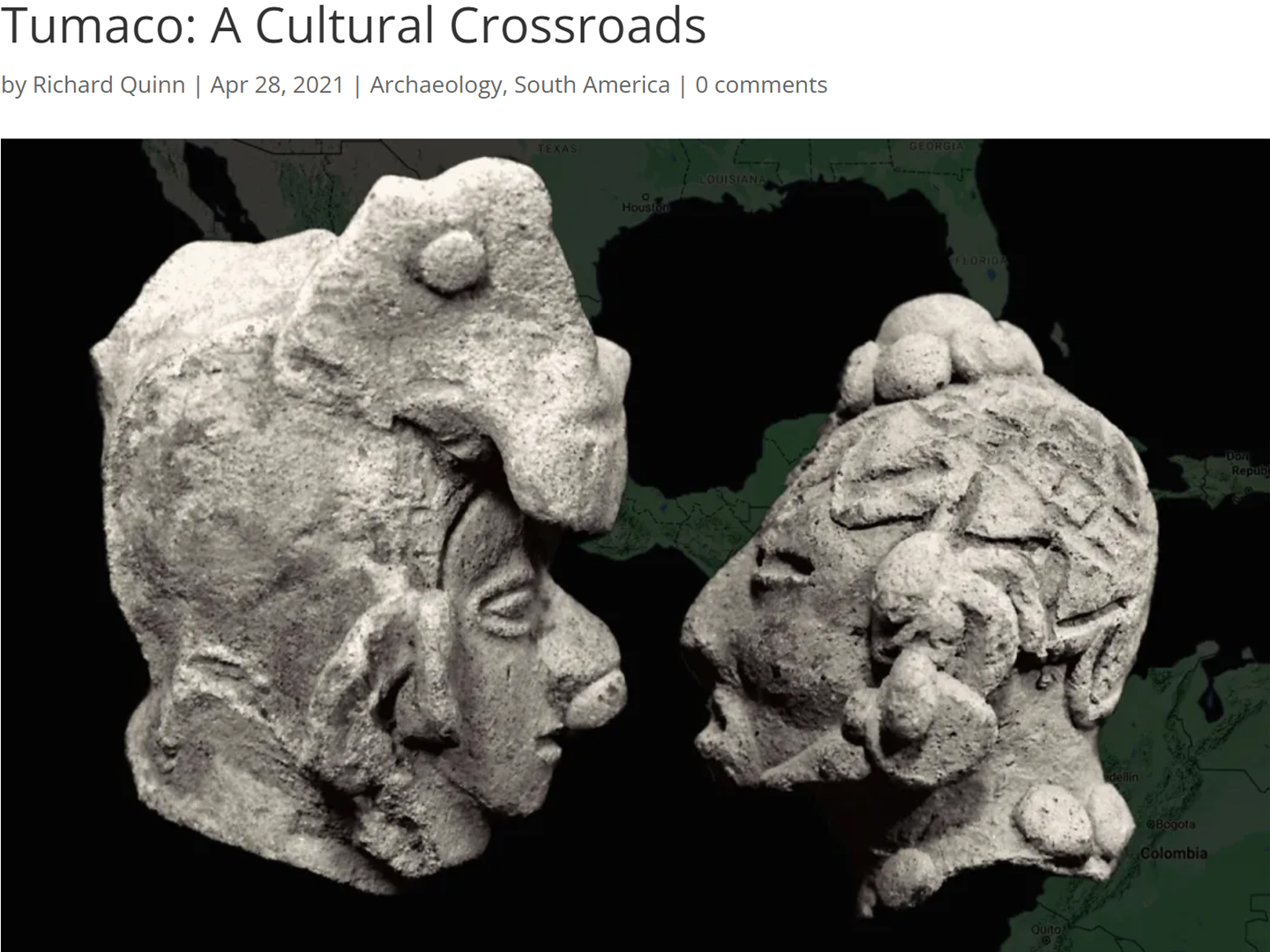

Tumaco: A Cultural Crossroads

Traders coming down from the north had to endure many days of difficult travel along a coast that’s tough to negotiate even today. The reward must have been worth the trouble, because men from the Yucatan did, in fact, make that journey, trading goods, as well as ideas with the men of Tumaco.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

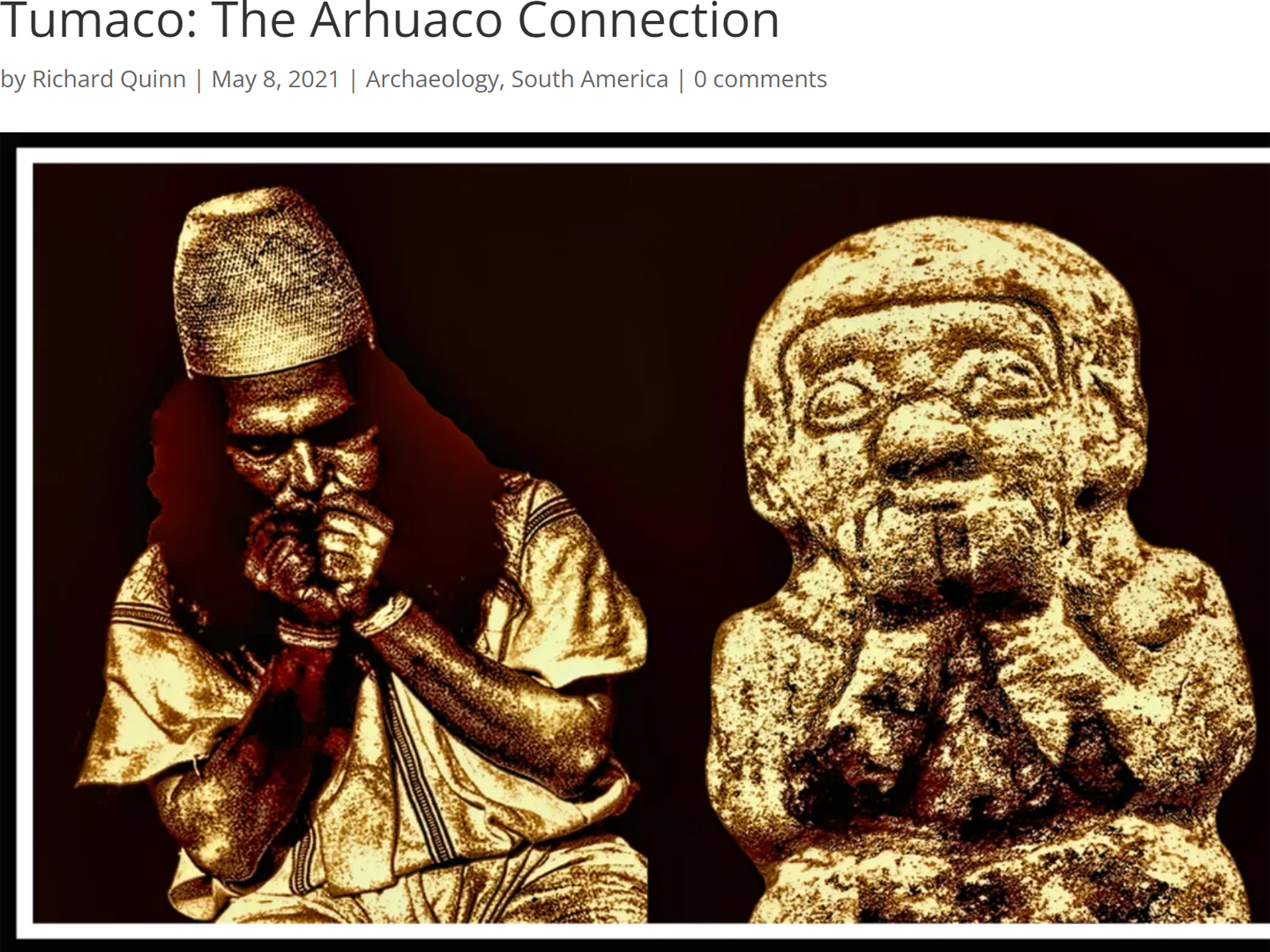

Tumaco: The Arhuaco Connection

What we really know of history is like an ancient tapestry, worn, and threadbare, with missing patches confusing the grand design. When we make a new connection, we restore a missing thread, and little by little, thread by thread, we fill in those troublesome blanks.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

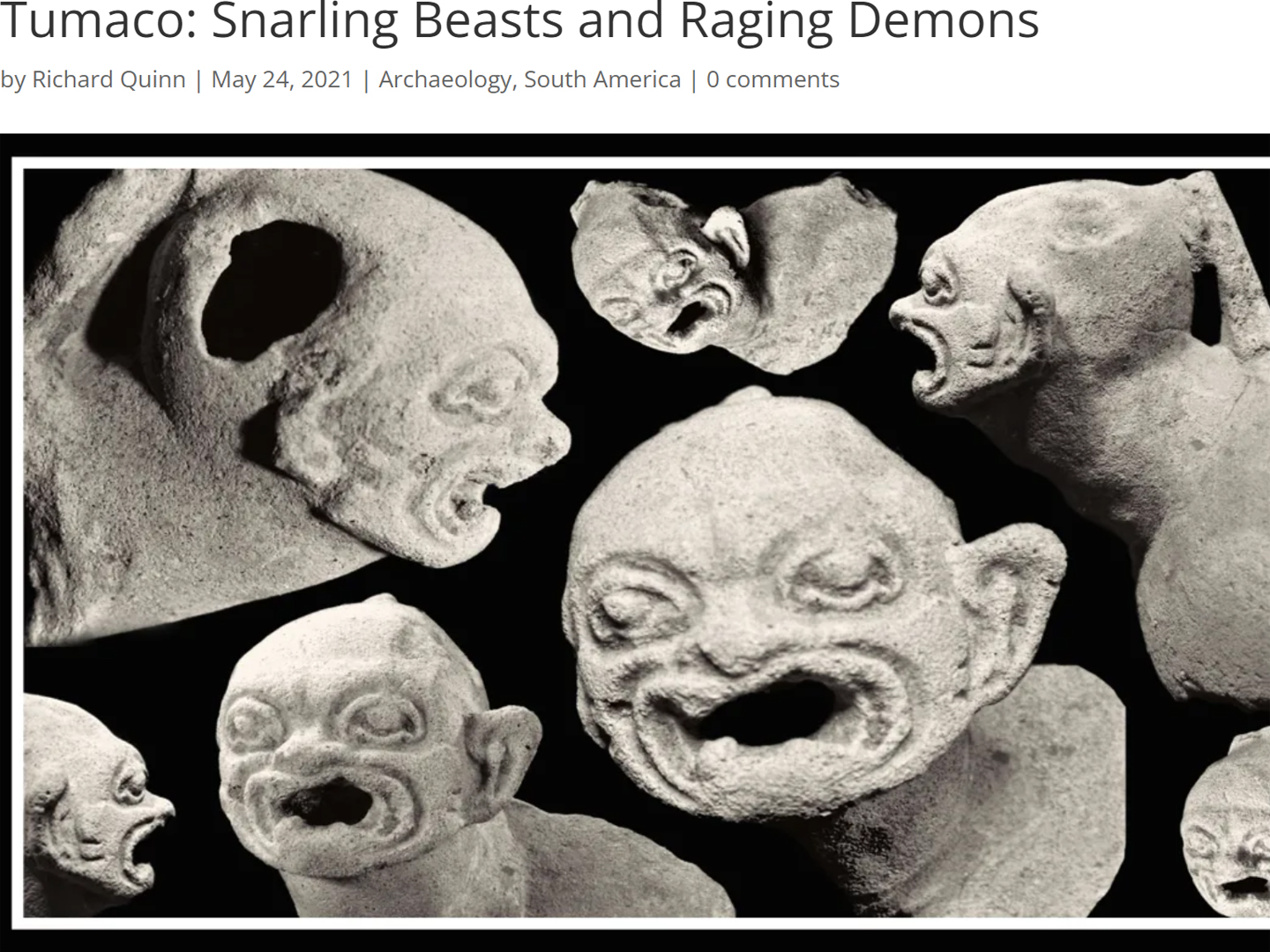

Tumaco: Snarling Beasts and Raging Demons

There was so much ancient pottery in the Tumaco area that it literally washed up out of the ground after every big rain. With so many men out there looking for gold, it was impossible NOT to find Tumacan ceramics. Strange figurines and fragmented sculptures, unlike anything that had been found before, anywhere else in Colombia.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

In the Vale of the Stone Monkeys: Peril and Petroglyphs in the Colombian Jungle

El Manco was easy to spot; he had embraced his defining handicap, a right arm that had been severed above the elbow, and that wasn’t even his only problem. He was also missing his right eye, nothing there but an empty socket and an ugly knot of scar tissue. “Tough old bird” doesn’t begin to describe a hardscrabble character like Manco; he had a face with creases like a roadmap straight to his own personal version of hell.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Rape of Bahia Concha

It was the Tairona gold that triggered a blood lust in the Spanish invaders, ultimately causing the destruction of the entire Tairona civilization. That cycle was repeated in modern times, when the lust for Tairona gold infected the guaqueros, causing the destruction of the last refuge of the Tairona ancestors, in one final humiliation, one last indignity: the RAPE of Bahia Concha!

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent

Paul dug with his hands then, finally sticking his arm into a hollow space, pulling out a dark object. Grinning at me from the bottom of his hole, he handed up what he’d found. A round blackware vessel representing a coiled serpent, open in the middle, with a spout at the top of the head. I’d seen a lot of Tairona artifacts, but I’d never seen anything remotely like that one.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Wonderful stories and those found photos from your friend are really well done. Thanks for sharing.