Bahia Concha, “Shell Bay,” is a sheltered cove on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, located in the Tayrona National Park, just ten miles as the condor flies from the city of Santa Marta. It’s part of a protected ecological preserve where development of any kind is prohibited, so there’s nothing there but a beautiful beach, and some very basic facilities. Public transportation doesn’t go out that far; if you don’t have a car, your best option is a relatively expensive ride in a taxi. That adds to the appeal for those in the know, because it helps keep the crowds to a minimum.

Concha Bay does get its share of tourists, most making a quick stop as part of a package tour of the National Park, but the bulk of the visitors are Samarios, local people from Santa Marta, making a day trip out of a visit to their favorite beach. The quiet bay has coral reefs and schools of colorful fish, perfect for snorkeling and scuba diving, and the relaxed atmosphere is a welcome break from the bustling playas closer to town. In the off season, on an off day, you can walk down that nearly empty shoreline, find a quiet spot, close your eyes, and let your mind travel back in time, to an era when this whole coast was unspoiled, and you could actually have a place like this all to yourself. That’s really not hard to imagine, but it wasn’t always true. If you go back far enough, five hundred years or more, all illusion of solitude will vaporize in a flash, because for most of its history, Concha Bay was a fishing village, not a nature preserve, and there were as many as a thousand people living very busy lives there.

When the Spanish Conquistadors first arrived on the shores of mainland South America, at the beginning of the 16th century, all of the coves along this coast, including Bahia Concha, were already occupied. The site of present day Santa Marta had the best harbor for their ships, so in the year 1525 they established a settlement there, their first permanent settlement on the new continent, and named it for Saint Martha, the patron saint of maturity, strength, and common sense. They had plans to colonize the broader area to the east of their new town, but the natives, known as the Tairona, were fiercely resistant to the idea of sharing their territory. Tairona warriors clashed with Spanish soldiers from the moment of their first encounter, because the Spaniards, quite frankly, were unable to control their greed. The one thing that the Conquistadors valued above all else, even more than land, was gold, and the Tairona, to their everlasting regret, had a LOT of gold, which they liked to display in the form of jewelry worn by the men: nose rings, ear rings, gold plugs through their lower lips. The higher the man’s status, the more elaborate his ornamentation, and once the Spaniards got a good look at the Tairona chiefs and their retainers, decked out in the full array of their finest golden regalia, the Tairona, as a people, were doomed. The Spaniards raided Tairona towns with murderous abandon, stealing all the gold they could get their hands on, and making bitter enemies of the survivors. The Tairona gave as good as they got in those clashes, so there were casualties on both sides, setting the stage for a final confrontation that would mark the end of one of South America’s most advanced and creative cultures, the end of a peaceful people who had led joyful, productive lives along this coast for more than a thousand years.

Rendering of Tairona Chief by Coricancha, Deviantart-dot-com

Toward the end of the 16th century, Spanish raids on the Tairona villages accelerated as the Grandees sought to conscript native labor for their plantations. Theft of the Tairona gold had been bad enough. The theft of their women and children was an offense for which there could be no forgiveness, so in 1599, the Tairona declared war on the men of Santa Marta, burning churches, and murdering Spanish noblemen in their homes. Retribution was swift, and it was vicious. The Tairona chiefs were sentenced to death, and most of the Tairona towns were burned to the ground. Those who were able to travel abandoned their homes, abandoned their villages, escaping into the high valleys of the Sierra Nevada, where they were taken in by their brethren, the Kogi and the Arhuaco, as well as the Wiwa and Kankuamo tribes. Those unable to make that difficult journey into the mountains were captured, and quite literally worked to death on the encomiendas.

There were as many as 100,000 Tairona when the first Spanish sails appeared on their horizon. By the middle of the 17th century, every last one of them was gone. Those not killed outright by the sword or the lash were felled by the diseases imported from Europe on the filthy, rat infested ships: smallpox, influenza, syphilis; diseases for which the Tairona had no natural resistance. Whole families, entire clans were wiped out in the space of a fortnight, and the contagion spread, from house to house, and village to village. Those that fled to the mountains were absorbed into those smaller tribes, finding refuge among people who shared their language and the core elements of their religion. Isolated in their mountain strongholds and fiercely private, the tribes of the Sierra Nevada have successfully avoided most contact with the outside world for more than 400 years, and they remain essentially unassimilated by contemporary Colombian society. What of the Tairona? The Sons of the Jaguar never actually disappeared. Remnants of the their culture still exist, and will always exist in the legends and traditions of those isolated mountain tribes.

Photo of Kogi Mamo © Alexander Rieser

The Kogi and Arhuaco Mamos, holy men, are powerful mystics, selected at birth and trained from a very young age, commiting to memory the oral traditions that have been passed down through more generations than anyone can count. For them, the Tairona war with the Spaniards was a recent event in their collective, ancestral memory, and they can speak of things that transpired during those times as if they happened a month ago. They can tell you that the villages on the coast were the first to be abandoned by their elder brothers. The Tairona warriors, fierce though they may have been, had no defense against an enemy that came at them from the sea, firing cannons that crushed their homes and meeting houses, killing women and children who should have had no part in the fight. Half of their people were already dead or dying from the sickness. Leaving everything behind was hard, but it was the only sensible thing they could do.

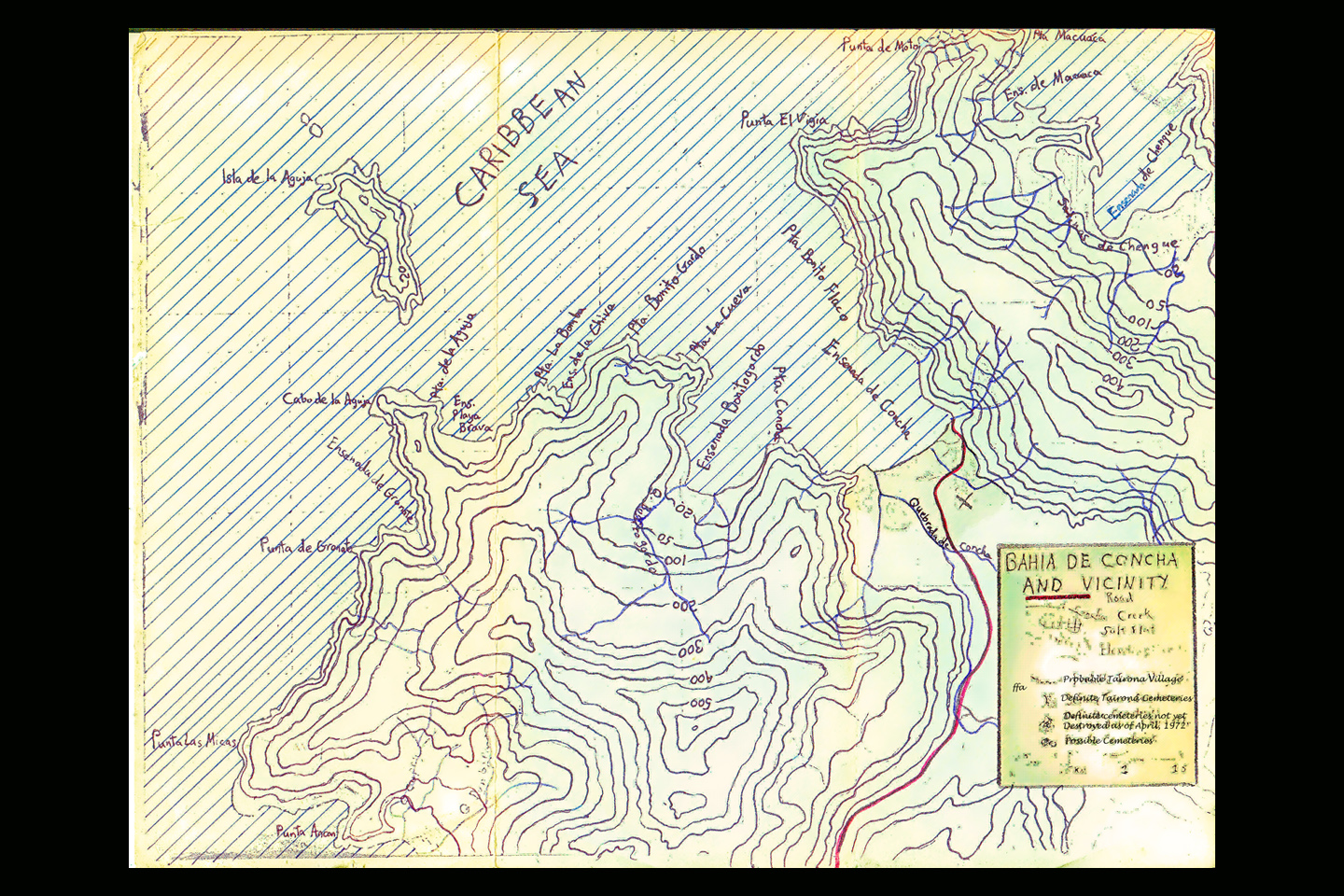

Concha Bay was the site of one of those abandoned coastal villages, Before the Spaniards arrived, it was an important Tairona chiefdom, a prosperous community, with well-watered crop land in the valley and a bountiful supply of fish in the bay, which they captured very efficiently, using nets weighted with stone sinkers. There was continuous trade with the other Tairona towns, and religious observances that unified the people with a powerful, animistic belief system. Concha Village consisted of more than 100 circular dwellings, with stone foundations and thatched roofs, connected by walkways paved with stone. Each dwelling was home to an extended family, with ownership passed down through the mothers. The finest building was the men’s house where the meetings were held, decorated with beautiful weavings, tapestries, and stone carvings representing clan totems. All of that was left behind when they fled, as they took only what little they could carry. When the Spaniards arrived and found them gone, they ransacked the empty town in a search for gold, literally tearing the place apart. They burned what was left, and when they were done, nothing at all remained of the village at Concha Bay. Within ten years, the charred stones, the paved walkways, the irrigated fields, all of it was swallowed by the tropical forest, the bosque espinoso tropical.

The rainy seasons followed the dry seasons in an endless progression,..

…and in that manner, four centuries passed.

After the Tairona were defeated, the land grant that included Bahia Concha was divided, and subdivided, changing ownership any number of times, until, by the mid-20th century, the best part of the beach and the land behind it had been passed down to Don Julio Sanchez Trujillo, the scion of one of the oldest Santa Marta families. Traditional uses of the property included a papaya farm, large stands of bananas, and free ranging cattle that grew fat, grazing in the forest. When the Tayrona National Park was established in 1964, plans called for the annexation of Concha Bay into the preserve, since it was part of the larger ecosystem they intended to protect, but Julio Sanchez had some influence with the courts, and his rights as a property owner were respected.

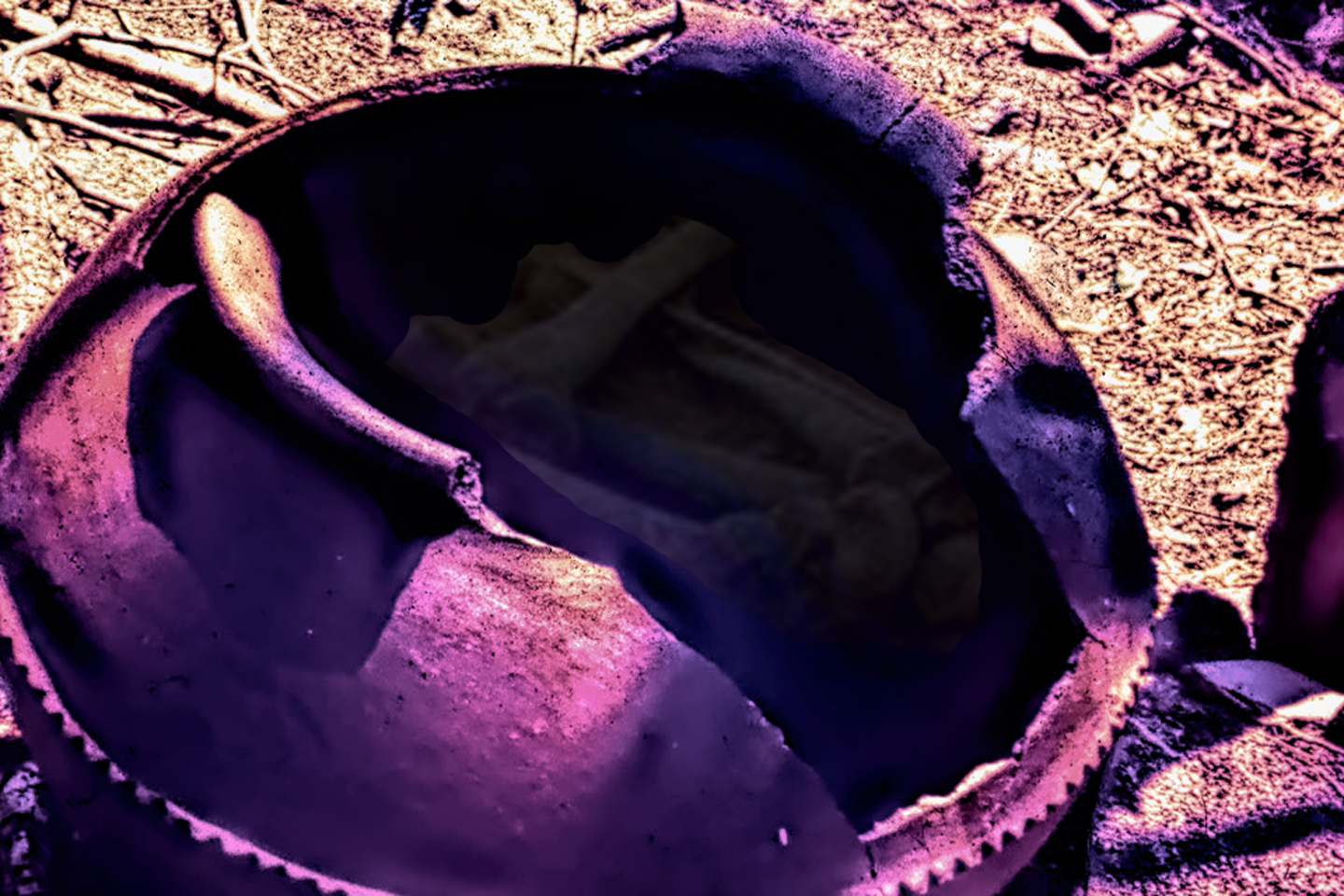

No one knew for certain what impact the establishment of the Tayrona National Park would have on the Santa Marta area, but it seemed a safe bet that there would be an increase in tourism, Don Julio wanted to cash in on the potential boom, but all he had to offer at Bahia Concha was an empty beach, and the only way to get to his beach was a rough dirt track. If he was going to attract tourists, he needed a better road, and some cabins on the beach, and a restaurant serving up fresh fish and cold beer. He thought up a name for the place: Balneario de Villa Concha, the “Villa Concha Resort and Spa.” Then he hired a crew to build the road, using a bulldozer leased from a construction company. As the new road progressed toward the beach, the soil became very sandy, so the work went more quickly, until the foreman suddenly called a halt. The blade of the bulldozer had run into something under the surface. Plowed off to the side with the rocks and the roots there was a large amount of pottery, including a big clay urn that had cracked open. Inside the urn, there were bones. Human bones.

They delayed for a day while they brought in an expert from Santa Marta, a guaquero, a professional tomb robber named Alvaro Gomez. The guaquero confirmed what the foreman already suspected: the bones in the urn weren’t anything to worry about. They were merely Indian bones, Tairona bones. It would seem that the bulldozer had plowed smack into the middle of a Tairona cemetery, hundreds of years old. The guaquero admonished them to be careful with this section of their road. Not out of respect for the dead, surely, but out of respect for the pottery, which was worth money if they could manage to avoid smashing it, To that end, men with shovels walked ahead of the bulldozer, probing the sandy soil, and unearthing hundreds of ceramic artifacts, including more of the big burial urns, which contained, in addition to crumbling bones and leering skulls, beautifully carved stone jewelry, and gold! There were nose rings, ear rings and other jewelry, along with extraordinary cast gold figurines. The workmen were laborers, one step up from dirt poor, and the gold got them so excited they nearly came to blows, arguing over who should get to claim these things. The excitement lasted three full days as they cleared all the urns and other artifacts from the path of the road, but after a distance of about half a kilometer, as the crew came close enough to the ocean to smell the salt breeze, the pottery below the surface petered out. The rest of the project was completed without further incident, but there were two dozen workers on that road crew, so in no time at all, the word spread like wildfire about the Tairona cemetery, and the golden treasures in those Indian graves.

Julio Sanchez didn’t really care about any of that; he was much more interested in making use of his new road to build his resort. He contracted with the same firm that provided the bulldozer to have five casitas constructed among the trees that ran along the beach. They used concrete block, covered it with stucco, and put on good metal roofs that would serve well in the rainy season. The casitas were a bit rustic, but not half bad for that time and place. Each had two furnished bedrooms, a bathroom with a flush toilet and a shower, a cooking area, and a porch with a hammock. They would be available to beach loving tourists by the day, week, or month, and if he managed to keep them rented, he would build more. The open air restaurant went up quickly, along with some public restrooms. Finally, an announcement in the newspaper, and flyers posted around Santa Marta, letting the world know that the “Balneario de Villa Concha” was open for business.

In the meanwhile, Alvaro Gomez had been pestering him non-stop about that Tairona cemetery. Gomez wanted to put a crew of diggers to work as soon as possible, and he offered to split the value of any salable finds, right down the middle. Don Julio was honestly troubled by the whole business, bothered at the notion of disturbing a graveyard, even an ancient Indian graveyard, but he was a practical man. His workmen had already caught a dozen other guaqueros sneaking under his fences and digging in his fields without his permission, and there was no way to keep them out, short of armed patrols. If he granted a concession to Gomez, he would be implementing a measure of control that wouldn’t cost him a single peso, and if they actually found more gold, he stood to reap a tidy profit. He agreed to allow the digging, with the proviso that Gomez and his guaqueros stay out of the fenced off section of the bosque east of the roadway, because he was still running his cattle over there, and they might break their legs, falling into open holes.

Business was slow that first year. The casitas, as well as the restaurant, saw most of their customers on weekends, and the only time they were truly busy was on holidays. The rest of the time, the place was dead, but as for that Tairona cemetery? That overgrown plot of sandy ground couldn’t have been more alive! The site was a literal gold mine, producing valuable finds nearly every single day. Gomez wanted to add more diggers, so they could work more quickly, but Don Julio declined, preferring a slower pace. He reasoned, correctly, that the men already out there were stealing him blind, presenting no more than a fraction of their finds when it came time to divide the profits. More diggers would only mean more theft, and any increase in activity might draw unwanted attention. Best to keep it low key, because he knew, in his heart, that what they were doing was wrong.

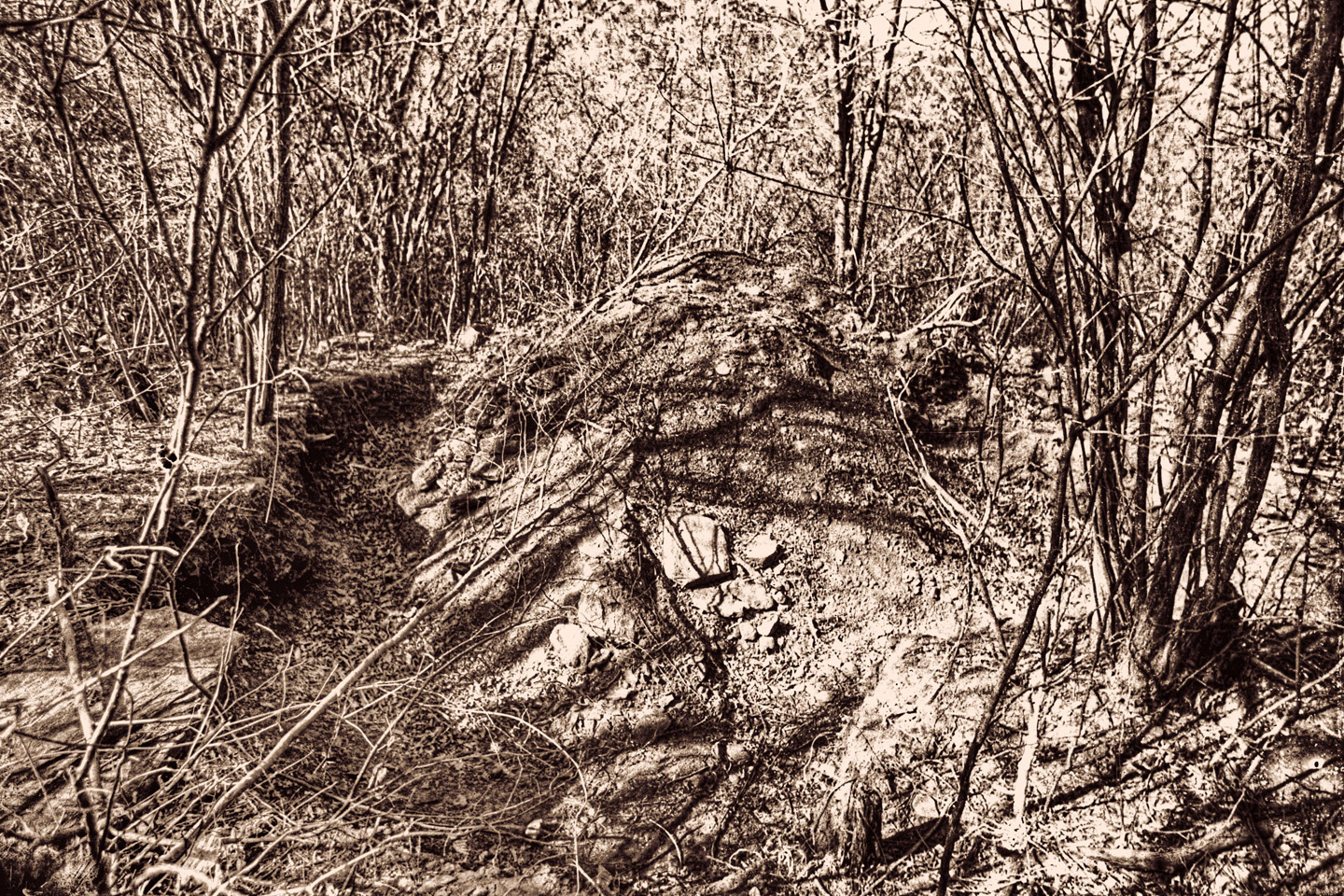

The digging went on for a year and a half, until there was no more pottery, no more burials in the section of the cemetery where Julio Sanchez allowed the guaqueros to work. They abandoned all civility at that point, and spilled into the forbidden sections of the graveyard that had never been dug. There were rich finds in that section, and all hell broke loose. Guaqueros were fighting one another, and Don Julio had lost all semblance of control. The Army was called in to stop the digging, but at that point, the Tairona cemetery at Bahia Concha, 10,000 burials representing nearly a thousand years of history, had been completely destroyed. Don Julio’s pasture resembled nothing so much as a battlefield, filled with holes that looked like bomb craters, surrounded by smashed pottery, stone metates, and scattered, broken bones, bleaching in the sun.

The gold in the Tairona graves had ritualistic importance. Gold was the blood of their mother, the earth, and the offering of gold in a burial ensured that the mother would enfold and cherish the deceased. Gold was important to the Tairona in life, as well. They fashioned beautiful things from it in honor of their mother, objects that they prized, even venerated, as the ultimate symbol of distinction in their society. It was the Tairona gold that triggered a blood lust in the Spanish invaders, ultimately causing the destruction of the entire Tairona civilization. That cycle was repeated in modern times, when the lust for Tairona gold infected the guaqueros, causing the destruction of the last refuge of the Tairona ancestors, in one final humiliation, one last indignity: the destruction, the desecration, the rape of Bahia Concha!

~~~~~~~

Many of the photographs in this slideshow (below) were shot on 35mm film, which was scanned and edited to clean up scratches and flaws in the emulsion, the result of half a century of incautious handling and less than ideal storage conditions.

Click any of the images to blow them up to full screen, with captions.

(Unless otherwise noted, all of the images in these posts are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.)

A lot of what I’ve written in this post is based on memory, because I was there on the scene when a lot of this happened. Those memories are pretty old now (as am I!), so I take full responsibility for any errors or inaccuracies. For the record: I am not an academic. The assumptions made and the conclusions drawn in these posts are those of a reasonably well-informed enthusiast; I haven’t put in the work that might make me an expert. At one time, I was up to my neck in this stuff, but the most that entitles me to is an opinion.

Questions, comments, and criticism are always welcome!

Be sure to check out the next post in this series: Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent

MORE SOUTH AMERICAN ADVENTURES:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

South America Before the Conquistadores

Tumaco: Atrocity Trumps Antiquity on the Coast of Colombia

Within a matter of a few years, every readily accessible site had been looted and stripped of artifacts. There were laws in Ecuador prohibiting trade in antiquities, but during the 1970’s, there was no such law in Colombia, so the Tumaco heritage, extraordinary in its complexity, was scattered to the four winds.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tumaco: From Out of the Flood

Far more common than the precious metal were the artifacts made of clay, small, often elaborate figurines depicting nearly every aspect of the people’s daily lives, as well as their animistic mythology. It is through those figurines, some intact, but most in fragments, that these all but forgotten people have come to be known.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

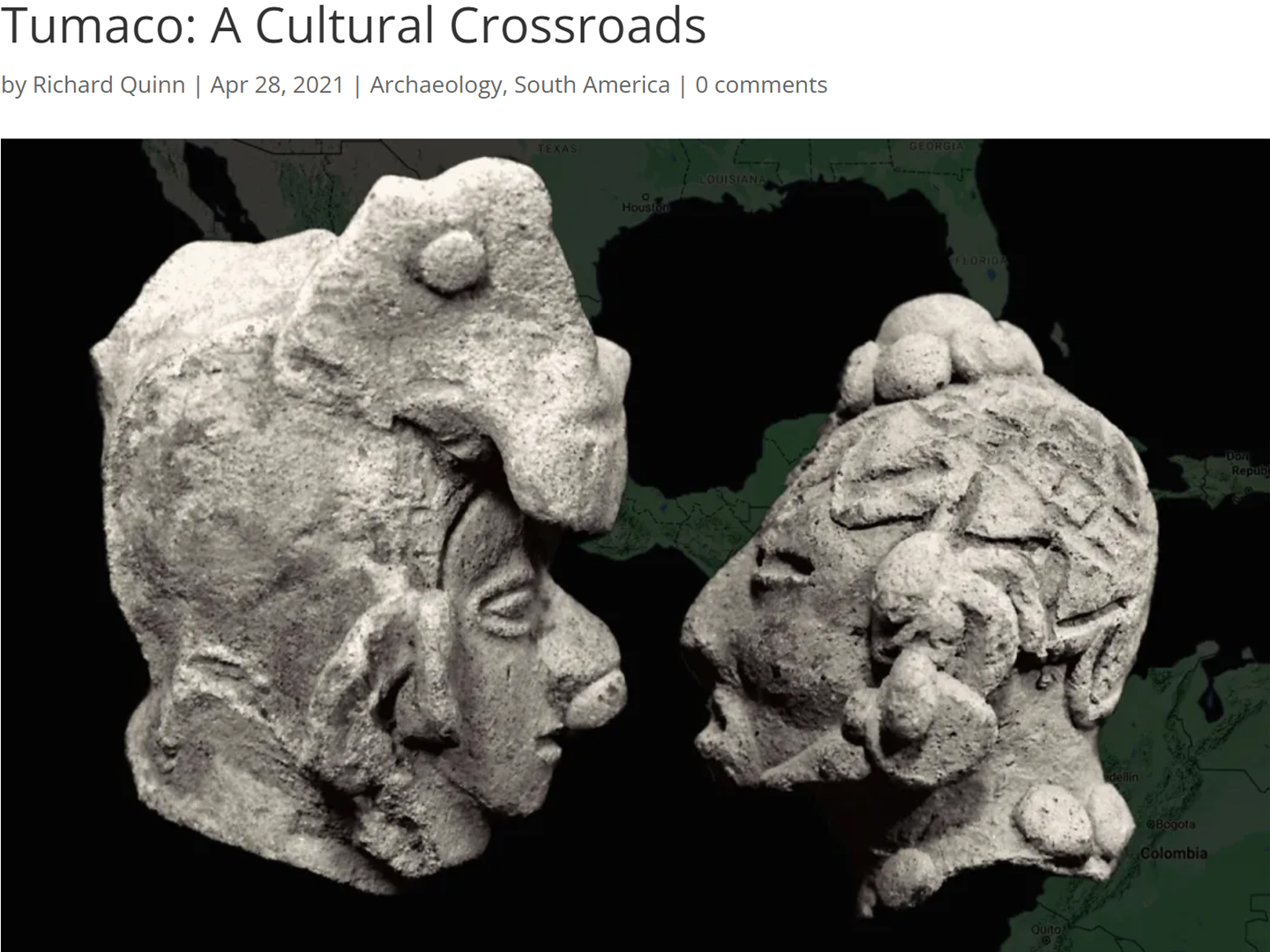

Tumaco: A Cultural Crossroads

Traders coming down from the north had to endure many days of difficult travel along a coast that’s tough to negotiate even today. The reward must have been worth the trouble, because men from the Yucatan did, in fact, make that journey, trading goods, as well as ideas with the men of Tumaco.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

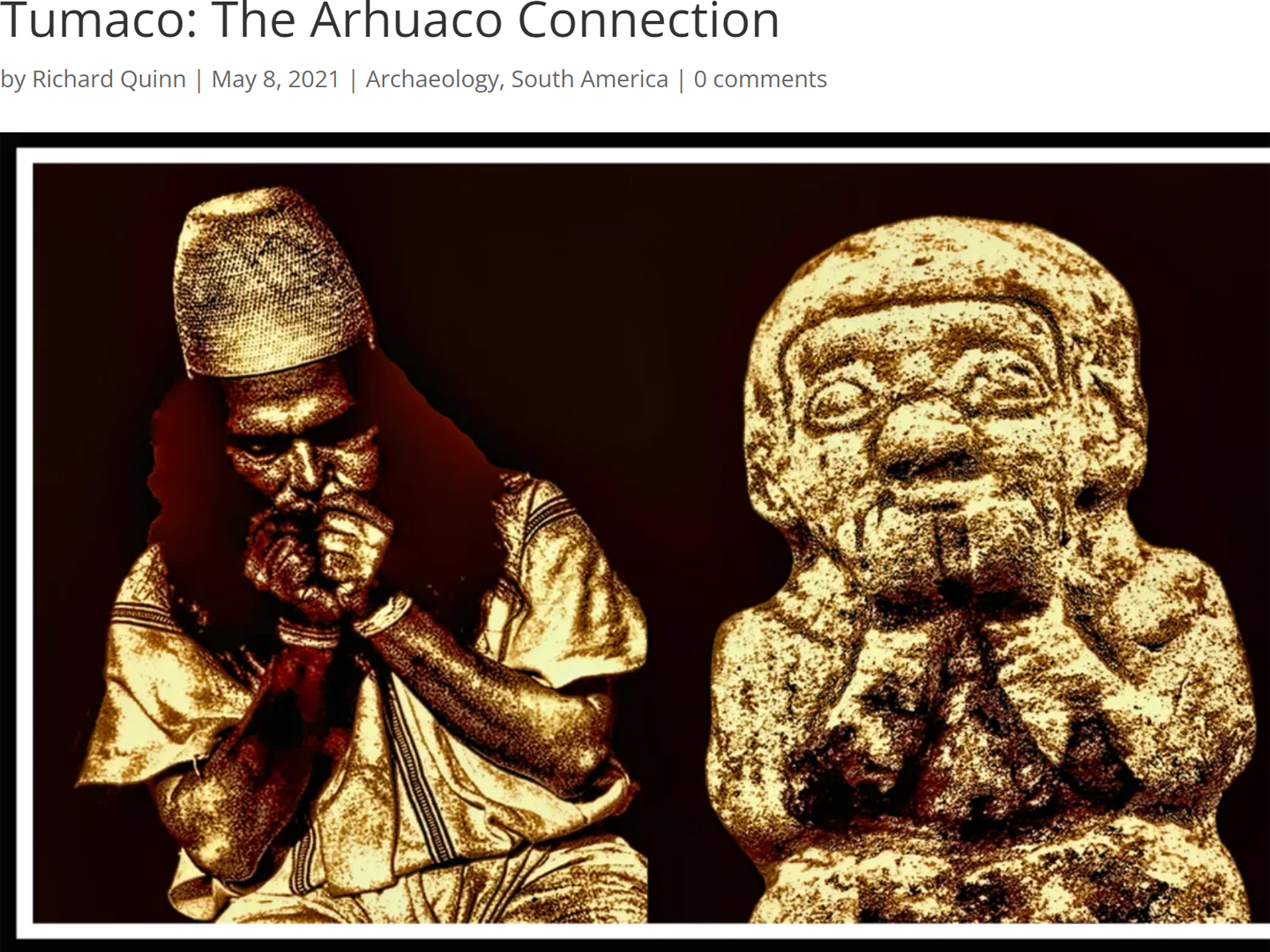

Tumaco: The Arhuaco Connection

What we really know of history is like an ancient tapestry, worn, and threadbare, with missing patches confusing the grand design. When we make a new connection, we restore a missing thread, and little by little, thread by thread, we fill in those troublesome blanks.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

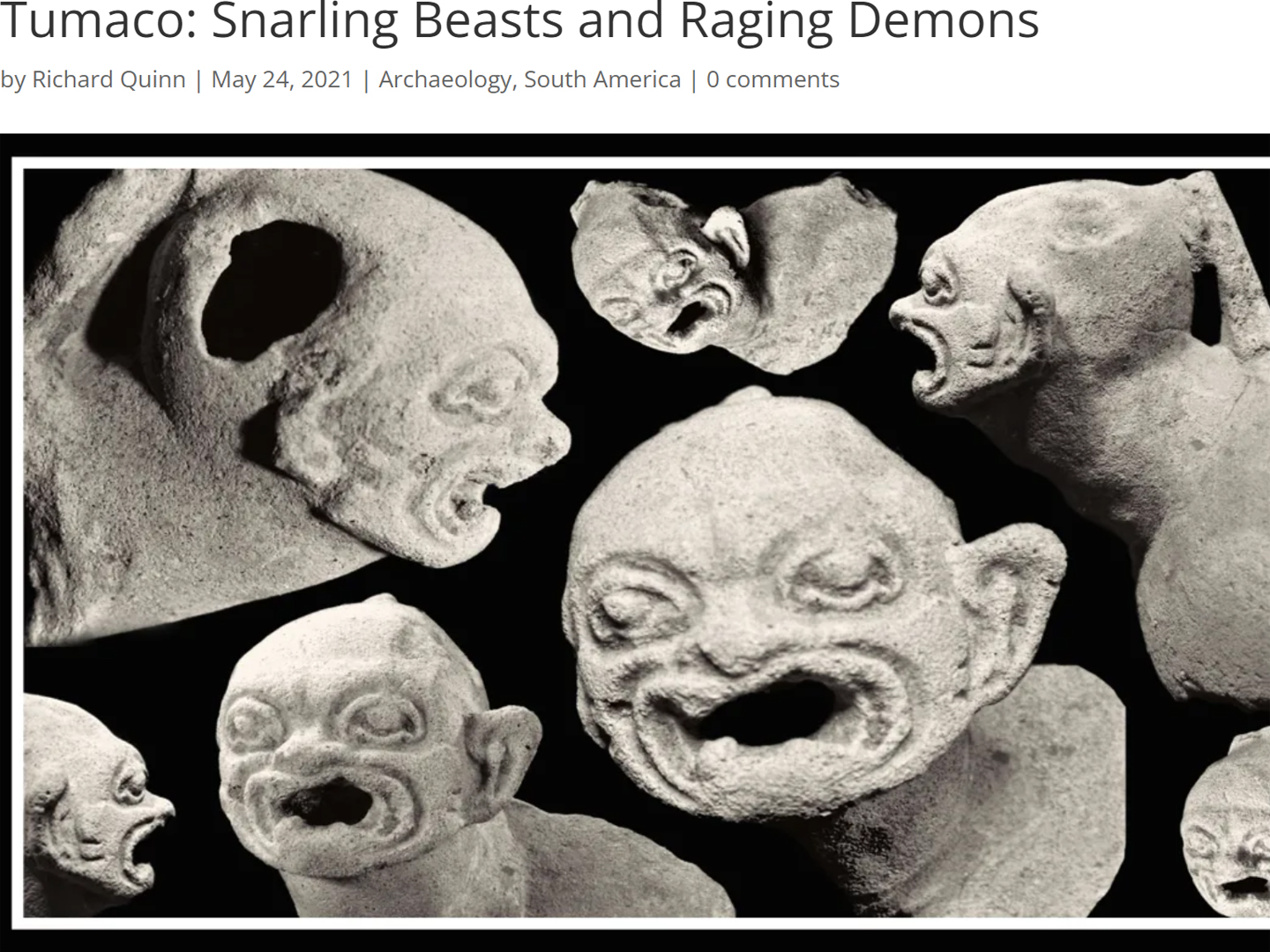

Tumaco: Snarling Beasts and Raging Demons

There was so much ancient pottery in the Tumaco area that it literally washed up out of the ground after every big rain. With so many men out there looking for gold, it was impossible NOT to find Tumacan ceramics. Strange figurines and fragmented sculptures, unlike anything that had been found before, anywhere else in Colombia.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

In the Vale of the Stone Monkeys: Peril and Petroglyphs in the Colombian Jungle

El Manco was easy to spot; he had embraced his defining handicap, a right arm that had been severed above the elbow, and that wasn’t even his only problem. He was also missing his right eye, nothing there but an empty socket and an ugly knot of scar tissue. “Tough old bird” doesn’t begin to describe a hardscrabble character like Manco; he had a face with creases like a roadmap straight to his own personal version of hell.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Rape of Bahia Concha

It was the Tairona gold that triggered a blood lust in the Spanish invaders, ultimately causing the destruction of the entire Tairona civilization. That cycle was repeated in modern times, when the lust for Tairona gold infected the guaqueros, causing the destruction of the last refuge of the Tairona ancestors, in one final humiliation, one last indignity: the RAPE of Bahia Concha!

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent

Paul dug with his hands then, finally sticking his arm into a hollow space, pulling out a dark object. Grinning at me from the bottom of his hole, he handed up what he’d found. A round blackware vessel representing a coiled serpent, open in the middle, with a spout at the top of the head. I’d seen a lot of Tairona artifacts, but I’d never seen anything remotely like that one.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments