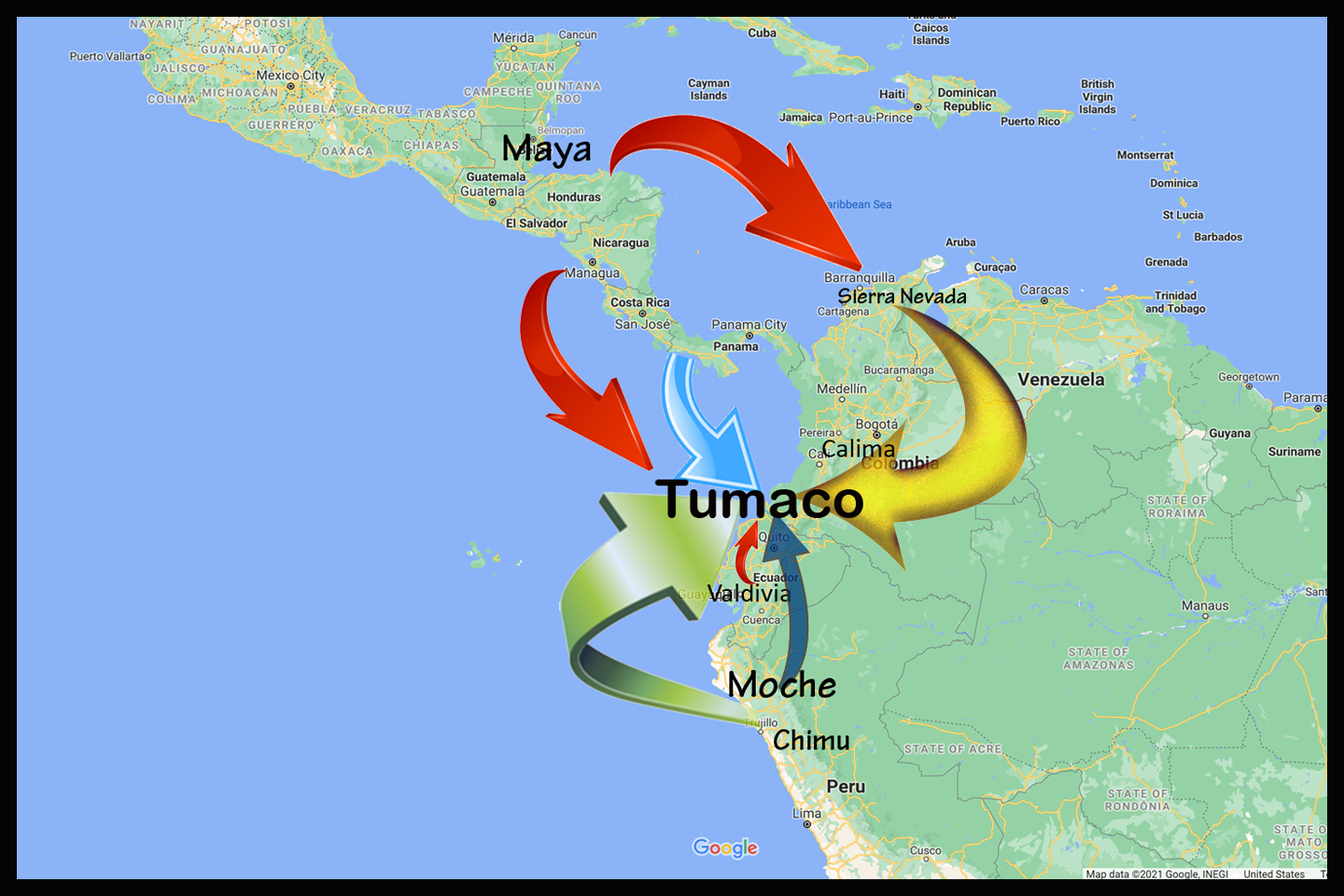

They didn’t originate the techniques that they used in creating their art; they simply improved upon processes they learned from other, older societies that inhabited coastal areas to the south, and to the north. In the Americas of that era, a hodgepodge of disparate cultures had developed, each with its own unique language, style of dress, customs, mores, and traditions. Populations of varying size were isolated from one another by mountains, jungles, deserts, and oceans, but there was still contact among them, extending to even the most far-flung outposts. The primary mechanism of that contact was trade: trade in goods, tools, and technology, as well as trade in ideas.

In mountainous areas, traders traveled on foot, braving steep trails, rushing rivers, and sometimes hostile natives, hauling high value goods such as salt and obsidian, limited to what they could carry on their backs.

Traders along the coasts had it much easier, traveling in shore-hugging canoes that could carry much more weight, over much greater distances. Canoes could accommodate bales of valuable produce, such as cacao, coca, and seed for maize agriculture, as well as hand-crafted goods, such as woven textiles, carved beads, and ceramics. The Maya in Central America are known to have established extensive coastal trading networks throughout their territory and beyond, spreading their jaguar cult along with their trade goods, everywhere they went. The Moche people, on the desert coast of Peru traded and fought their way throughout the region, their unmistakable cultural influence extending far and wide, while the Valdivians on the coast of Ecuador developed pottery-making techniques that ultimately spread to everyone else, beginning almost 3,000 years before the Christian era.

Trade routes followed the patterns of human settlement, and in that regard, the villages of Tumaco were ideally situated. The area north of their territory was a region of dense jungles and mangrove swamps, hemmed in between the coastal mountains and the Pacific Ocean; a no-man’s land where the rain never stops falling. For coastal traders coming up from the south, Tumaco was the last vestige of civilization before entering that tangled nightmare, and for any brave explorers coming down from the north, Tumaco was the first thing they came to when they finally emerged from it. Overland trails from the Andes funneled down to Tumaco as well, along the same route followed by the only modern road.

As an example: the double spout and bridge vessel on the left (below) is from the coast of Peru, and it is a functional ceramic bottle for drinking water, first developed by the Paracas culture, and refined by the Nasca, who made this one. The bridge serves as a handle. Water pours from either spout, while the opposite spout acts as a vent.

In the example on the right (above), the Tumacos adapted the form, but not the function. This thick-walled, flat-bottomed figurine of a seated elder was created purely for display, as it would not have held enough water to be useful as a drinking vessel. Even without the benefit of scientific excavation and proper dating of the Tumaco artifact, we know that the concept, the double spout and bridge vessel, is an idea that developed in the south, and arrived later in Tumaco, most probably brought by traders.

There are countless examples of similarities between the ceramic art of Tumaco and that of the other pre-Hispanic cultures of Ecuador, such as the Jama-Coaque and the Bahia, who occupied territories to the south of Tumaco, as well as the Moche and Chimu cultures, further along, on the coast of Peru. Trade coming up from the south through this area is easy to visualize, and it was easy to accomplish along that relatively easy shoreline. Traders coming down from the north, on the other hand, had to endure many days of difficult travel along a coast that’s tough to negotiate even today. The reward must have been worth the trouble, because men from the Yucatan did, in fact, make that journey, trading goods, as well as ideas with the men of Tumaco.

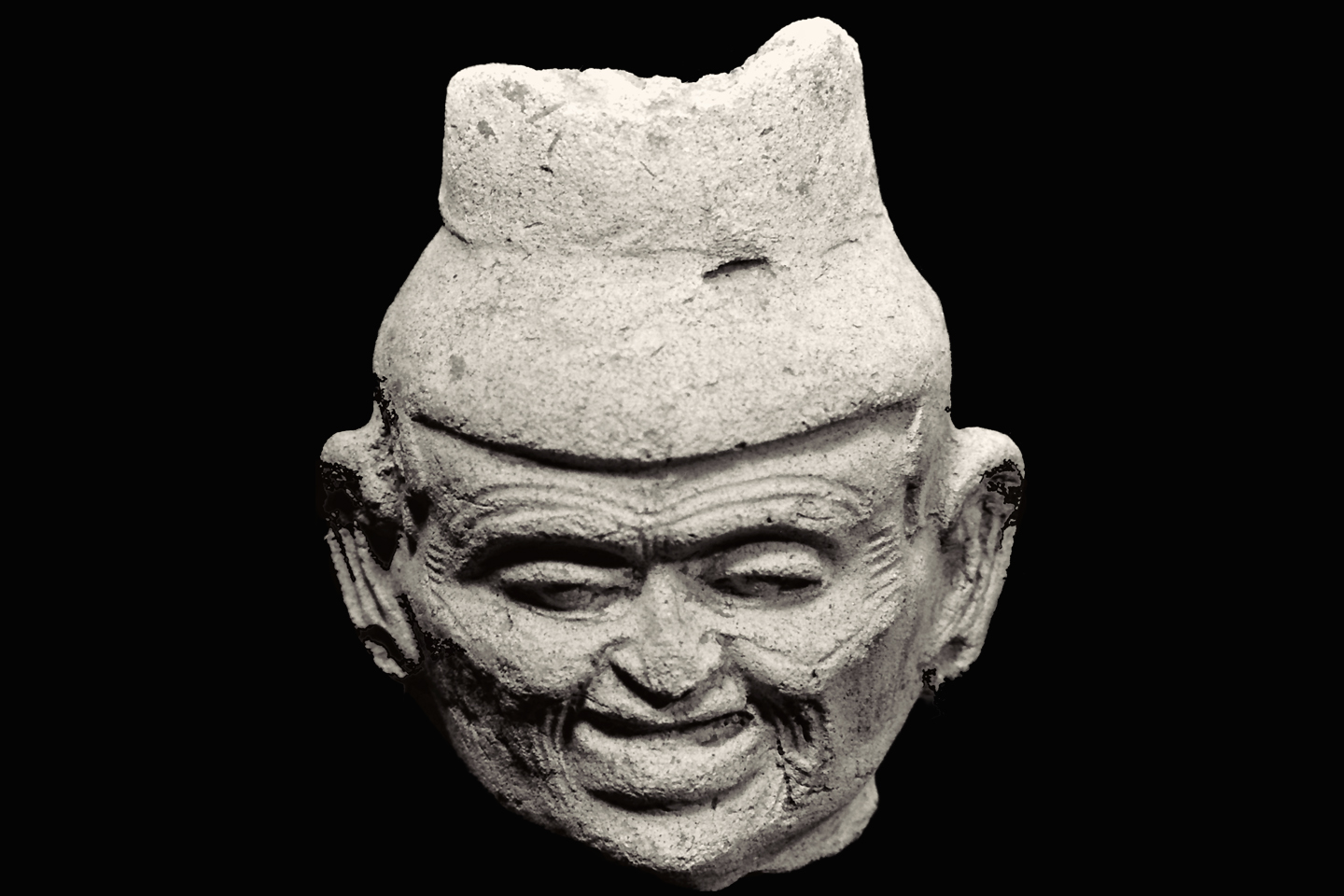

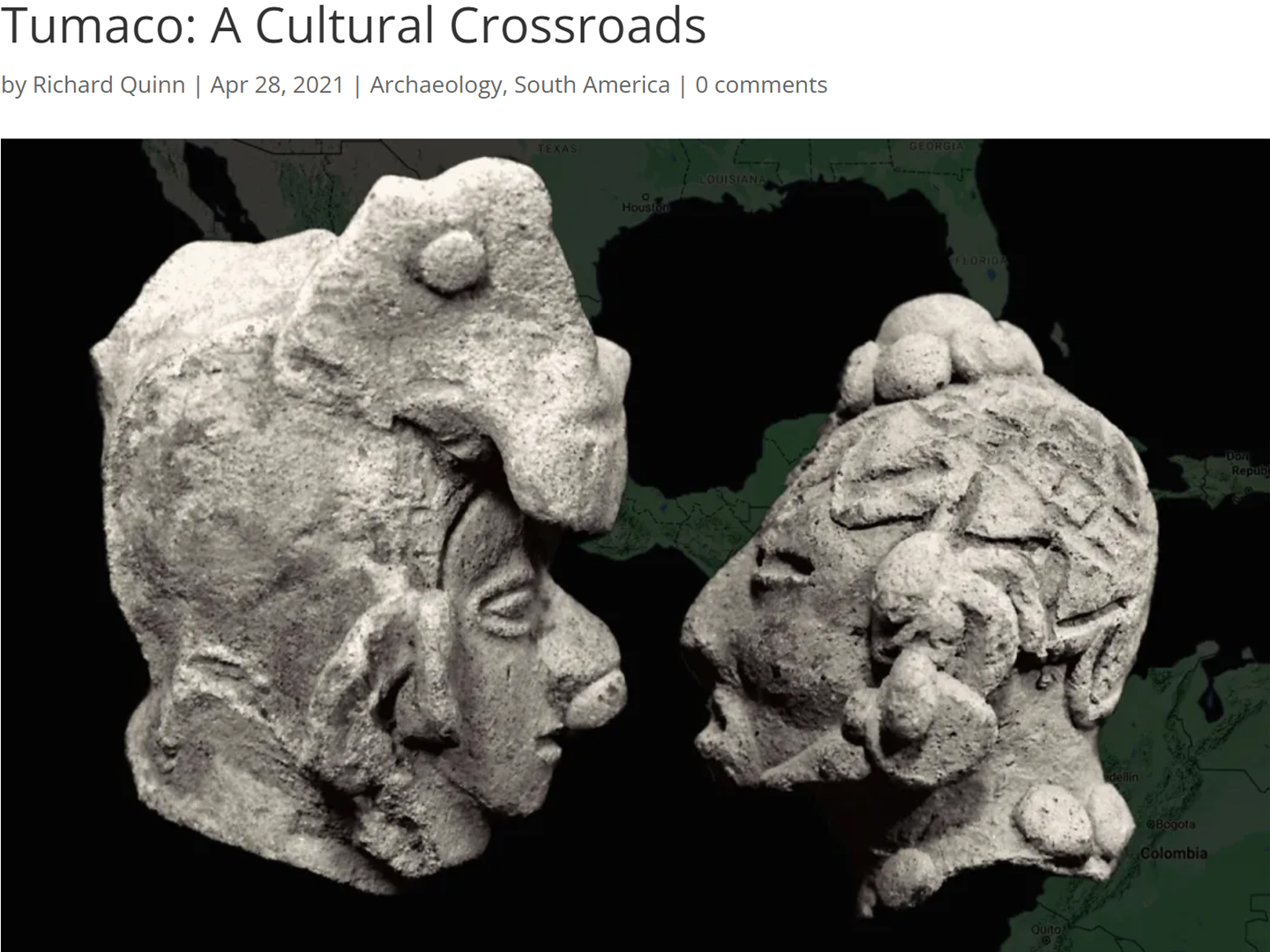

Below are two heads, broken from figurines recovered in Tumaco.

Along with that seed corn, one of the most powerful concepts carried south by traders from Mexico was the worship of Ek Balam, the Jaguar deity:

The picture on the left (below) is of a large stone carving found at a Mayan site near Guatemala City. The image on the right is a fragment of a ceramic mask unearthed near Tumaco. They are not all that similar in style, or in execution, but they are both undeniable representations of the Jaguar, the most powerful animal in the jungle, and we do know that the Jaguar cult originated in the jungles of Central America.

Like the Tumacos, the Mayans created highly detailed ceramic figurines representing aspects of their lives and their religion. The relatively simple figurine on the left (below) is from Jaina Island, an important Maya site in the Gulf of Mexico, near Campeche. The figurine on the right is from Tumaco, on the Pacific coast of Colombia, and almost 2,000 miles away. Finding the similarities doesn’t require any imagination. Figuring out how it all fits together? That’s another story altogether.

The development of pottery making in Ecuador can be traced back to the Valdivia Culture on the southern coast, where they found some of the earliest examples of pottery making in all of South America, dating to 3,000 B.C. Funny thing about it, there wasn’t a lot of trial and error. The oldest samples were already using techniques that would have been considered advanced in other parts of the world, something the researchers found very odd.

A theory was proposed, a story, if you will, involving a boatload of Japanese fishermen blown far off course and cast adrift by a typhoon. Prevailing ocean currents might well have taken this hypothetical boatload of fishermen all the way to the southern coast of Ecuador, where the survivors might well have been taken in by the natives; the Valdivians. The men from Japan might then have taught their hosts a few tricks from their home country—such as, how to turn clay into pottery? Styles and techniques that were in use by the Jomon culture in Japan in 3,000 B.C. are a pretty good match for the styles and techniques that simply appeared at about that time in southern Ecuador.

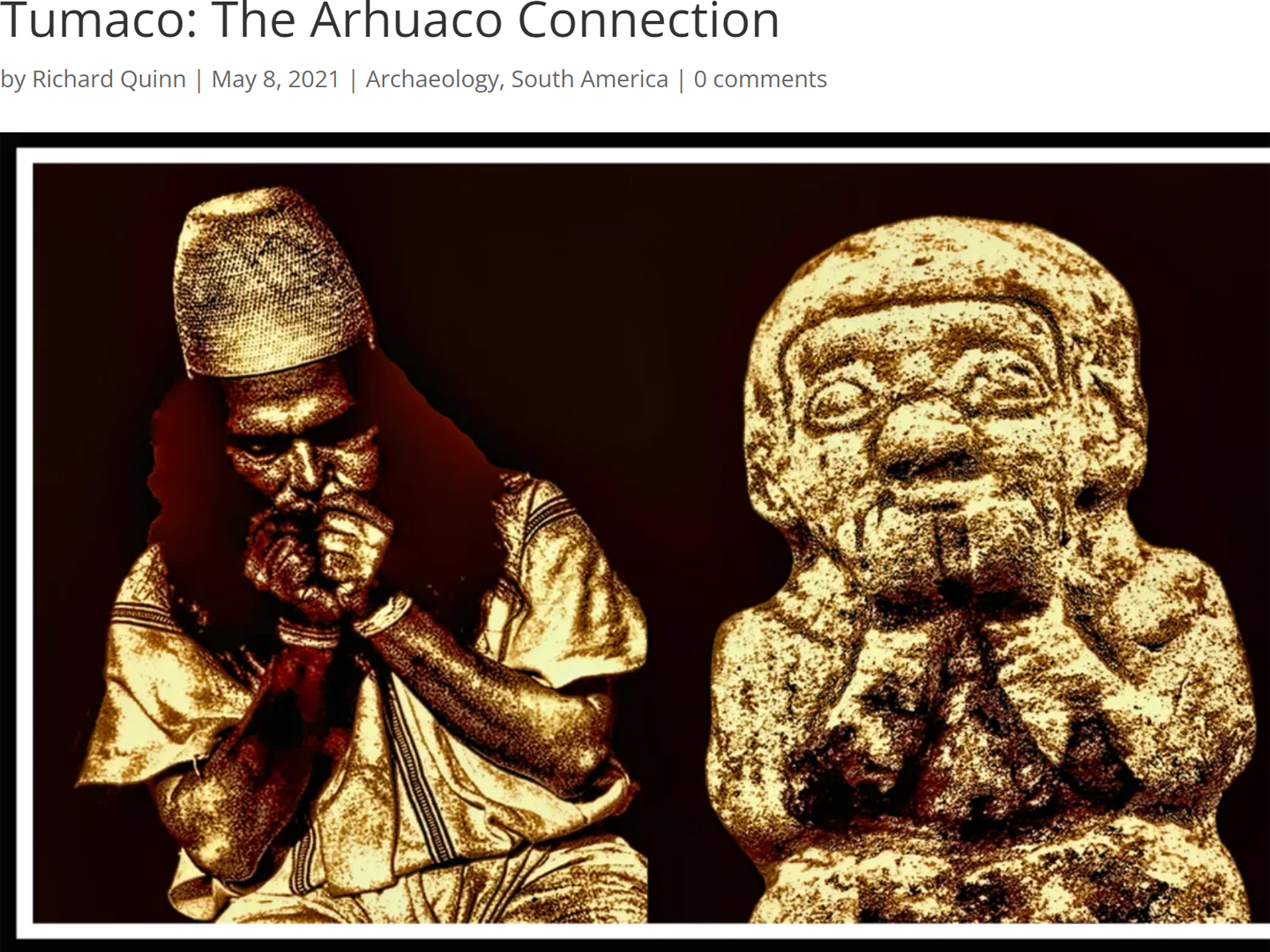

This figurine from Tumaco (below) has nothing to do with any of that, but it does look decidedly oriental. Zoom in on the photo, and examine it closely: it’s a man, with oriental features, and some serious muscles in his arms. And wait—what’s that he’s wearing as a necklace? An upside down skull?

~~~

Unless otherwise noted, all of the images on this site are my original work and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

Click any photo in the slide show to expand the images to full screen, with captions:

MORE SOUTH AMERICAN ADVENTURES:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

South America Before the Conquistadores

Tumaco: Atrocity Trumps Antiquity on the Coast of Colombia

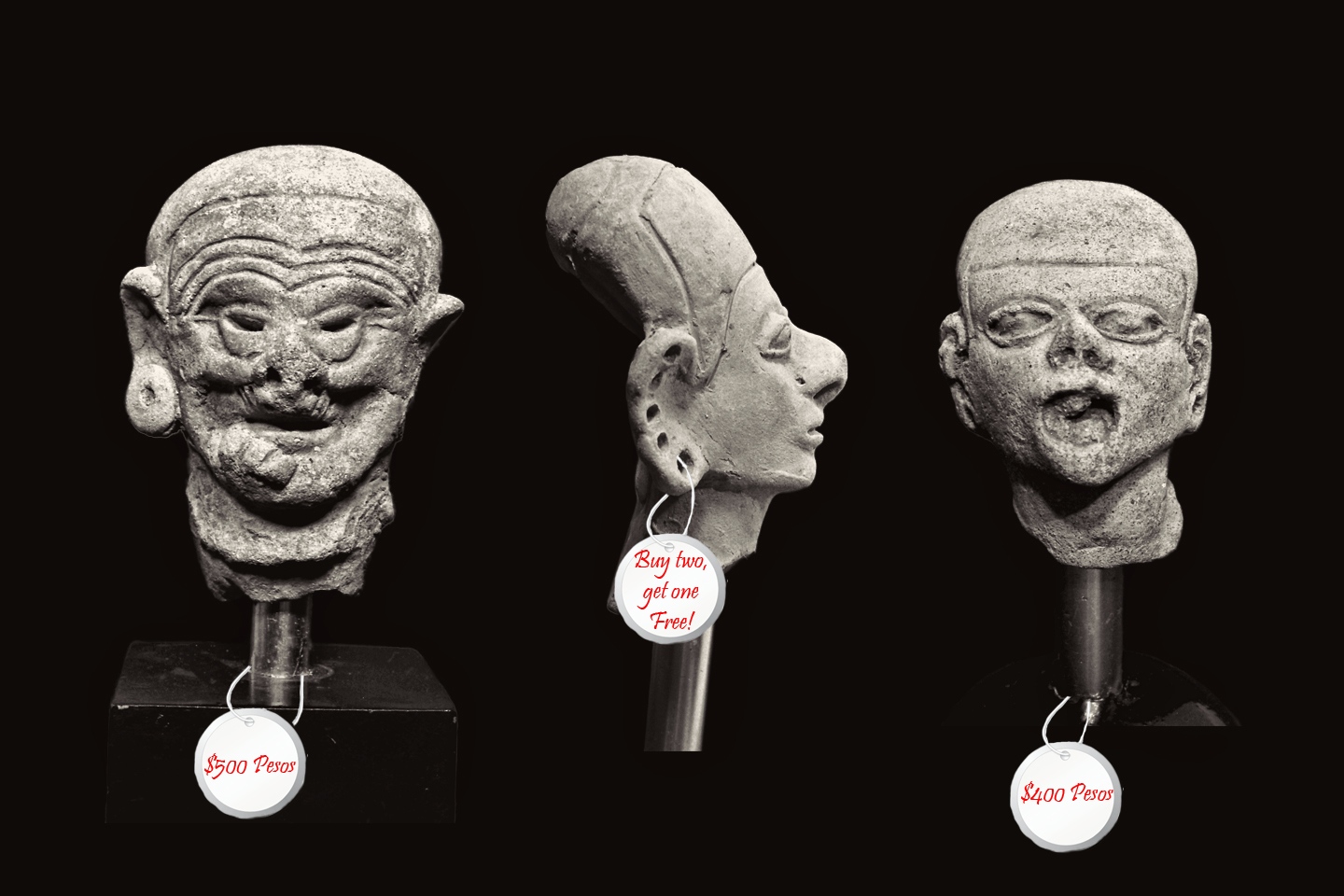

Within a matter of a few years, every readily accessible site had been looted and stripped of artifacts. There were laws in Ecuador prohibiting trade in antiquities, but during the 1970’s, there was no such law in Colombia, so the Tumaco heritage, extraordinary in its complexity, was scattered to the four winds.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

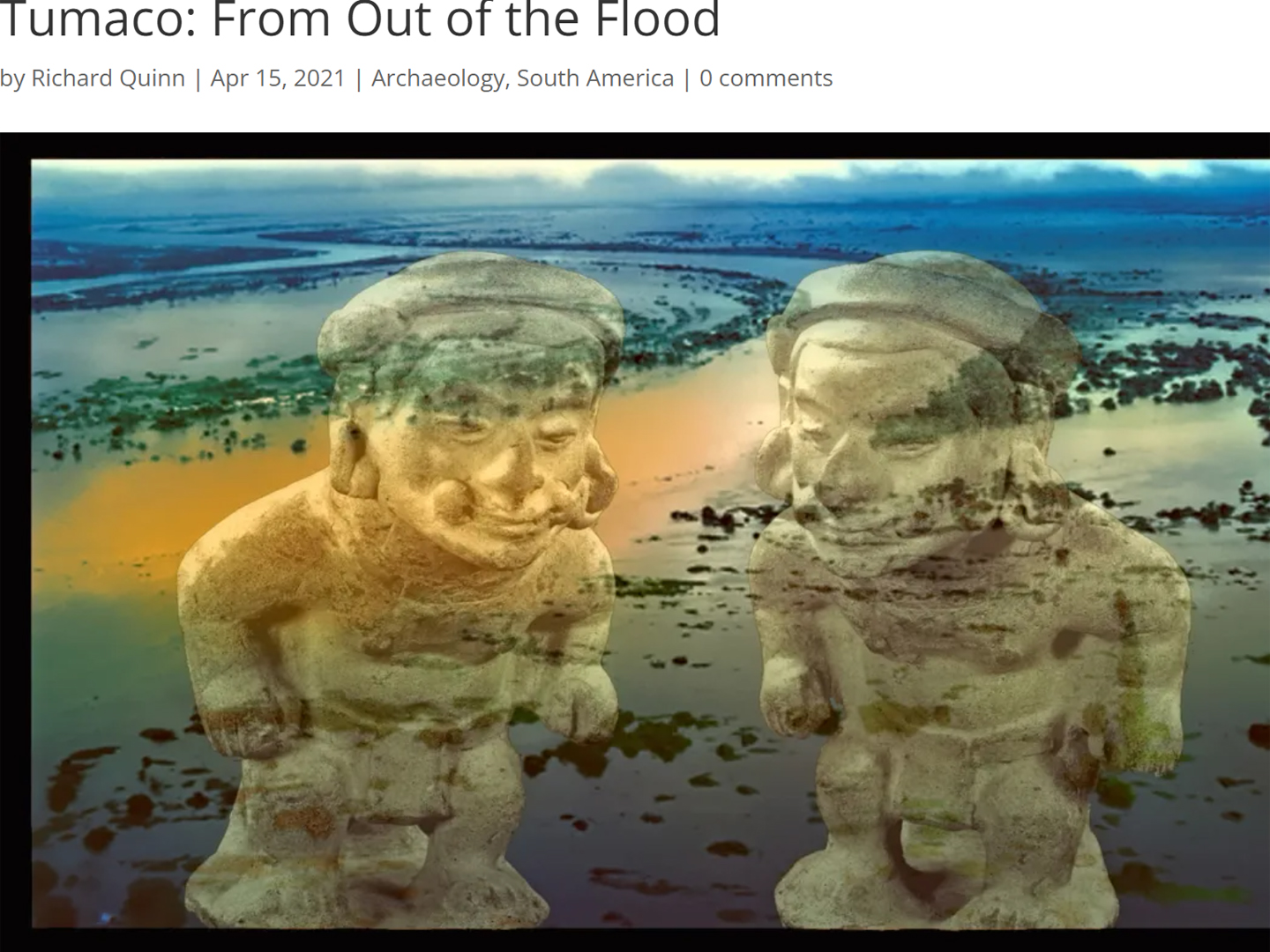

Tumaco: From Out of the Flood

Far more common than the precious metal were the artifacts made of clay, small, often elaborate figurines depicting nearly every aspect of the people’s daily lives, as well as their animistic mythology. It is through those figurines, some intact, but most in fragments, that these all but forgotten people have come to be known.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tumaco: A Cultural Crossroads

Traders coming down from the north had to endure many days of difficult travel along a coast that’s tough to negotiate even today. The reward must have been worth the trouble, because men from the Yucatan did, in fact, make that journey, trading goods, as well as ideas with the men of Tumaco.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tumaco: The Arhuaco Connection

What we really know of history is like an ancient tapestry, worn, and threadbare, with missing patches confusing the grand design. When we make a new connection, we restore a missing thread, and little by little, thread by thread, we fill in those troublesome blanks.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tumaco: Snarling Beasts and Raging Demons

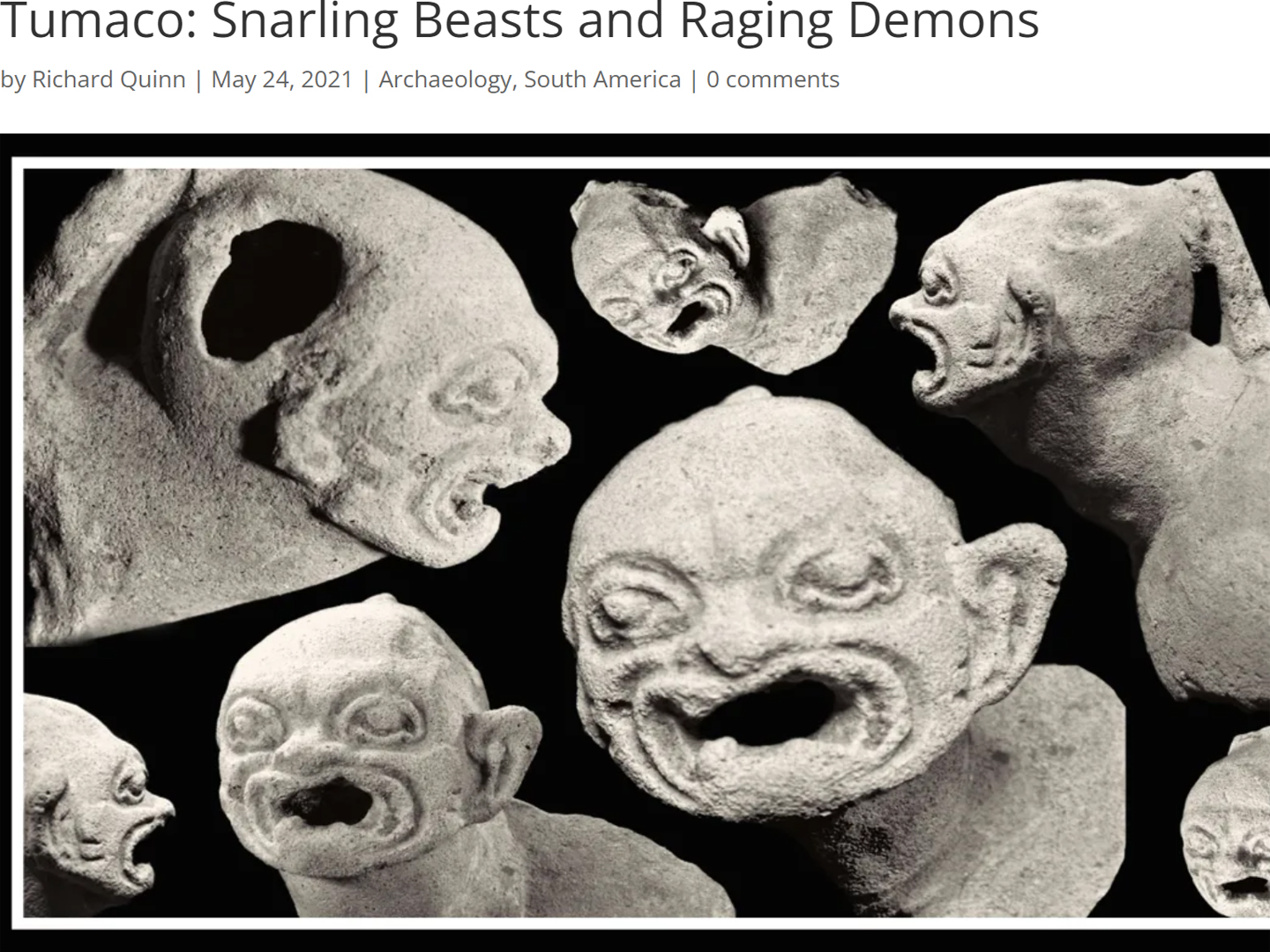

There was so much ancient pottery in the Tumaco area that it literally washed up out of the ground after every big rain. With so many men out there looking for gold, it was impossible NOT to find Tumacan ceramics. Strange figurines and fragmented sculptures, unlike anything that had been found before, anywhere else in Colombia.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

In the Vale of the Stone Monkeys: Peril and Petroglyphs in the Colombian Jungle

El Manco was easy to spot; he had embraced his defining handicap, a right arm that had been severed above the elbow, and that wasn’t even his only problem. He was also missing his right eye, nothing there but an empty socket and an ugly knot of scar tissue. “Tough old bird” doesn’t begin to describe a hardscrabble character like Manco; he had a face with creases like a roadmap straight to his own personal version of hell.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Rape of Bahia Concha

It was the Tairona gold that triggered a blood lust in the Spanish invaders, ultimately causing the destruction of the entire Tairona civilization. That cycle was repeated in modern times, when the lust for Tairona gold infected the guaqueros, causing the destruction of the last refuge of the Tairona ancestors, in one final humiliation, one last indignity: the RAPE of Bahia Concha!

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent

Paul dug with his hands then, finally sticking his arm into a hollow space, pulling out a dark object. Grinning at me from the bottom of his hole, he handed up what he’d found. A round blackware vessel representing a coiled serpent, open in the middle, with a spout at the top of the head. I’d seen a lot of Tairona artifacts, but I’d never seen anything remotely like that one.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments