MARCH 2024: Note that the information in this post has been significantly revised, updated, and expanded into a 14 part series, complete with hundreds of photographs. The series is still a work in progress, but quite a lot has been completed, so you might want to check it out, beginning with:

OR: Feel free to continue with the old version:

Update: In most parts of Mexico, the overall security situation is essentially unchanged from what I describe in this post, which was written in December of 2015. Sadly, there are a few areas where cartel violence has escalated, and the situation has deteriorated, prompting the U.S. Department of State to revise their security assessment of six specific Mexican ‘Estados’. The following regions have been downgraded from Category 3 (“defer non-essential travel”), to Category 4: Do Not Travel! This is the most extreme category of advisory, generally reserved for war zones and other areas where the rule of law has broken down and travelers are at significant risk. Today’s updated State Department advisory strongly cautions travelers as follows:

Do not travel to:

- Colima state due to crime and kidnapping.

- Guerrero state due to crime.

- Michoacán state due to crime and kidnapping.

- Sinaloa state due to crime and kidnapping.

- Tamaulipas state due to crime and kidnapping.

- Zacatecas state due to crime and kidnapping.

Always check for the most current information before planning any Mexican Road Trip. The U.S. State Department’s Mexico Traveler’s Advisory is a good resource. Note that the information above was reaffirmed as recently as March 19, 2024.

*****************************

Mexico gets a bad rap these days, and it’s not entirely undeserved. Almost anyone you ask will tell you that it’s a dangerous place to visit, especially if you’re traveling by car. The country is rife with corruption and violent crime, the roads, especially the secondary roads, are in terrible condition, and traffic laws are widely ignored, leading to serious vehicular chaos in the cities and larger towns. If you read the current traveler’s advisories issued by the U.S. Department of State, you’ll note that all six of the Mexican “Estados” that form the border with the U.S. are considered unsafe for travel. At best, you are to exercise extreme caution, drive only on major highways, and never travel at night. At worst, you are advised to defer nonessential travel altogether. That’s a deal breaker for the average tourist: it’s impossible to drive to the interior of Mexico without first passing through one or more of those border states. Worse: assuming you do make it through without incident? You’ll have to make the same risky run a second time, in reverse, in order to get home again!

That may have sounded a little sarcastic, but really, I’m not making light of any of this–it’s deadly serious. Northern Mexico is like a war zone, the war in question being the decades old war on drugs. The area is quite literally a battleground, where cartel thugs shoot it out with Mexican law enforcement, as well as with each other, for control of insanely lucrative smuggling routes. These guys hold their turf with violence, and that violence sometimes intersects the trajectories of innocent, ordinary people. On more than one occasion, American tourists have been caught in the crossfire, or even targeted, usually for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, so the State Department’s warnings advising against non-essential travel through vast sections of the border region are entirely justified. However: just like with anything else, the actual risk is relative. I would never tell anyone to downplay the State Department’s Travel Advisories. What I would ask you to do is to really read them, the whole text, not just the highlights, and to balance what they say with recent, first-hand information (things like this blog). Touring Mexico by car is challenging. There are risks, there are aggravations, and there are many, many things to watch out for. Ah, but there are also great rewards!

The Border

Are you still interested? Really? Okay, here’s how it works: Your first step, when planning an excursion by car into Mexico, is to choose your border crossing. There are no less than 50 legal crossing points on the 2,000 mile long U.S. Mexico border, but they are most definitely not all created equal, and there are some that will serve your purposes better than others. The route that takes you most directly from your starting point to your destination is the ideal, but there are some stretches of highway you’ll want to avoid, even if it means going out of your way. That’s why it’s so important to seek out current information on road conditions and public safety concerns–in advance, not after the fact, and to look for official sources (like the US Department of State), as opposed to anecdotal comments posted on travel forums.

Before you do cross the border, at whichever crossing you use, you should purchase your Mexican auto insurance. You can buy it online in advance of your trip, or you can buy it from any of several vendors in any of the US border towns. Your US insurance is not going to be good enough, no matter what it might say on your policy, because it simply won’t be honored in Mexico. If you’re in an accident, you’ll need liability insurance at minimum, and if you don’t have it, there’s a good chance you’ll be locked up, even if you were not at fault. The cost is going to be about $160 for one month. If you’re staying longer than one month, your best bet is a six month policy, which will run about $250. (Figures are totally approximate–there are many variables). One of the better known providers is Sanborns, though there are numerous others. Like anything else, it can pay to shop around.

The border crossings themselves, especially the larger ones, can be chaotic, and the lines move at a snail’s pace. After you exit the U.S., you can expect your vehicle to be inspected by Mexican Customs. That’s generally just a formality, but it’s a good idea to familiarize yourself with all relevant restrictions and prohibitions BEFORE you cross the border, because they have the right to inspect everything you’re carrying in your vehicle. Some things that are legal in the United States, such as firearms or ammunition (even a single loose bullet in the trunk of your car), can land you in prison if you take them into Mexico. Prescription medicines can also be a problem, and as for medical marijuana–what are you, crazy? In any case, be sure to study the regulations carefully.

Once you’re through Customs, you’ll need to find the government offices where they issue tourist cards and vehicle permits. These are generally located very near the border crossing, so be sure to take care of your travel documents before you leave the area. You’ll need to have with you a valid Passport, a valid driver’s license, and both the registration and the title for your vehicle. If your vehicle is financed, you won’t have the title, so you’ll need a notarized letter from your lending institution giving you permission to take the vehicle into Mexico, and specifying the relevant dates. It’s a good idea to make several copies of all of these things, in advance, and to carry them with you. Everything costs, and every step in the process requires waiting in a separate line. First you’ll need a tourist card, valid for up to six months. That will set you back about $26 per person. Then you’ll need a permit to temporarily import your vehicle into Mexico (also valid for six months). That’s going to cost you another $50. Then you’ll need to put down a deposit with Banjercito, a Mexican bank, to insure that you don’t sell the vehicle or leave it in Mexico. The amount of the deposit varies with the age of your vehicle: 2007 and newer, they want $400, which will be returned to you, in full, when you leave Mexico and cancel your permit. Best bet is to put the deposit on a credit card, and at the end of your stay Banjercito will simply reverse the charge back onto that same card. For more detailed information about this process, click HERE. A warning: don’t neglect to cancel your vehicle permit before leaving Mexico. If you do, you’ll not only lose your deposit, you’ll also cause yourself a huge headache if you ever try to go back to Mexico again, with or without your vehicle.

In my own case, I was traveling from Arizona to the Yucatan. The closest border crossing would have been Nogales, but, according to the State Department’s travel warnings, the entire state of Sonora, the city of Nogales and beyond, is considered “extremely dangerous”. That didn’t sound promising. Since the Yucatan is in the easternmost part of Mexico, it made sense to me to travel as far east as possible while still in the US, before heading south into Mexico, in order to minimize the distance that I’d be traveling through the problematic Mexican border region. That meant driving to Texas, somewhere between El Paso and Brownsville. From everything I read, the crossing from Eagle Pass to Piedras Negras was the most highly recommended, but when it came down to it, I actually crossed at Laredo, because it was a more direct route from my starting point on the day when I headed south. The crossing at Laredo was a slog–long, slow lines of traffic, followed by long, slow lines of people at the various service windows as we worked our way through the insanely inefficient document process. From start to finish, it took close to three hours to negotiate the border and all its formalities, so it was getting late by the time we got on the road, and it was well past dark before we got to Monterrey, where we stayed our first night. If I had it all to do over again? I would have gone the extra distance to Piedras Negras (we returned by that route when we left Mexico, and the crossing really was much less congested). I also would have gotten an earlier start, to allow for the inevitable delays.

Heading South

A universal recommendation, strongly, emphasized in every Mexico travel guide I’ve seen: whenever possible, you should stick to the toll roads (the” Cuotas“), as opposed to the free (“libre“) alternative routes.

Take the left fork, the (toll) road less traveled…

The cuotas aren’t cheap–depending on the route you take, it can cost you as much as $200 US–in tolls alone–to travel from the northern border of Mexico to the southern border:

Pay up! Tolls are payable in Mexican Pesos, and you’re advised to keep a stack of small bills and coins handy.

Click either of the thumbnails (above) to be linked to a point-to-point route planning site sponsored by the Mexican government, complete with toll costs, Highway numbers, and mileage

It’s well worth the cost, because the toll highways are newer, faster, and far better maintained; they generally carry less traffic, and you’re far less likely to run into the sorts of trouble that the advisories warn you against. The free roads are more interesting, as well as more scenic, but they’re infinitely slower, because they run smack through the center of every tiny town along the route. On the free roads, you’ll be dodging livestock, street vendors, and deep, dangerous potholes big enough to blow your tires if you hit them at speed. You have to remain hyper-alert, not only for hazards in the road ahead, but also for other drivers, because you’ve got cars, trucks, and buses swerving back and forth all over the place, avoiding the many hazards on their own side of the road. And then there are the beloved “topes”, the Latin American version of speed bumps, put in place to slow traffic through populated areas. Some of them are well marked, painted bright yellow or white, with signs posted in advance, warning drivers to slow down:

Some topes are marked with signs

Some topes are marked with signs

Some are marked with both signs and reflective paint

Others aren’t marked at all! They’re camouflaged, the same color as the asphalt, and if you hit one of those suckers going faster than, oh, say, 5 mph? Well, let’s just say you’ll wish you hadn’t. A good trick is to follow another vehicle, staying a few car lengths behind, and watch for their bobbling brake-lights, or the telltale swerve to the left or right as they try to steer around the ends of a tope, or to hit it at an angle to soften the blow.

Another fact of life in modern Mexico is the police presence, both Federal Police (Federales) and the Mexican Military.

There are truckloads of soldiers on the highways:

There are roving pickup trucks with 50 Caliber machine guns mounted in their beds, and of course there are the Retenes, the checkpoints, some permanently in place, others that are moved around to catch drivers by surprise. It can be fairly intimidating for someone who hasn’t seen that sort of thing before: you roll up on a squad of soldiers in SWAT gear, all carrying automatic weapons, and they surround your car, asking questions in rapid-fire Spanish and demanding your documents. You look off to the right, and a carload of young Mexican guys are all face down on the road, hands clasped behind their heads, while soldiers are tearing their vehicle apart. It might sound a bit counter-intuitive, but you shouldn’t be afraid of these guys. You might not agree with their heavy-handed methods, but the whole reason they’re out there is to keep the roadways safe for us fat, privileged tourists, and that’s very much to our advantage. So–unless you’re an idiot who is running guns or smuggling drugs, you should be happy to see them. Be polite, answer their questions as best you can, and I can all but guarantee that you’ll be waved on your way, with a smile and a wish for a “buen viaje” (a good journey). In four weeks, I passed through at least 60 of those checkpoints, and never had a single negative experience.

There is one thing I should note: license plates. Arizona is one of many U.S. states that no longer issues a front license plate. In Mexico, all vehicles have front license plates. So when you pull into a checkpoint, they see you approaching, and they don’t see a plate on your car. That’s a natural reason for them to stop you, which they will do, almost every time, and you’ll need to explain, in Spanish, why there isn’t a license plate on the front of your car. That wasn’t a problem for me, because my Spanish is fairly good, but if you don’t speak the language, this can turn into an ongoing aggravation. I’m told that it’s possible to take your rear license plate to a sign shop in the U.S., and to have a copy made on plastic or metal that can be mounted on the front of your car. It won’t be a real, legal plate, but it doesn’t have to be. It’s a match for the real plate on the back, and it will head off potential confusion at the checkpoints.

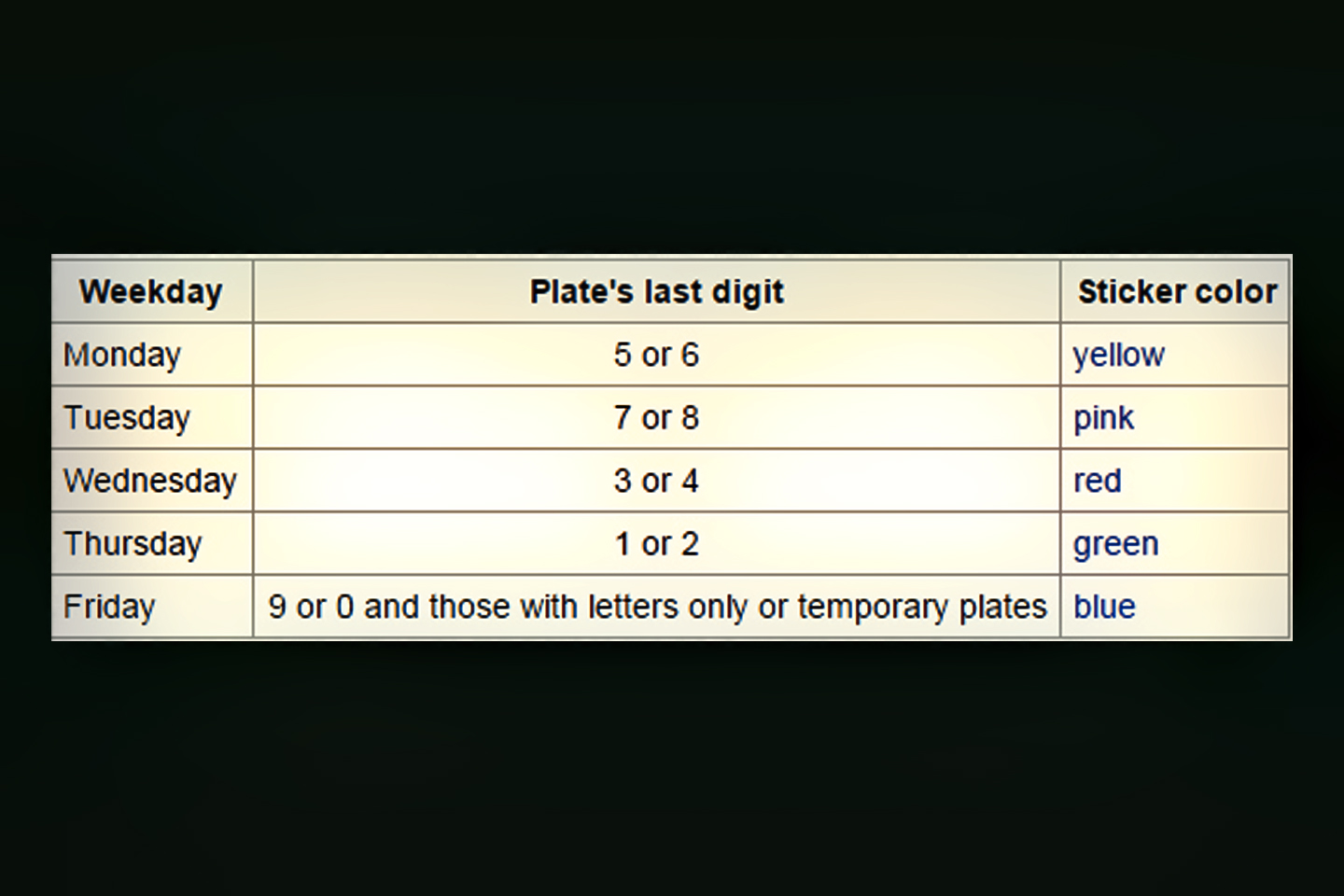

Another note about license plates: if you’re traveling in the D.F., (Distrito Federal), which consists of Mexico City and the surrounding area, there is a law, called Hoy No Circula (roughly, Don’t Drive Today), which requires all drivers to leave their car at home one day per week. Mexico City, the second largest metropolitan area in the entire world, has enormous problems with air quality, so the programs they’ve put in place to mitigate auto emissions are among the most stringent anywhere. The last number or letter on your license plate determines which week day is your No Drive day. If it’s a 5 or a 6, for example, your car can’t be used on a Monday, or you risk a hefty fine. As a tourist, you’re allowed a 14 day exemption to this program (called a Pase Turistico), but you have to apply in advance, and carry the paperwork in your vehicle. Otherwise, the law is the law, and ignorance of the law is no excuse. Note that this only applies to Mexico City and the surrounding State of Mexico, so one obvious way to avoid all that aggravation is to just not go there. That’s how I handled it on my way south–I took the route through Puebla and skirted the D.F. altogether, passing by it on the eastern flank without actually entering it. Coming back, I planned to do the same thing, but missed a turn, and ended up crossing the border into the State of Mexico. On the toll roads, it can be difficult to recover from a missed turn. It’s a long way between exits, and they don’t always provide a Retorno, a place to turn around, especially in areas where there’s construction. In this case, by the time I was finally able to pull over and check my map, I’d already passed the point of no return. By far the easiest course was to keep going on the wrong road until it merged back into the right road, near the city of Queretaro. That’s how I found out about “Hoy no Circula“. Shortly before crossing back out of the State of Mexico, I slowed to enter the line of vehicles at a toll plaza. A marked patrol car appeared out of nowhere, whipped up directly behind me, hit his lights, and pulled me over. A pair of well-fed Mexico State Policemen got out, and approached us on the driver’s side. They told me about the law, told me that I’d broken it, and informed me that I’d not only have to pay a fine, I’d also have to park my vehicle until the following day. I protested, naturally, so the two guys looked at each other, then they both looked back at me and smiled. If I could pay the fine right there on the spot, in cash, they informed me, they’d give me a receipt, and I would be allowed to continue on my way to Queretaro without further incident. How much? 5,000 Pesos–which is almost $300! That seemed pretty steep, but because I did not know the law, because I wasn’t sure of my rights, and because I most definitely didn’t want to park my car somewhere until the following day, I went ahead and paid the 5,000 Pesos. They gave me the receipt, and I drove off, feeling like I’d just been robbed. As it turned out, I HAD just been robbed! When I researched the regulation–after the fact–I discovered that the whole incident was bogus from the beginning.

The day they stopped me was a Friday. As you can see from this chart, the No Drive day for my vehicle, with a plate number ending in 4, was Wednesday. This was black and white, not something that was subject to interpretation, so in point of fact, I hadn’t violated any laws, and even if I had, the fine would not have been anywhere close to 5,000 Pesos. The so-called receipt they gave me was the real tip off: scribbled on a scrap of paper, it was signed “Officer Plata”. Big joke, and the joke was on me! Plata is the Spanish word for silver, and it’s a common slang term for money paid as a bribe. Ha!

The day they stopped me was a Friday. As you can see from this chart, the No Drive day for my vehicle, with a plate number ending in 4, was Wednesday. This was black and white, not something that was subject to interpretation, so in point of fact, I hadn’t violated any laws, and even if I had, the fine would not have been anywhere close to 5,000 Pesos. The so-called receipt they gave me was the real tip off: scribbled on a scrap of paper, it was signed “Officer Plata”. Big joke, and the joke was on me! Plata is the Spanish word for silver, and it’s a common slang term for money paid as a bribe. Ha!

From what I’m told, Mexico is a lot better than it used to be. From the top down, the current government is assiduously weeding out corruption, and prosecuting any officials, including policemen, who get caught with their hand in the till. Unfortunately, the whole concept of “La mordida“, “the bite”, is so ingrained in the culture that there will probably always be incidents like the one I just described. I equate la mordida to the cost of doing business, and in this case, at least, it was also a lesson learned: always do your homework, and be aware of the rules, which can vary, from one place to another. If you do plan to drive in Mexico City? Be aware of Hoy No Circula. If you’ll be there more than a few days, get yourself a Pase Turistico, the 14 day exemption. And you should definitely know which day of the week is the No Drive day for your vehicle, lest you get snookered the way I did.

If, in the course of your travels, you ever do get pulled over by Mexican law enforcement, it’s just like anywhere else: you should never argue with them, and you should always be polite. Let them explain your supposed violation, and if you have good reason to suspect that it’s bogus, there are a few things you can do. For starters, play dumb. Even if you speak perfect Spanish, play along as if you don’t speak a word. Ask to see the officer’s badge and identification. Ask to see the law that you’ve broken, in writing. If they want money, agree to pay, but tell them you’ll only pay at the police station. Speak only in English, and tell them, repeatedly, that you don’t understand a word of what they’re saying back to you. This technique won’t always work, certainly not in the case of a real infraction, but I’m told that it’s effective at least some of the time, especially when you’re approached by an out and out scammer (like my Officer Plata). If you make it hard enough for them? Sometimes they’ll give up, and let you go out of pure frustration.

Something else you may run into on the road in Mexico:

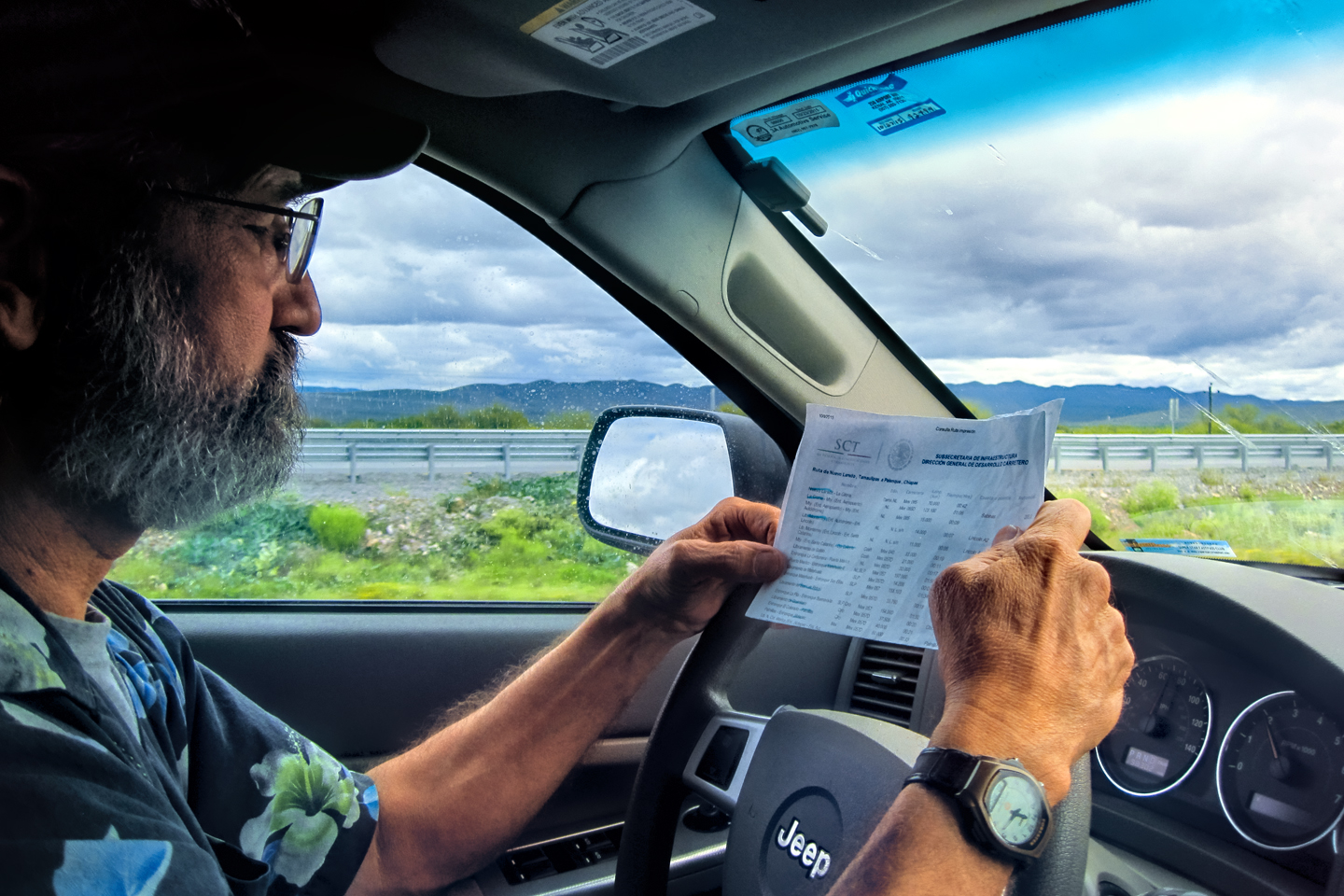

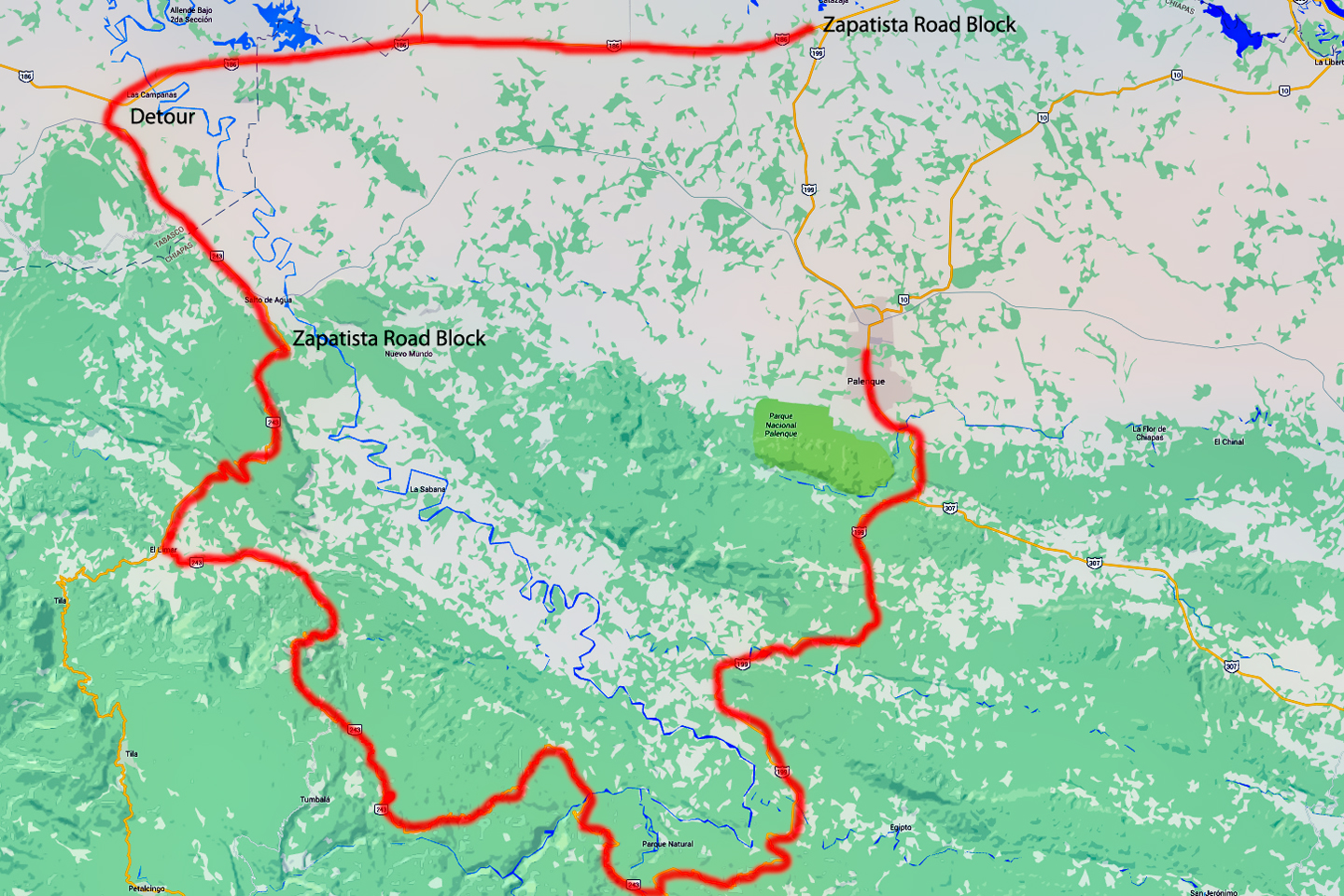

When we drove to Palenque, the first of the Mayan ruins that we planned to visit, we ran into a traffic jam, right at the intersection of the road from Villahermosa, where we’d stopped the previous night. There was a toll plaza just before the crossroads, and a group of mostly Indigenous political activists known as the Zapatistas had shut it down, blockading the highway in both directions by parking trucks across the road, right at that choke-point. Hundreds of protesters carrying signs were in a standoff with the Federales, and from what we were told, nobody would be moving on that road until the following day (at the soonest)! The Zapatistas, who have been around for the last 20 years or so, put up these roadblocks on a sporadic basis to bring attention to a litany of social and environmental ills. They want to put a stop to oil drilling, dam building, and new highway construction in the state of Chiapas. They want to put an end to illegal logging, drug trafficking, and arms trafficking. They want a living wage for peasant workers, an end to government corruption. These are all worthy goals, at least, from their perspective, but their methods are quite disruptive, and harmful to the local economy. I spoke to a number of local people about these issues, and the Zapatistas most definitely do NOT have universal support. The savvy truck drivers at the roadblock had seen all this before, and they were taking it in stride. Many of them were simply sleeping in the shade under their vehicles, settling in for a long wait. All we wanted to do was proceed to Palenque, less than 20 miles away, but at that point, it wasn’t looking good. I studied our road atlas, an excellent spiral bound map book called the Guia Roji (highly recommended).

The route outlined in red on this Map is the detour that I had to take to avoid a Zapatista road block. Not such a smart plan: I ran right into a smaller Zapatista road block, designed to catch anybody (like me) trying to sneak in the back way. What an adventure that turned out to be! Click for an expanded view.

I noted that there was an alternate route to Palenque. If we backtracked about 40 km toward Villahermosa, there was a dirt road, Chiapas State Route 243, which took a long way around and hooked into MX Route 199 south of the town of Palenque. It was pretty far out of the way, but it looked worth a shot. Anything would be better than spending the day trapped in a traffic jam (especially a traffic jam which had the potential of blowing up into an armed confrontation). I whipped around in a U-turn, and headed back the way we’d come. The road we were looking for was hard to spot. It was very narrow, like a country lane, and in terrible condition, but there was a sign for a town called Salto de Agua (Waterfall), 8 km further along, and that was exactly the way we needed to go, according to our map. We bounced and jolted our way along over deep ruts and crumbling pavement alternating with mud, finally reaching the village of Salto de Agua after half an hour or so of very slow going. There was a fork in the road at center of the town. My friend, who was navigating, told me to go left. My gut told me to go right. I’d seen a policeman, on foot, just behind us, so I turned around, and stopped to ask him:

“Which way to Palenque?”

“Back to the main road,” he informed us. “That’s the way to Palenque.”

“But the highway is closed,” I replied. “No traffic is moving past the crossroads.”

“Ah,” said the policeman. “The protest. But even so, that’s the only way to Palenque. You’ll have to head back the way you came.”

“My map says that this road goes on to Palenque,” I opened up the atlas, and showed it to him.

He studied the lines on the map, tracing them with his finger. “Yes,” he admitted with a shrug. “It is possible, but you really don’t want to go that way. It’s a terrible road!” He said something else after that, but I didn’t quite catch it, and besides, he had me at “terrible road”. I drive a Jeep, after all, and I love that sort of challenge!

We took off, then (the fork to the right), and after a few kilometers we ran into another fork. This time, the fork to the right was blocked. Six young men with machetes had stretched a chain across the road, and they were staring at us defiantly. This was apparently an extension of the blockade on the main highway, but after driving all that way, I didn’t want to give up so easily. I rolled slowly up to the roadblock, and put down my window.

“Good afternoon,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you let us pass?”

“The road is closed,” said the leader of the group, a young Mayan lad who fixed me with a menacing glare, his hand on the hilt of his machete.

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing the machete, while his companions did the same.

I didn’t like the sound of that. Not at all, so I gave him a blank look and said, “No entiendo.” (I don’t understand).

“No entiende?” he repeated back to me, a bit perplexed. He wasn’t quite sure how to deal with that.

“How about you take ten Pesos,” I said, pressing a large, gold-colored coin into his hand. He stared at the coin, worth about 60 cents. It was such a ridiculous offer, he wasn’t sure if he should laugh, or attack me. The other guys dropped the chain, and we sped away across it, before they changed their minds. There followed about three hours of incredibly slow going over what really was a terrible road, but it was beautiful, and driving it was great fun. When we got to the other end, just before we rejoined the paved highway south of Palenque, we ran into another roadblock, set up a little differently. At this one, they had a long board with nails driven through it from the bottom side, like a homemade stop stick. We slowed down as we approached, and watched as they pulled their board back to allow a small local shuttle van to pass, those little vans being the only traffic that was “officially” allowed through the blockade. While the van scooted past the stop point headed west, we shot around them headed east, and just barely made it past, as they attempted, unsuccessfully, to jam their board full of nails under my tires, loudly yelling at me to stop.

A sign on Mexico Route 199 between Palenque and the town of San Cristobal de Las Casas, advising travelers that they have entered the territory of the Zapatistas. I would never advise anyone to do what I did when confronted by a Zapatista road block, or any other political action that you might run across while traveling in Mexico. The best advice, in fact, is to steer clear. Don’t engage, don’t get involved, go back the way you came and lie low until things settle down again.

An hour or so after evading that last roadblock, we were safely checked into a nice hotel in the town of Palenque, and we headed for the ruins, which were all but devoid of visitors. The blockade had kept the other tourists away, so we had quite a wonderful time of it, with the ruins of that extraordinary Mayan city almost all to ourselves.

Click the thumbnail (above) to read my post on Palenque

Let’s see–before I wind this up, do I have any other advice or words of wisdom for folks who might want to tour Mexico by car? Keep your eyes open, expect the unexpected, and enjoy! Mexico is a wonderful country, with wonderful people, and I had some of the best fun of my entire life on my trip to the Yucatan. I drove 8,000 miles over the course of a month. I made a complete circuit of the Yucatan Peninsula, touched the border of both Belize and Guatemala, as well as both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the country. I visited a total 14 Mayan sites, and attended wonderful fiestas in five different colonial cities. That’s a lot of wonderful stuff, packed ito a single month. A lot of great memories, and a ton of great photographs, many of them ranking among my personal all-time favorites. Check out my other posts in this category if you’re interested in the details. Every post concludes with a slide show, and some of those pictures are stunners.

Note: most of the photos associated with this particular post are courtesy of Michael Fritz. Some are a bit out of focus, but then again, so was Michael.

Here’s to you, Mr. Whiskers!

The slide show below features additional photos taken on the road in Mexico by my inestimable shotgun rider, Michael Fritz. Click any image to expand them to full screen:

(Unless otherwise noted, all of these images are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.)

READ MORE LIKE THIS:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

MEXICAN ROAD TRIP: HOW TO PLAN AND PREPARE FOR A DRIVE TO THE YUCATAN

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

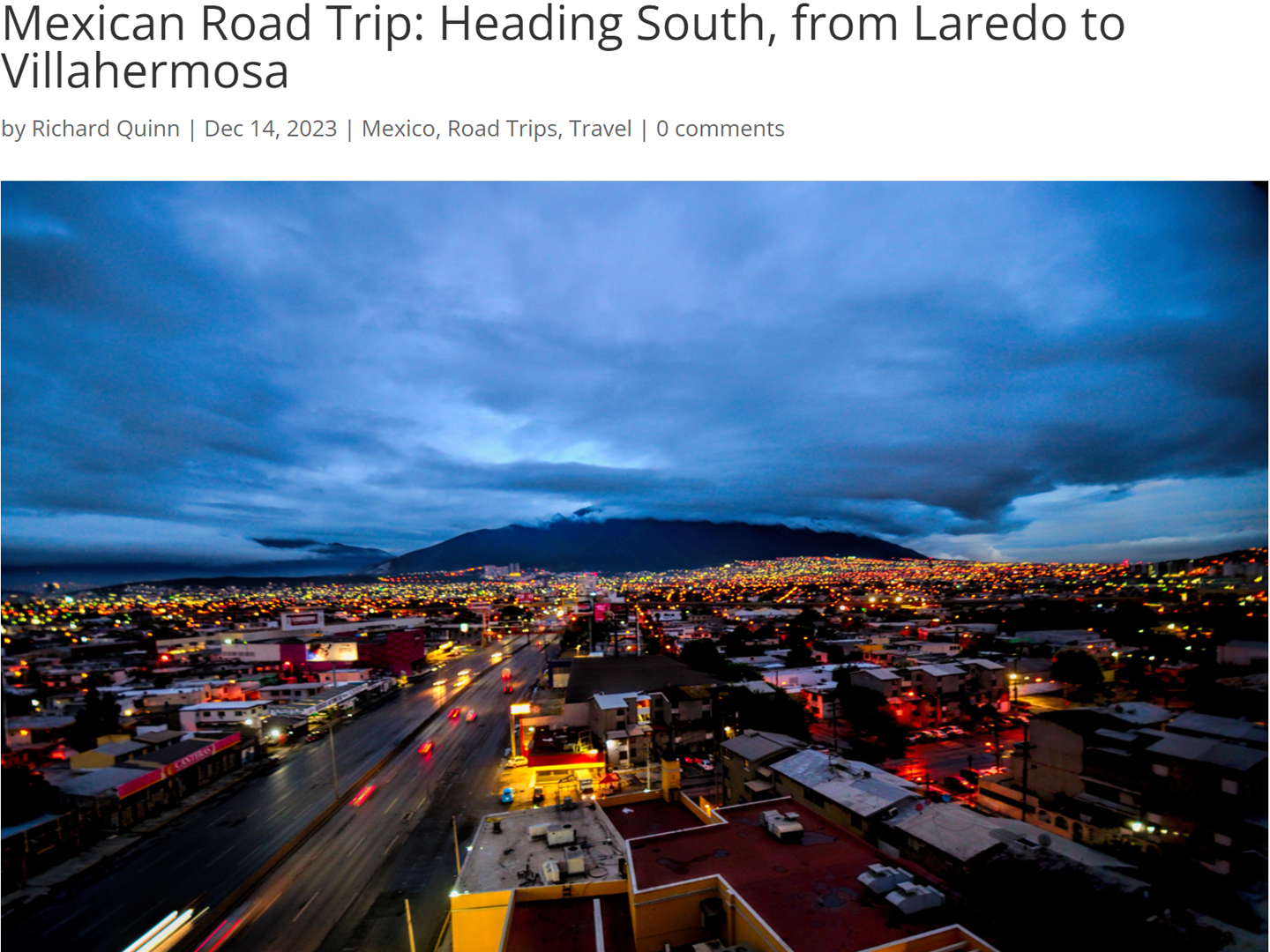

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

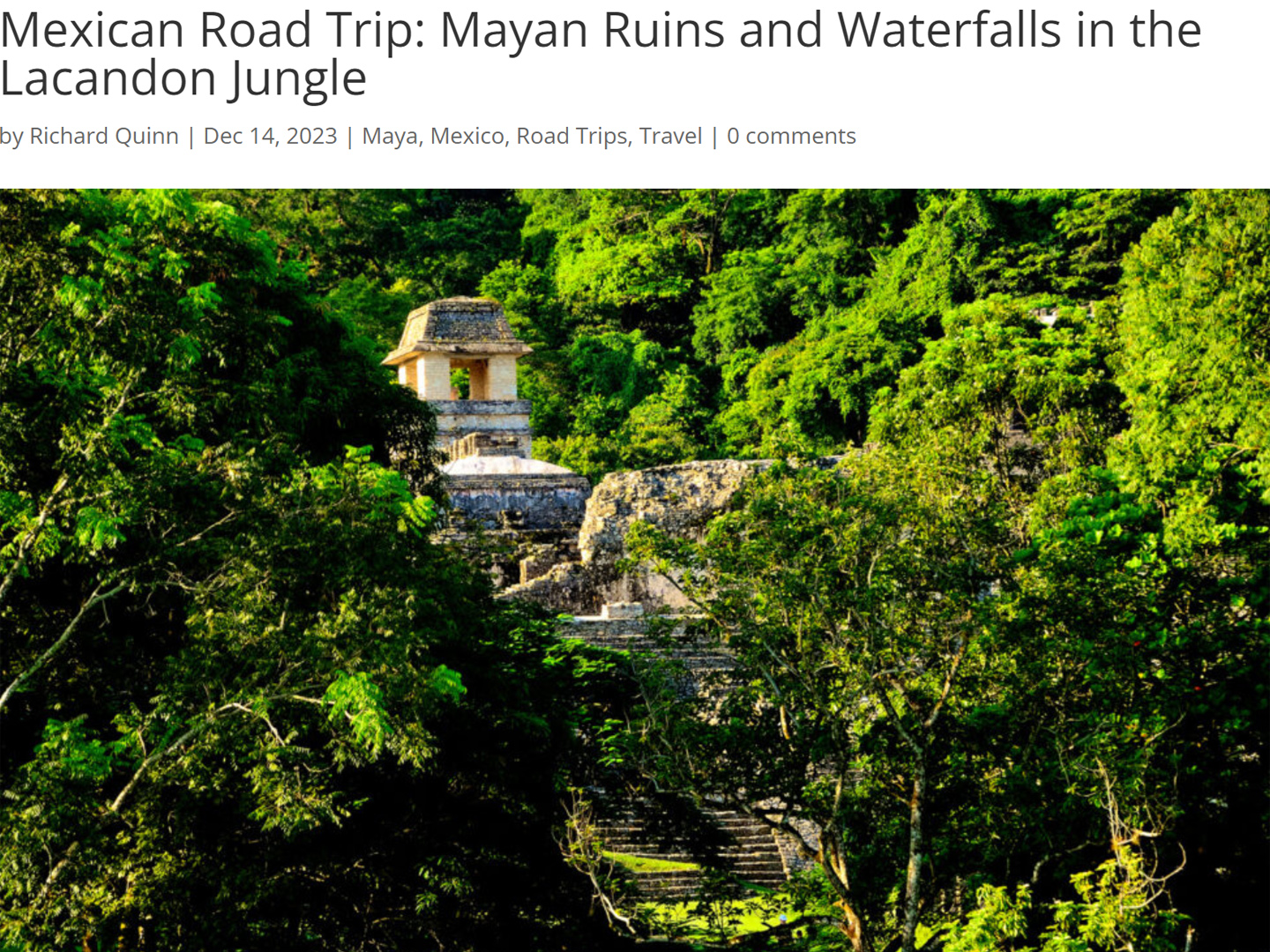

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancun, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancun from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

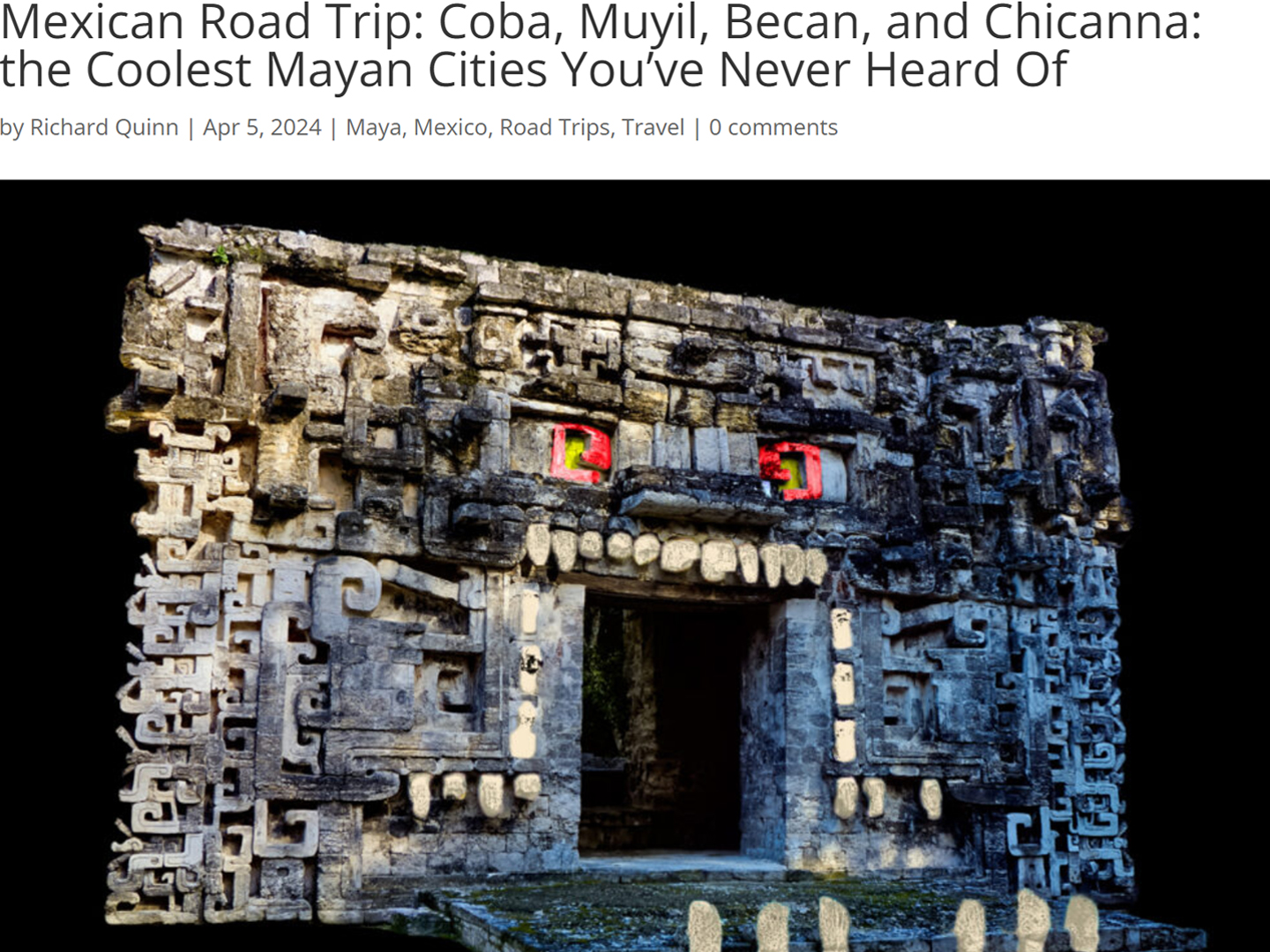

Mexican Road Trip: Cobá, Muyil, Becán, and Chicanná: the Coolest Mayan Cities You've Never Heard Of

After Tulum, we drove south, then west, headed back to Campeche. Along the way, we visited some Mayan ruins that are less well known, starting with Cobá. the major Mayan city northwest of Tulum, followed by Muyil, Becan, and Chicanná. Each site was unique, and each of them added another piece to the puzzle of the ancient Maya.

(This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication: April, 2024)

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

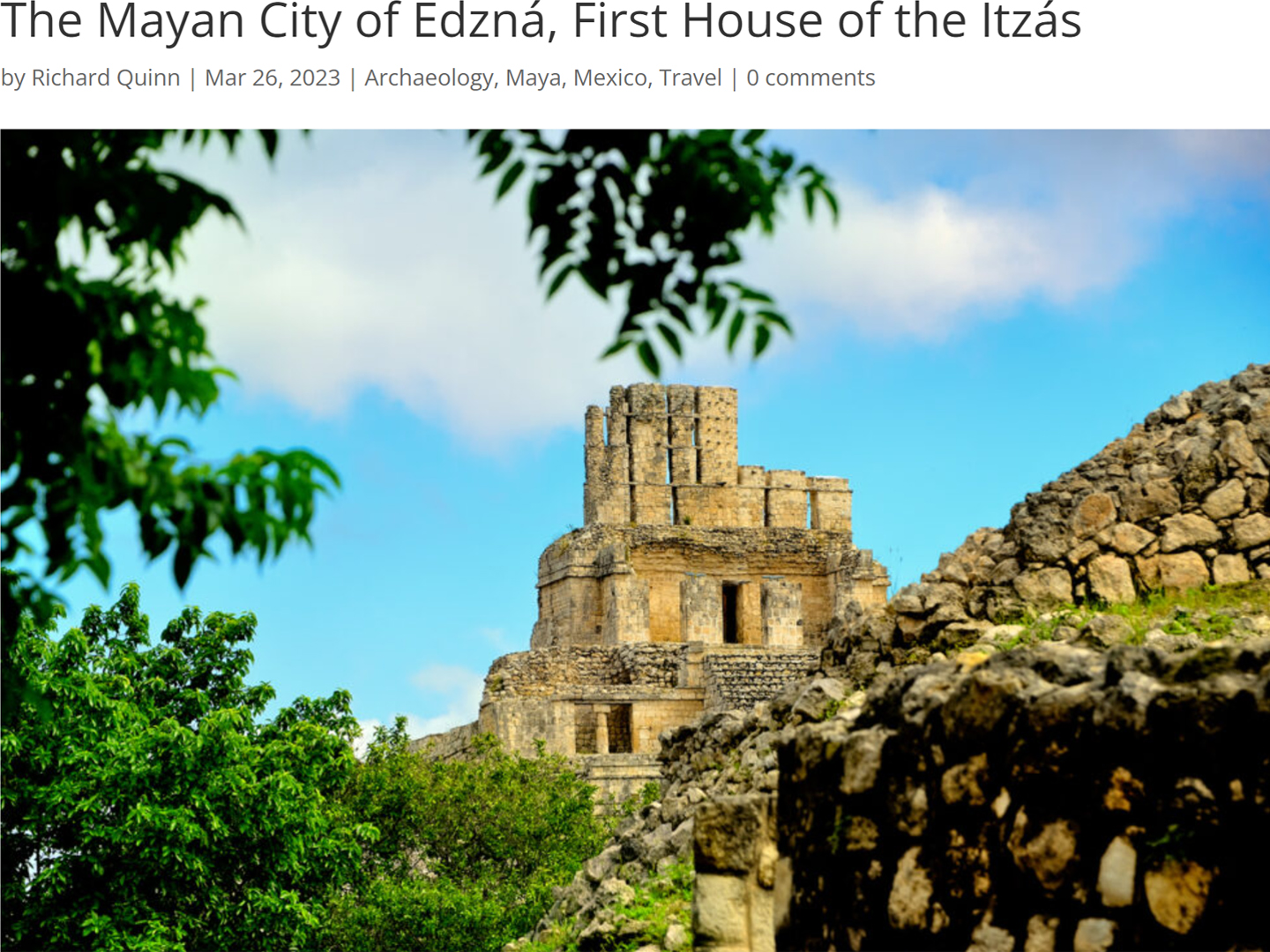

Mexican Road Trip: Campeche, Edzna, and La Guaranducha

(This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication: May, 2024)

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

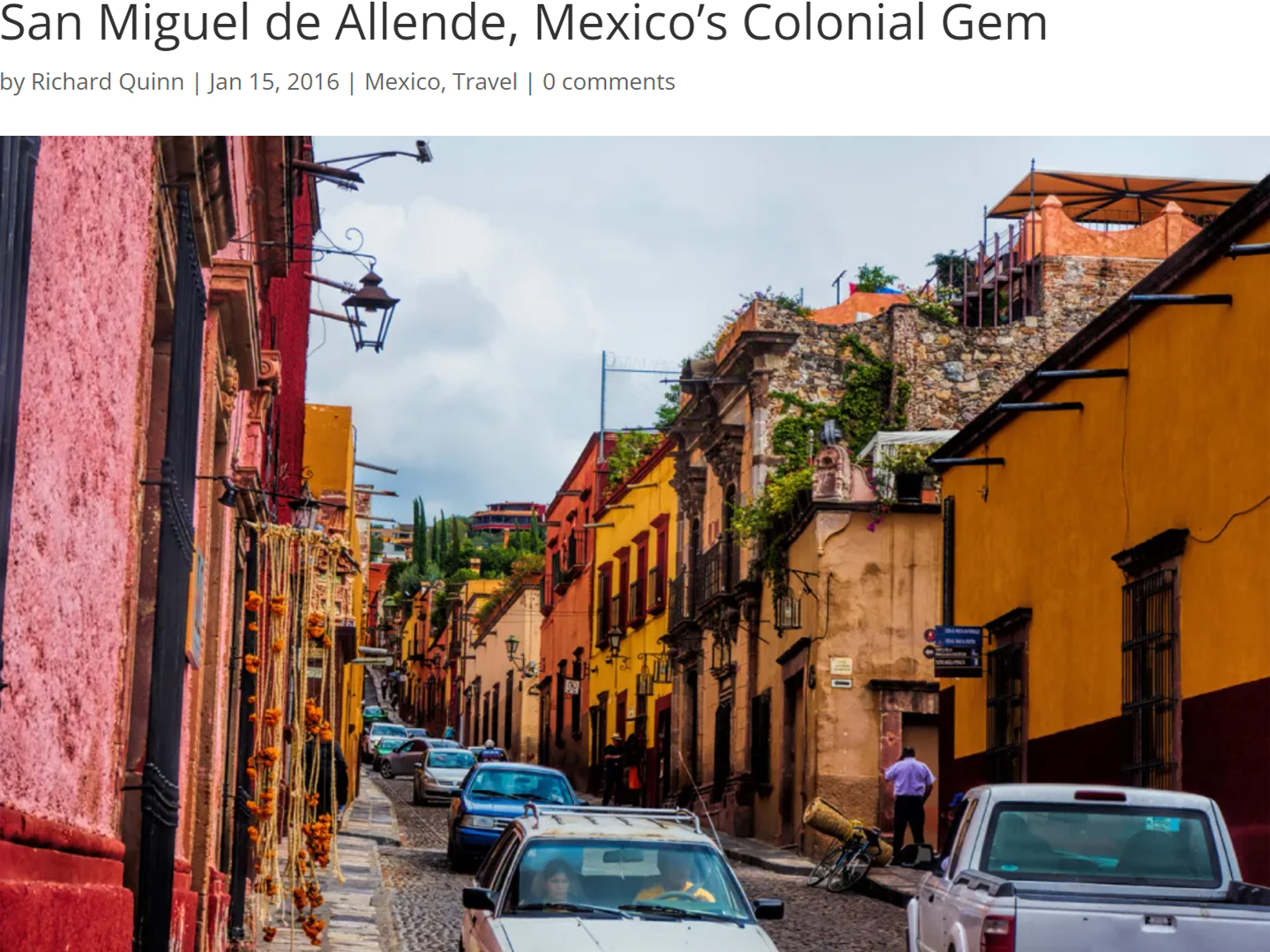

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico's Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they've adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It's a wonderful, colorful parade that's all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

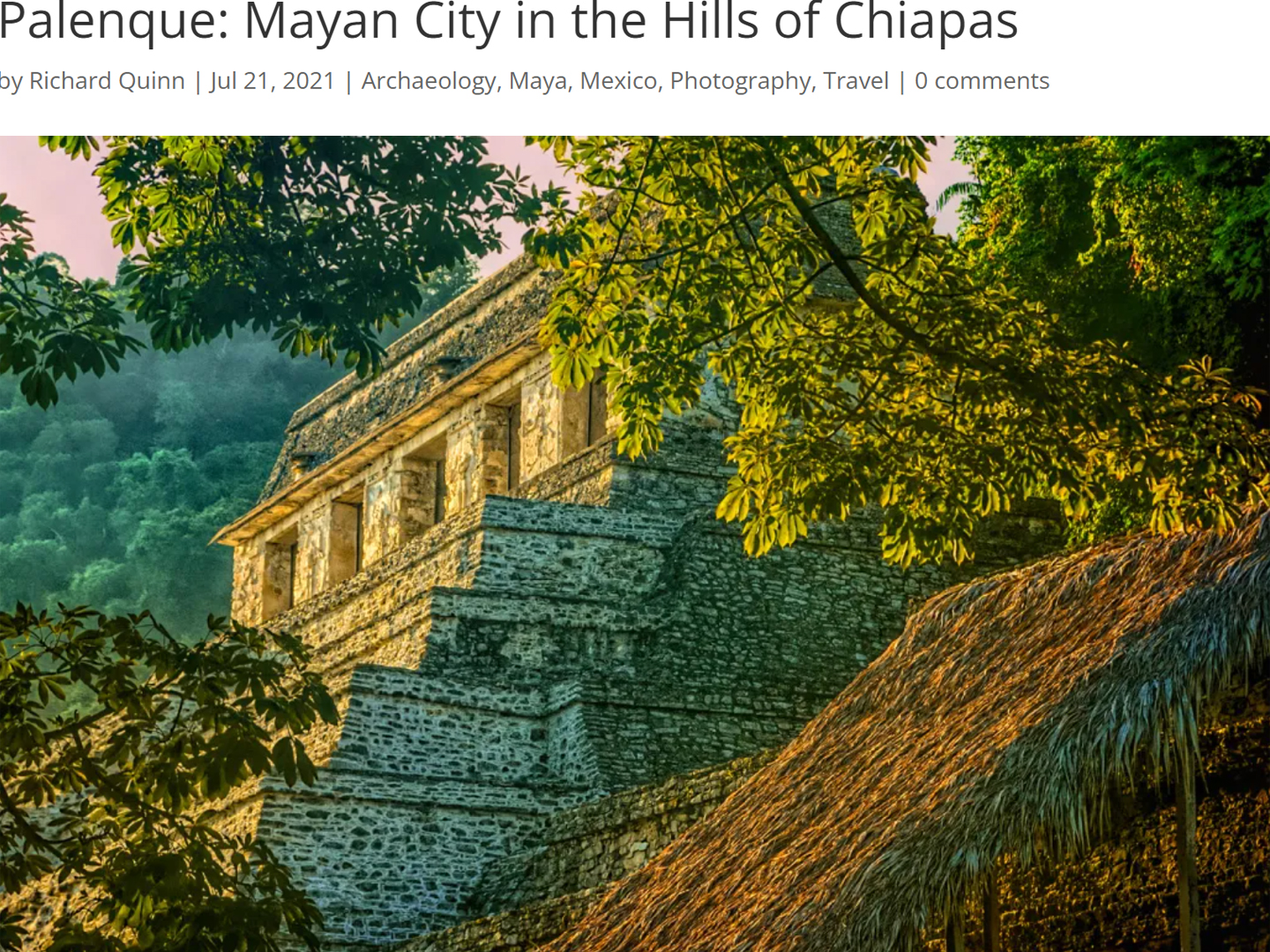

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

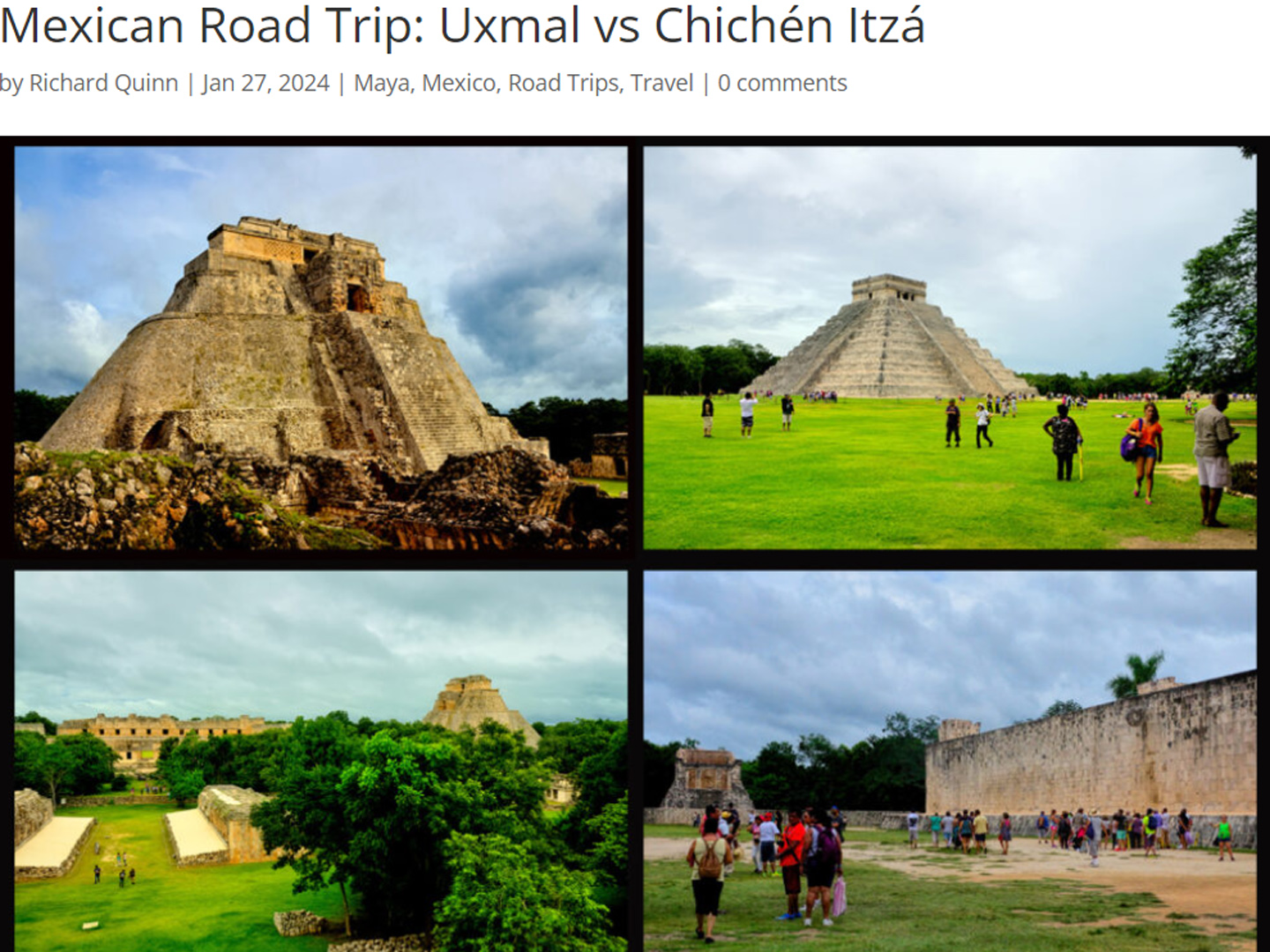

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I've ever seen. There's a powerful energy in that spot--maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps--but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I've ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I've ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

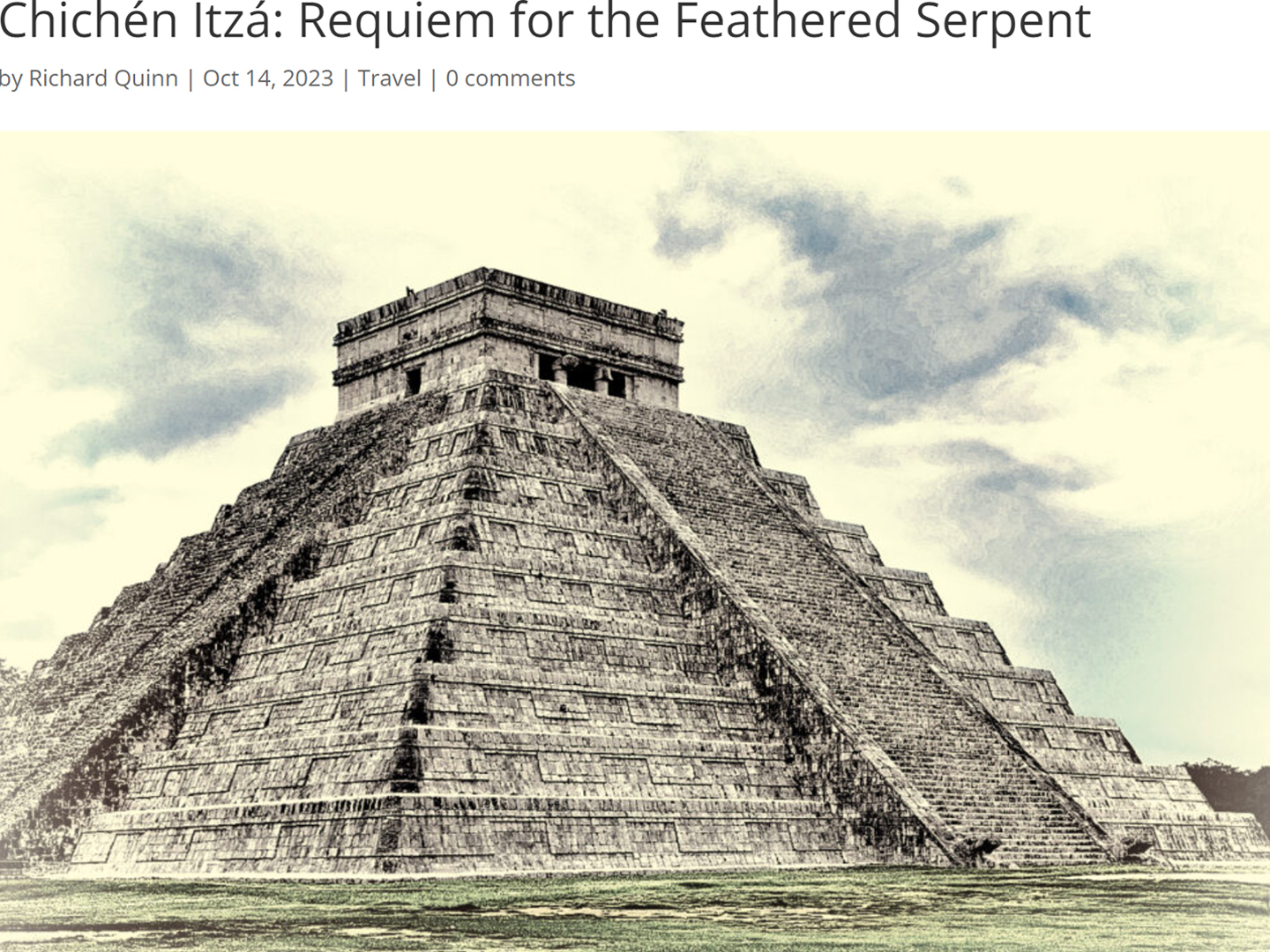

Photographer's Assignment: Chichén Itzá

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

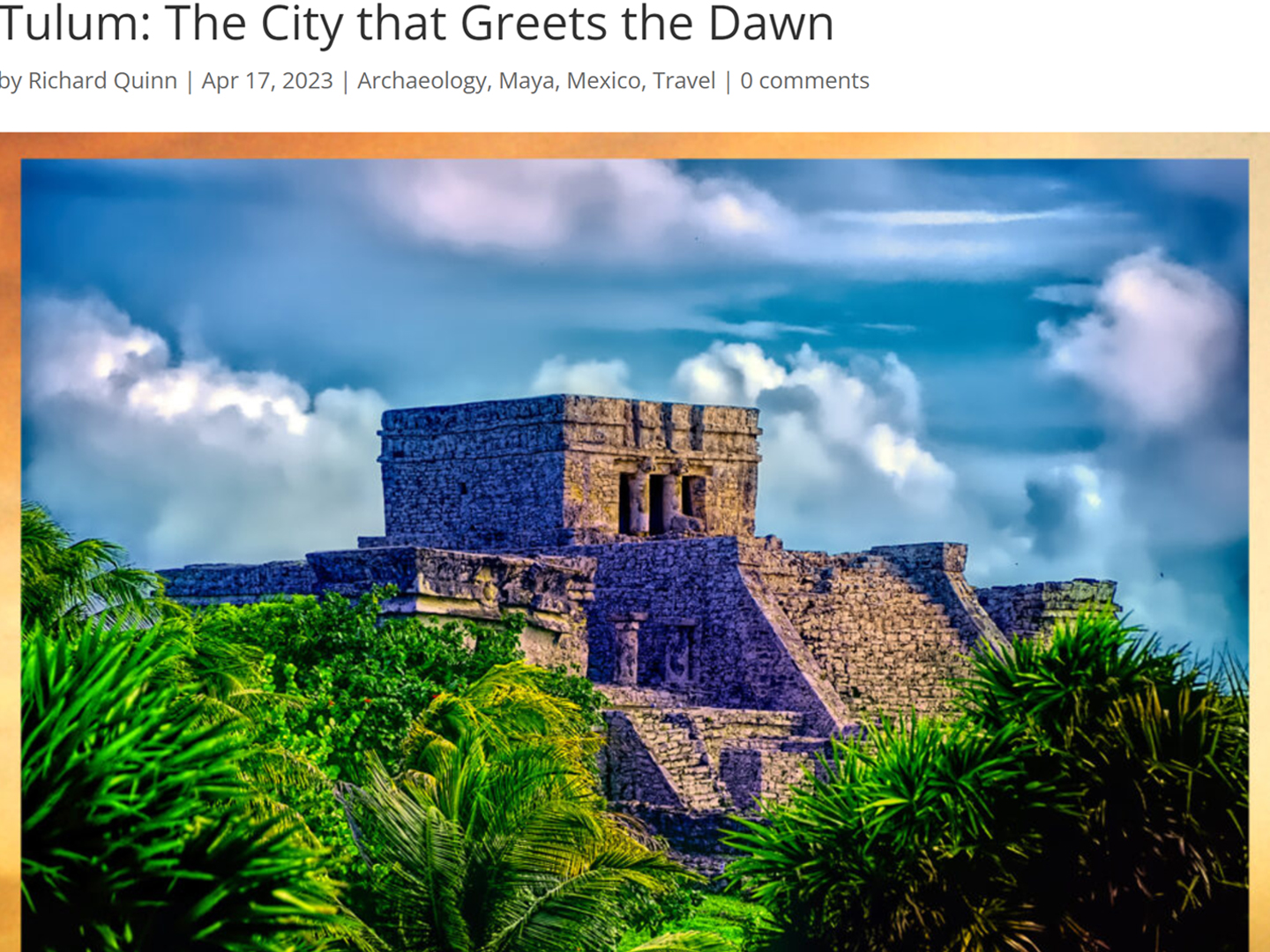

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

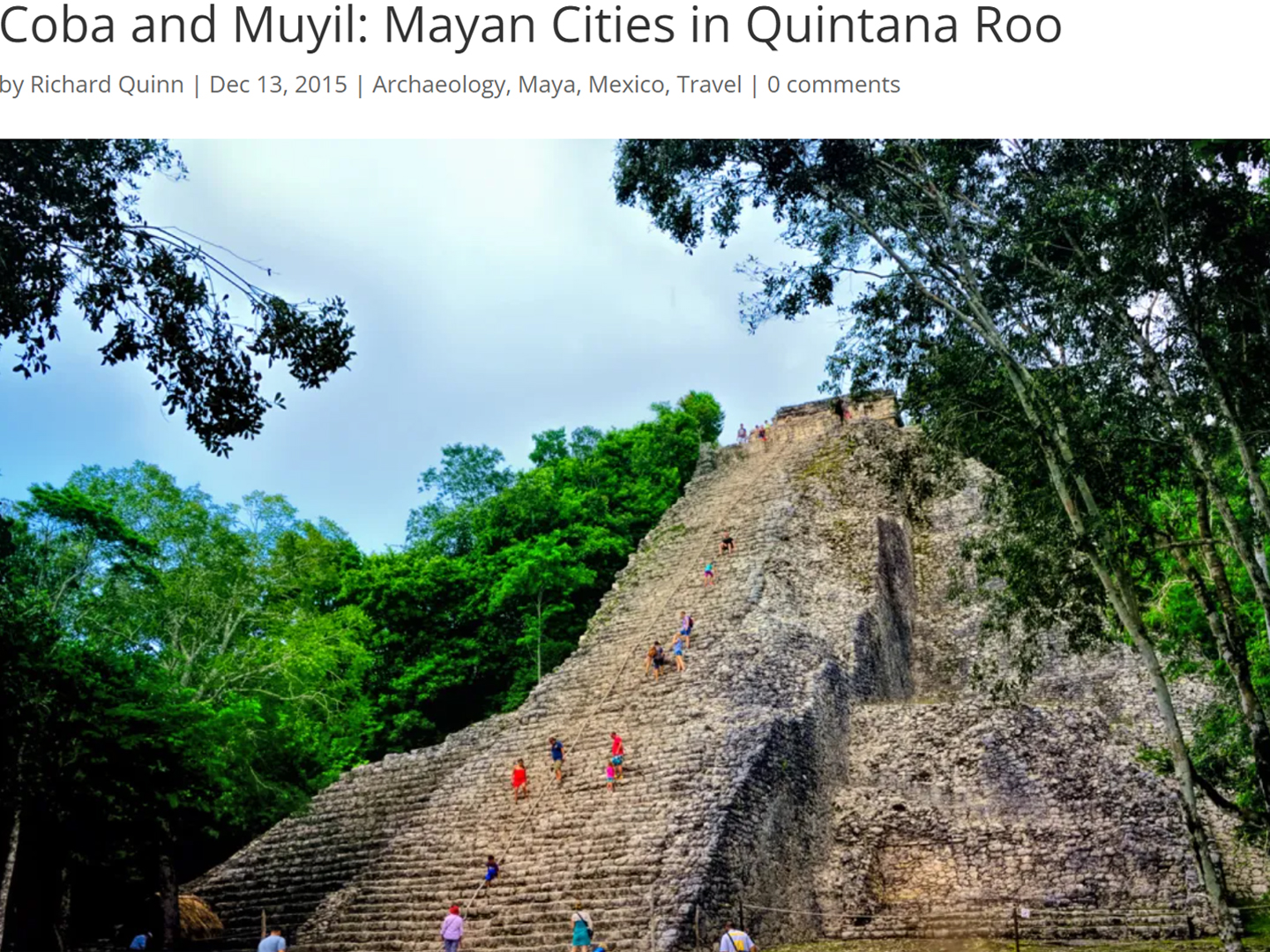

Cobá and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Cobá was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

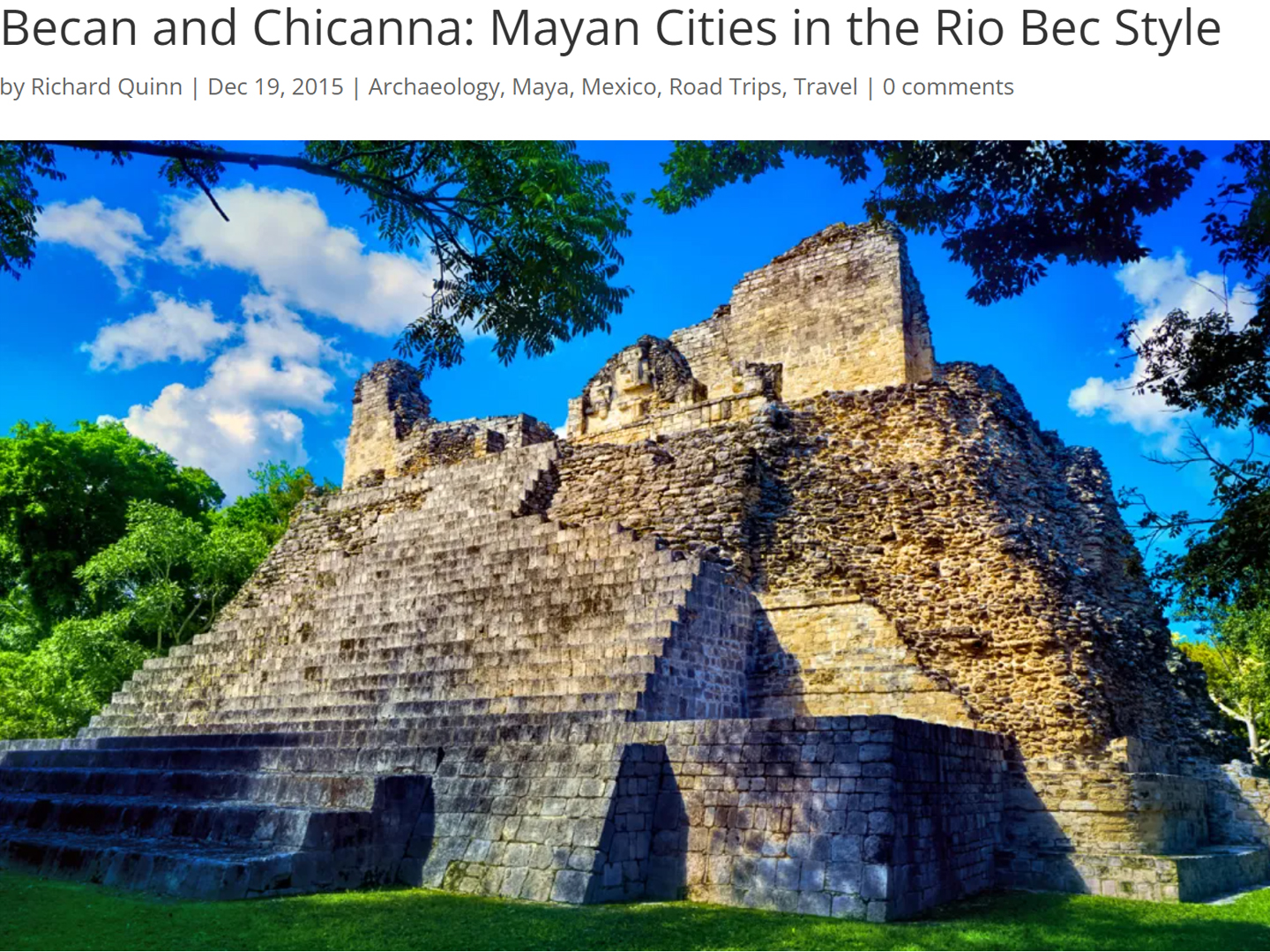

Becan and Chicanná: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

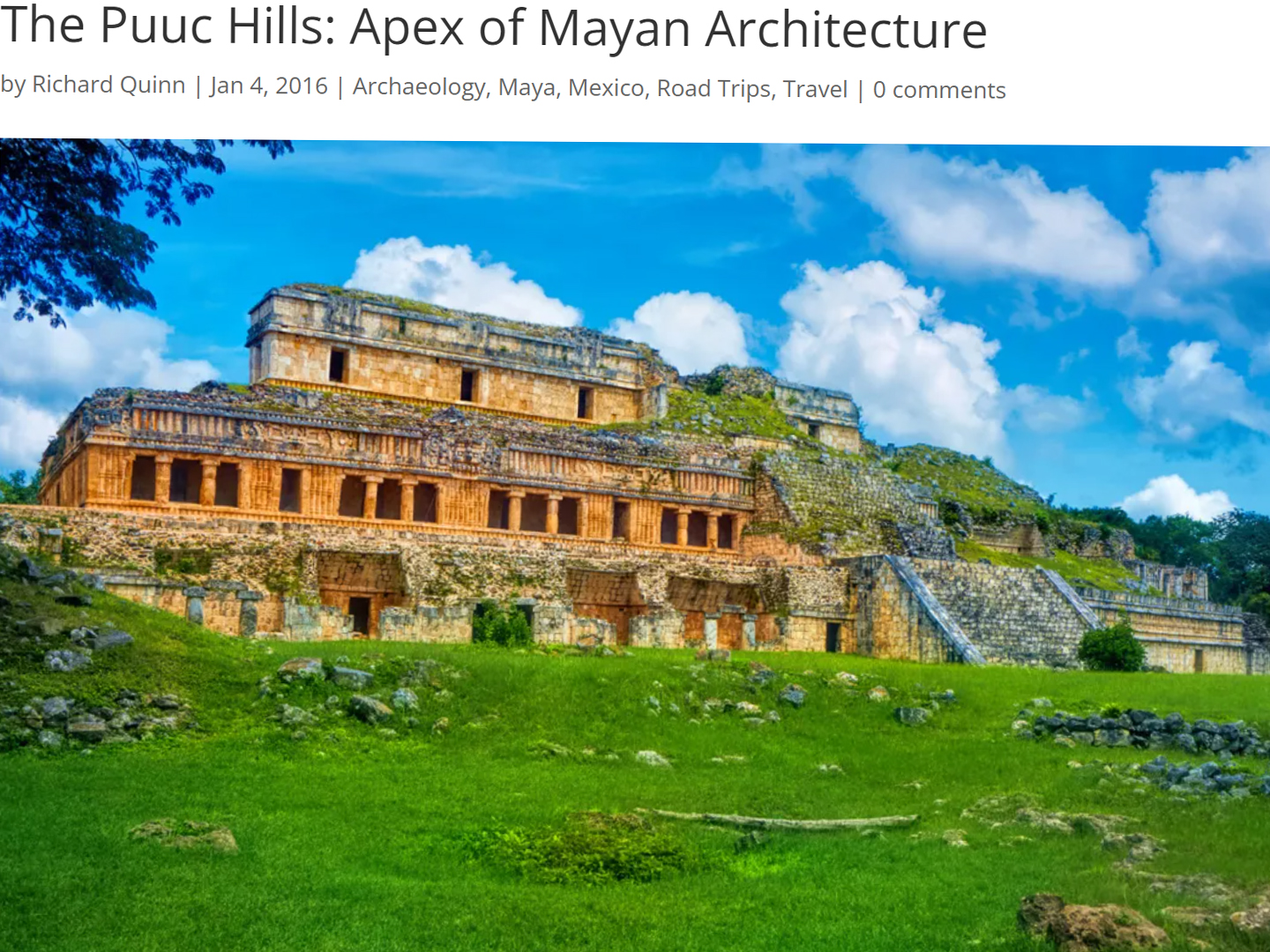

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

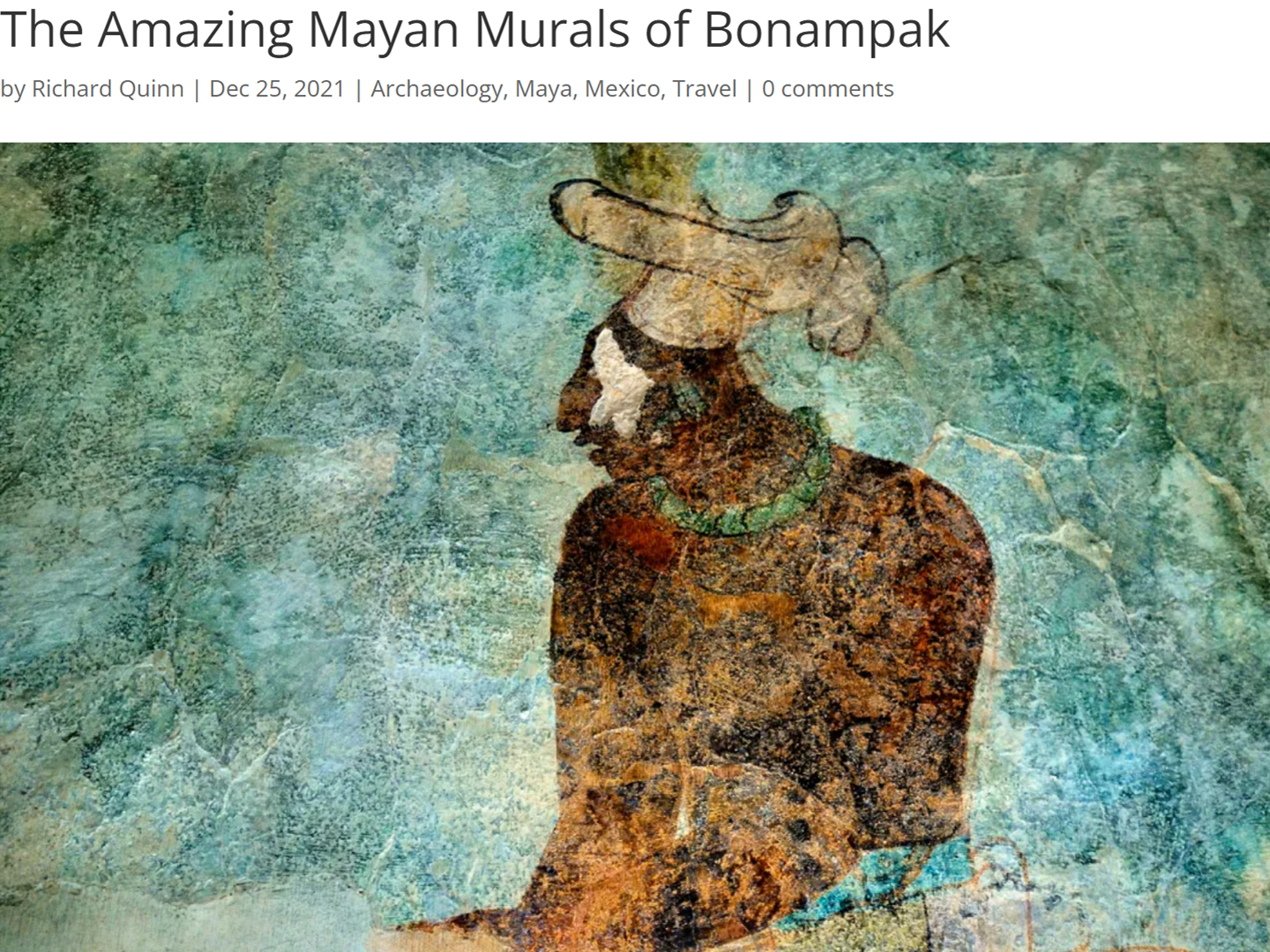

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

A shout out to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. "Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins" was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after "Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali." We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Road trips with old friends are the absolute best. We laugh and we laugh until we run out of breath, and laughter is good for the soul!

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Hyo Ricky

Mostest bestest road trip ever Dude. Claro que Si.

Cant wait to see the rest of the blogs.

Tre kool amigo. Tre kool

–Miguelito (AKA-“Mr Whiskers”)

Hi there, we are traveling to Merida by car on Oct 7th 2022. Love all the info by the way. Do you have advice on what route to take and where to spend the night? We are in AZ but plan to go to Tx to cross. We are taking our 90 lb dog with us. Will that be a problem in hotels? We want to take only toll roads and travel during the day. Are there caravans that go that way? How is the weather? Thank you for any help.

Hello!

My sincere apologies for the delayed response. Note that the following are simply my recommendations, based on my own experience; you may set a faster, or slower pace, in which case your stops might vary.

Heading to Texas before crossing the border is exactly what I would recommend. Eagle Pass is a good crossing point; it’s less hectic than El Paso or Laredo. Take 57/57D, the Cuota (Toll Road) south toward Monclova. Stop in Monclova if it’s getting late. If you still have plenty of daylight, you can probably keep going as far as Saltillo your first day.

Day 2, Saltillo to Queretaro, (still on 57/57D). Big city. Lots of hotels to choose from.

On Day 3, From Queretaro, head for Puebla, being careful to stay to the east of Mexico City, and from there, down the mountain through Orizaba to Cordoba. You could stop there; personally, I pushed all the way to Villahermosa on the third day, but that was probably a bit too much. In any case, you’ll pass through Villahermosa at some point, and from there, it’s a hop, skip and a jump to Merida, along the coast road. Stick to the toll roads (keep a stack of bills and coins handy for the tolls), and the trip should be a breeze.

Use a booking app to find lodging–the Mexican version of Expedia worked well for me, and I would imagine that the listings include the pet policy. It would be best to downplay the size of your dog when checking in to a hotel. Tell them you have a “perrito,” and let it go at that. (I speak from experience–I drove all over Colombia with a large dog 😉

Caravans? I’m not sure about that. Some of the auto clubs used to organize caravans, but I think most such groups are avoiding Mexico right now. At that, please do be careful on the road.

Weather is tough to predict, but you’ll almost certainly see rain in the southern part of the country. I had water up to the floorboards of my Jeep, driving through the streets of Cancun in an October rainstorm!

Good luck, and have fun!

Thank you so much for the info. We will take eagle pass. I got temporary import permit at the Mexican Consulate. Do we still need to stop at the banjercito for the visitor visa? I did the INM online for my husband and I. Thank you again. Terese