DAY 4: FROM VILLAHERMOSA TO PALENQUE

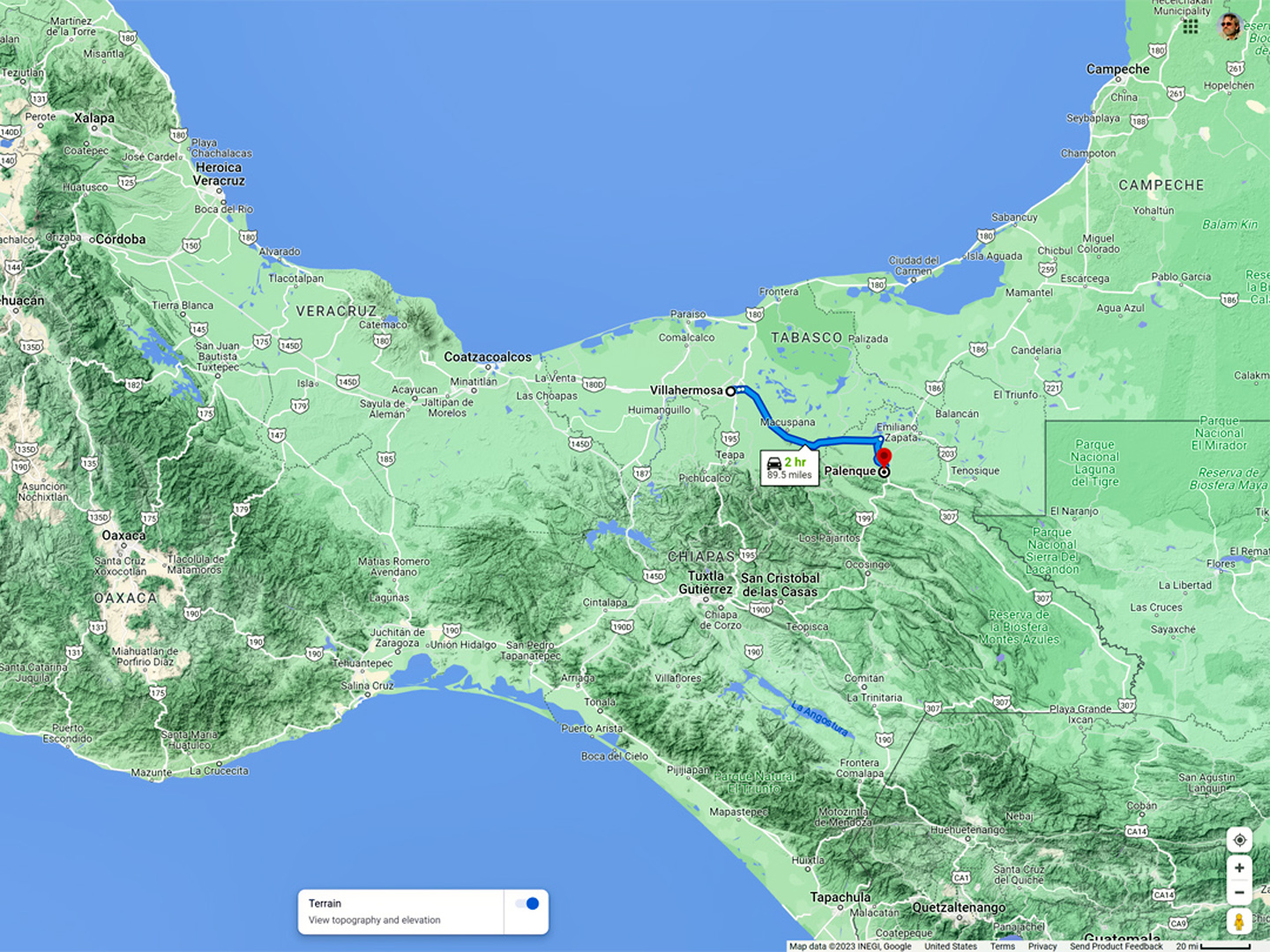

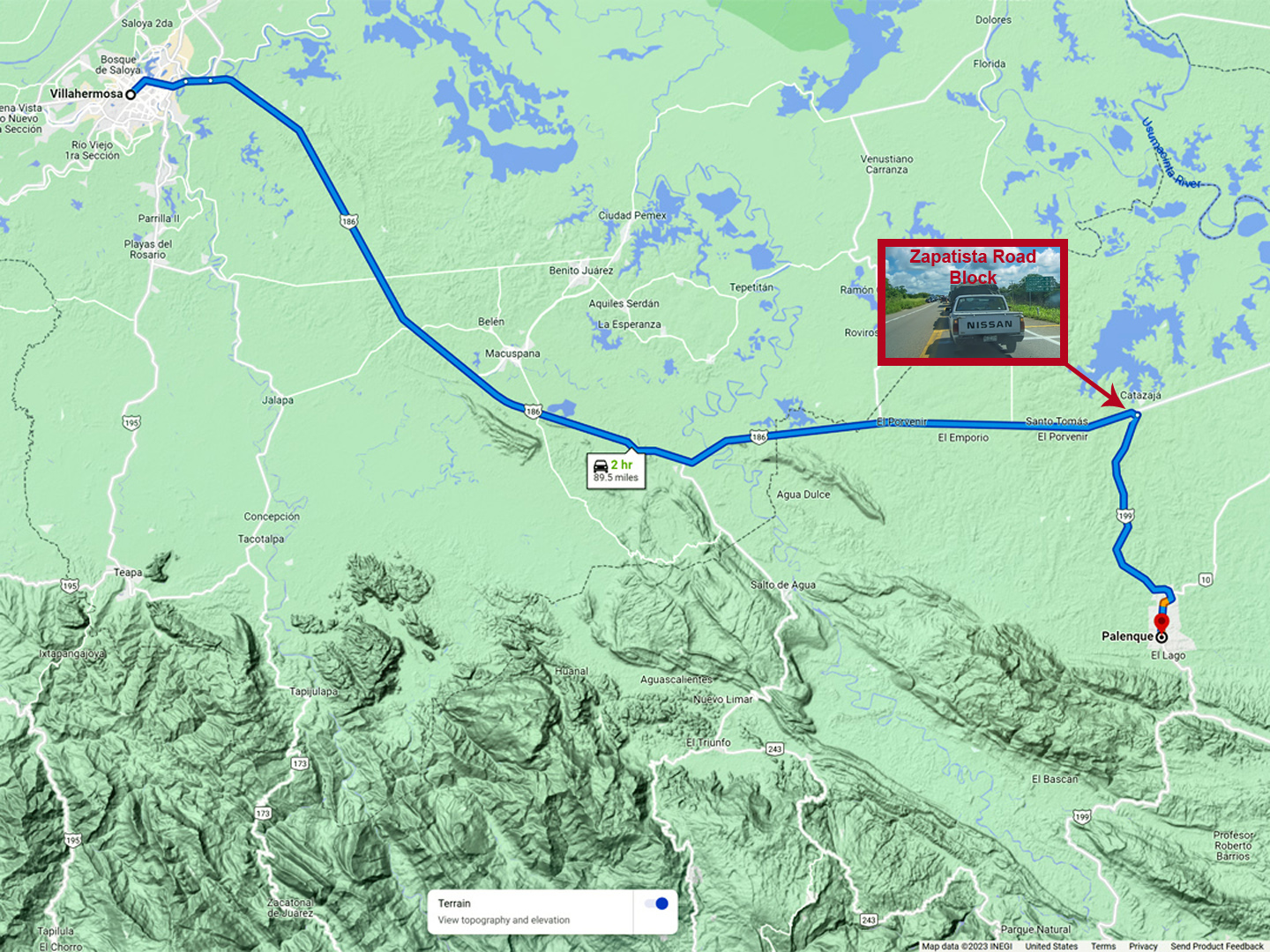

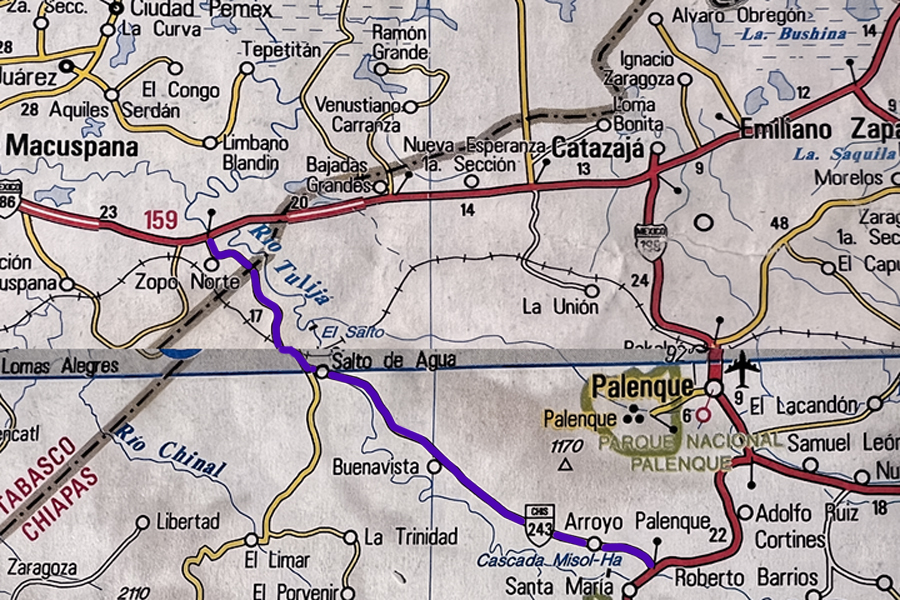

After three long days and more than 1,200 miles of driving, we’d made it from Laredo, on the border with Texas, all the way to Villahermosa, in the Mexican State of Tabasco. We stayed the night there, but we didn’t stick around long enough to check out the town. Palenque, our first official destination, was just two hours away, and we were anxious to get on the road! We hopped onto MX 186, the toll road, and drove east/southeast toward Catazaja and the intersection with MX 199, a distance of just 75 miles. From there, it was another 15 miles south to one of the most spectacular ancient cities in the Americas. Ancient ruins are my passion. This was my first trip to the land of the Maya, so I was looking forward to this day the way a kid looks forward to Christmas.

Villahermosa to Palenque, toll booth, and location of roadblock

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS TO EXPAND

We had smooth sailing the whole way, until just before we reached the road junction. That was where all the traffic came to a halt, a line of buses, trucks, and private cars that stretched out further than I could see. The truckers had all shut off their engines. Many of them had bedded down in the shade underneath their vehicles, and were taking an early morning siesta; some sat together in small groups, playing cards. Vendors were walking up and down the line selling sodas and other refreshments to the stalled drivers, and from the look of things, everyone was settling in for a long wait.

I asked one of the truckers what was going on, and he explained that this was a Bloqueo, a protest mounted by the Zapatistas, a group of indigenous political activists, and they were stopping all traffic on every road leading into the State of Chiapas. They apparently did this sort of thing on a regular basis. This time, they were protesting the proposed construction of a “Super Carretera,” a modern highway that would run from Palenque to San Cristobal de Las Casas. The existing road was dangerous, and notoriously slow. A new toll road would cut the travel time in half, enhancing commerce, improving safety, and attracting more tourists to the region.

The Zapatistas felt that a road like that would only benefit outside interests, to the detriment of local residents, and that it would degrade the natural environment. To call attention to their position, they parked several 18 wheelers sideways across the highway by one of the toll plazas, and refused to move them, bringing all traffic to a halt in both directions. The Federales showed up first, followed by a squad of soldiers. The opposing factions faced off against each other, the Zapatista commanders exhorting the crowd with bullhorns, and before long the news media arrived, undoubtedly hoping to document a lively head bashing and mass arrests.

That was about the time that Michael and I got there. We walked up closer to the head of the line, to see what we could see: soldiers and police with rifles, campesinos waving signs, and at least one television news crew. I asked someone how long it was likely to last, and was told that it would probably end at sundown. “But it could stretch out for two or three days,” they said. “You never know with these guys.”

I wasn’t about to spend even one whole day sitting in a traffic jam, no matter how much sympathy I might have for their cause, so that left us with two choices: Option 1: we could make a U-Turn and head back to Villahermosa, then take the coast road north into the Yucatan, saving Palenque for another day, or: Option 2: see if we could find a back road to Palenque that bypassed the Zapatista Road Block.

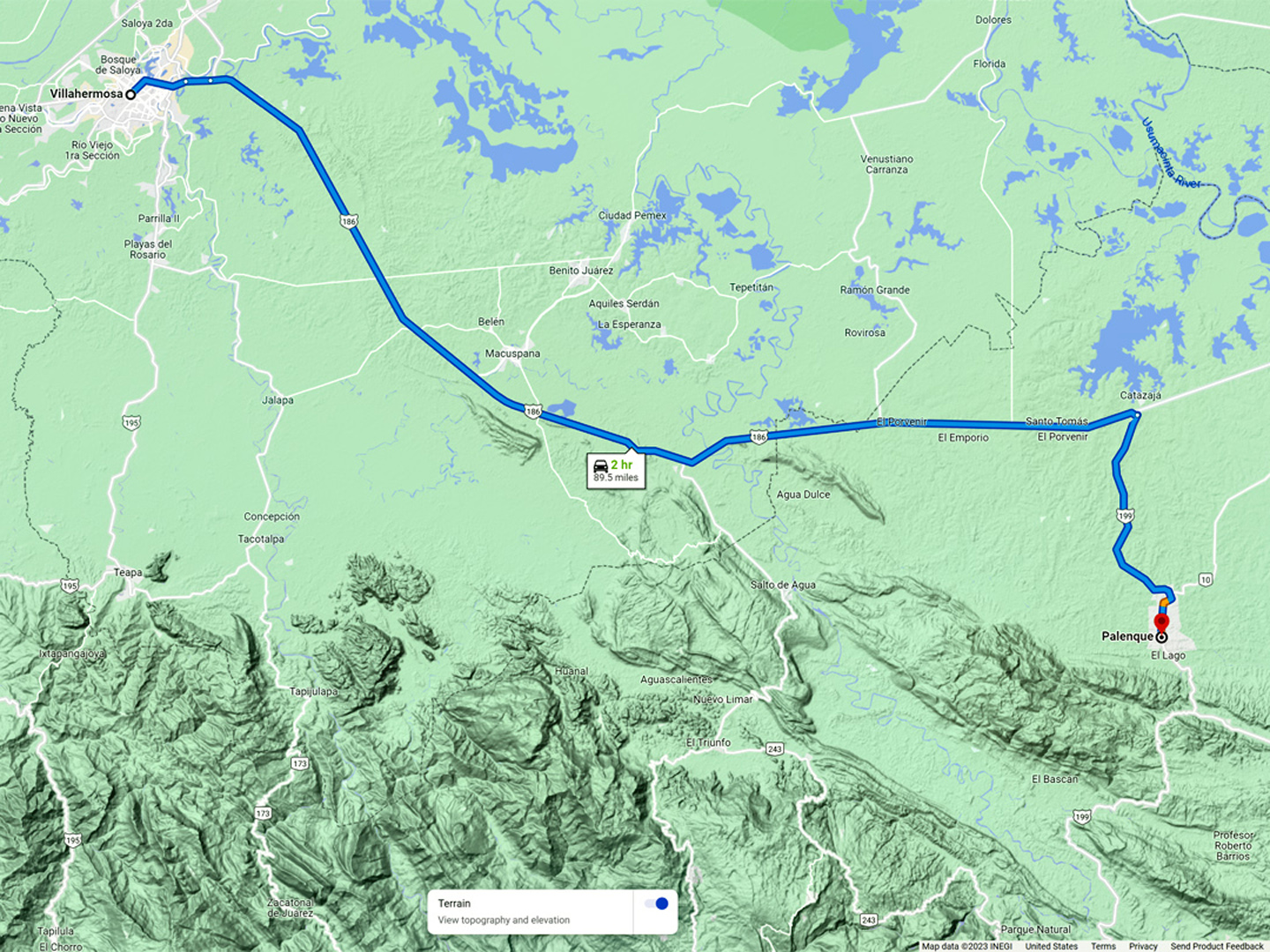

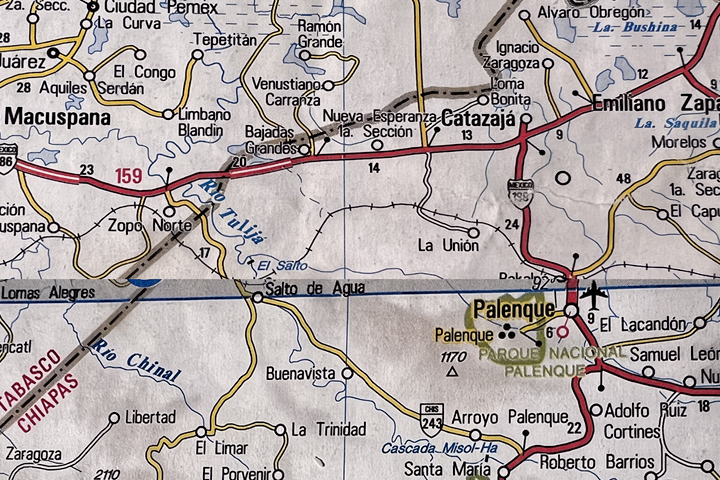

I had a spiral bound copy of the Guia Roji, a Mexican road atlas that’s a bit like Rand McNally. I turned to the page with a map of the area around Palenque, located the highway intersection where they’d put up the road block, and then traced backwards along MX 186, looking for an alternate route–and I actually found something! There was a State Highway, #243, that intersected MX 186 about 25 miles back toward Villahermosa.

Route 243 crossed the line into Chiapas just before reaching a town called Salto de Agua (Waterfall), about five miles from the main highway. From there, it continued southeast through the countryside, and connected with MX 199 forty miles south of Palenque. It was marked as a secondary road, so it was probably paved, and since we’d already decided not to wait where we were, I figured we had little to lose. “It’ll be an adventure,” I said to Michael. As it turned out, truer words were never spoken!

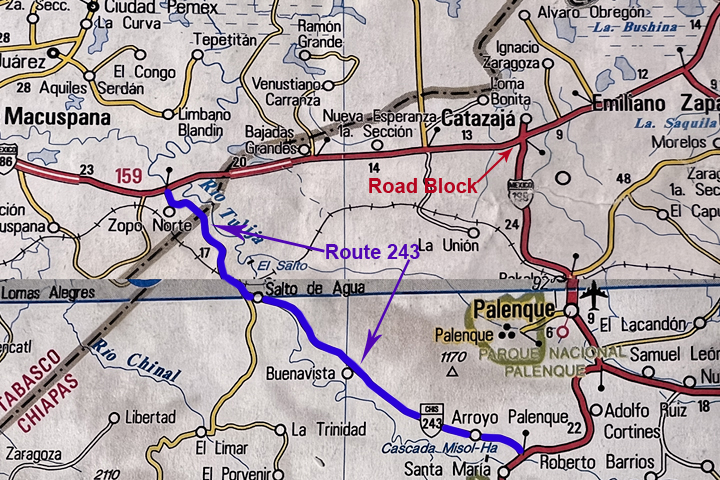

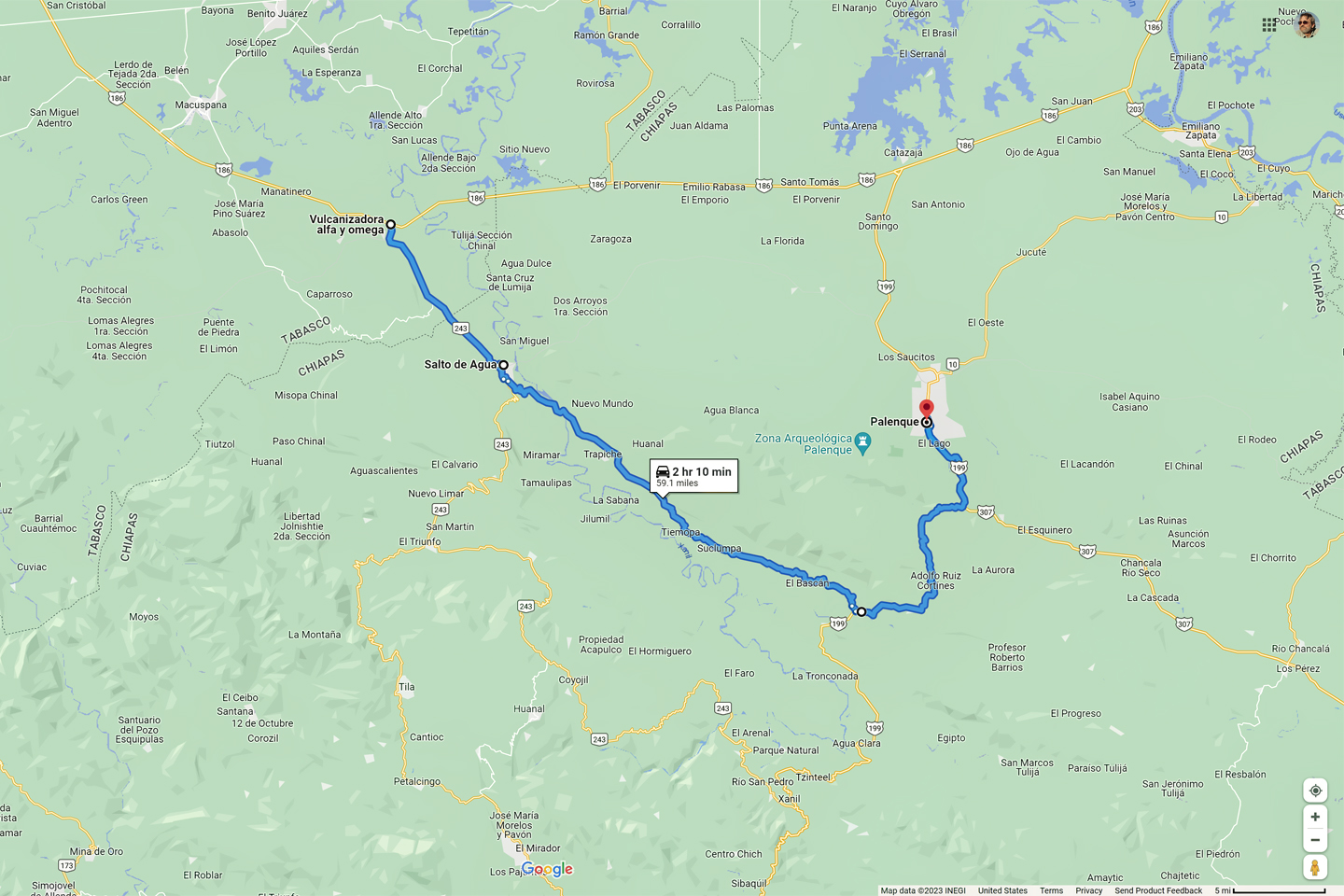

I had no reason not to trust the Guia Roji, but since I had a decent signal on my smart phone, I figured it would be wise to double check that back road using Google Maps. I found State Route 243, but when I tried to match it with what I was seeing in my road atlas, it appeared as though Guia Roji’s map artists had smoothed out some serious curves. The road began and ended in the right places, but the countryside in between was something else again! The distance to MX 199 was 75 miles, and Palenque was 42 miles further. According to Google, I’d need a bit more than 5 hours to drive it. That’s a very slow road, barely averaging 20 mph, with one switchback curve after another!

Route 243 to Palenque, in the Guia Roji, and on Google Maps. Also: the shortcut we discovered, using smaller roads that don’t appear in the road atlas

One nice thing about Google Maps is the way it lets you zoom in to view an area in greater detail. When I zoomed on the little town of Salto de Agua, I spotted yet another road, this one even smaller, that seemed to be a shortcut, connecting Route 243 with MX 199 in half the distance, and requiring less than half the time. This road didn’t appear at all in the Guia Roji atlas. I’d been burned by Google Maps enough times to to be cautious: the mystery shortcut might be nothing more than a cart track, or a footpath, in which case I’d have to stick with Route 243. Either way, the first step was to drive to Salto de Agua. Once we got there, the locals would know the best way to go.

MX 186 was a major regional highway that carried a ton of traffic; the line of vehicles backed up behind us had grown by almost half a mile, just in the time we’d been stopped. Many drivers were turning around and going back the other way, so I made a U-turn, and joined the pack. I assumed that there would be plenty of other drivers with the same idea as me, but when we got to the junction with Route 243, ours was the only vehicle that slowed and made the turn. It was a smaller road than what I expected, so small we almost missed it. Calling this road paved was a serious stretch: half the asphalt was missing altogether, and the rest had potholes big enough to cause damage. We bumped and bounced our way past a sign that read, “Welcome to Chiapas.” That was encouraging! Nobody was trying to stop the traffic on this road–it wouldn’t be worth their time.

We reached Salto de Agua, and almost immediately came to an unmarked fork in the road. This was the point where we were going to need some guidance, so I looked around, and spotted a policeman, standing on the corner. He was staring at us, obviously curious, so I turned around, and drove over beside him.

“Good morning,” I said cheerfully. “Can you tell me which of these roads is the best way to Palenque?”

“Palenque?” he said, looking a bit perplexed. “You should go back to the main road. That’s the way to Palenque.”

“The main road is closed today,” I informed him. “Nobody is moving past the crossroads.”

“Ah. The Bloqueo. But even so, that’s the only way to Palenque. You’ll have to go back the way you came.”

“My map says that this road goes on to Palenque.” I opened up the atlas and showed it to him, explaining about the long way around on Route 243, versus the shortcut I’d found on Google Maps. “I’m wondering if it would be possible to get through on the small road. It’s not on my map, but it would be right alongside the river, just north of it.”

The policeman studied the lines on the map, tracing them with his finger, looking even more perplexed “Yes,” he admitted with a shrug. “It is possible, but you really don’t want to go that way. It’s a terrible road!” He said something else after that, but I didn’t quite catch it, and besides, he had me at “terrible road”. I drive a Jeep, after all, and I love a challenge!

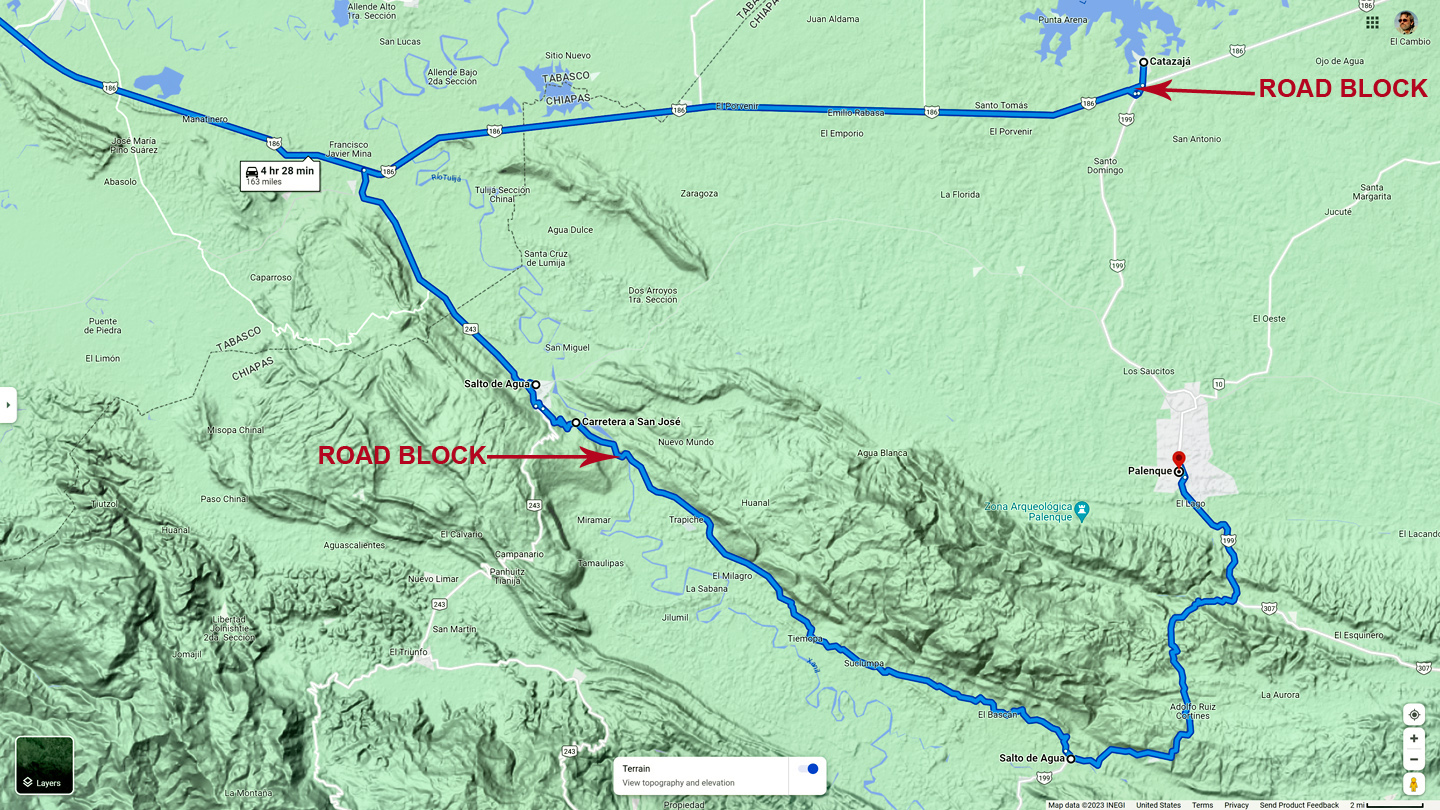

Shortcut from Salto de Agua to MX 199, and an unexpected road block

The guy wasn’t kidding about the road. The first couple of miles were paved, because we were still in the town, but after that, it went to the dogs, with wheel ruts so deep, it was like driving across a plowed field. According to Google Maps, the road followed a river. We hadn’t actually seen it yet, but we were supposed to be crossing it on a bridge at any moment. We rounded a curve, and sure enough, there it was, but there was a gang of guys with machetes who seemed to be waiting for us, and they had a chain stretched across the road, blocking the way.

“More Zapatistas?” Mike asked.

“If we’re lucky,” I replied. “If it’s anybody else, we’re in serious trouble.” I drove slowly up to the roadblock, and lowered my window.

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

I didn’t like the sound of that. Not at all, so I gave him a blank look and said, “No entiendo.” (I don’t understand).

“No entiende?” he repeated back to me. He wasn’t quite sure how to respond to that.

“How about you take ten Pesos,” I said in English, pressing a large, gold-colored coin into his hand. He stared at the coin, worth about 60 cents. It was such a ridiculous offer, he couldn’t decide if he should laugh in my face, or chop off my thumbs. The other guys took his uncertainty for acceptance and dropped the chain, so we sped away across the bridge, before they had a chance to reconsider.

There followed more than two hours of incredibly slow going over what really was a terrible road, but it was beautiful, and driving it was great fun. This was the most rural area we’d been through yet, tiny subsistence-level farms, so far off the grid, it was like observing life in a previous century. The only connection with the modern world was the road, which remained terrible for its entire length. When we finally got to the other end, just before we rejoined the paved highway south of Palenque, we ran into another roadblock! The Zapatistas weren’t done with us yet.

Scene along a rural road in northern Chiapas

Board with nails, crude but effective way to stop traffic at a road block

At this road block, they had a long board with nails driven through it from the bottom side, and they’d laid it across the width of the road. We slowed down as we approached, and watched as they pulled their board back to allow a small local shuttle van to pass. Those little vans were the only transportation available to local residents, and they were apparently allowing them through the blockade. I saw that as an opportunity: while the van scooted past the stop point headed west, I shot around them headed east, just barely making it past as they attempted to jam their board full of nails under my tires, loudly yelling at me to stop. Needless to say, I kept going!

We made it to Palenque about half an hour later, found ourselves a room, and headed for the famous Mayan ruins on the outskirts of the town. With all the roads to the outside world sealed off by the Bloqueo–even the smallest roads, as we’d discovered–the only visitors to the archeaological park that day were people who were already there in Palenque before the roadblocks went up, a small fraction of the usual number of visitors. When we pulled into the parking area by the ruins, we attracted a curious crowd, and one of the men asked how we’d gotten through.

“We took a back road,” I told him.

“You found a road with no bloqueo?”

“There was a small bloqueo,” I replied. “But they let me pass when I paid the toll.”

He laughed, but then he quizzed me about that, wanting to know how much I’d paid, and on which road, and I realized that he might be some sort of Zapatista organizer, trying to figure out which of their people had failed at his job. I really didn’t want to get the guy at the road block into trouble, so I was deliberately evasive, claiming that I was lost out there, and didn’t even know which road I was on. He didn’t much like that answer, but he didn’t press me any further. Running those roadblocks provided one heck of an adrenaline rush, but, in hindsight, it was more than a little foolish. We were extremely lucky that it didn’t end with punctured tires, if not punctured torsos. The Zapatistas are a serious organization with serious concerns. We were in Chiapas, which is their turf, so I really should have shown more respect. The wise move, under these circumstances, would have been to simply leave the area, and find somewhere else to go until the protest ran it’s course, and the road opened once again.

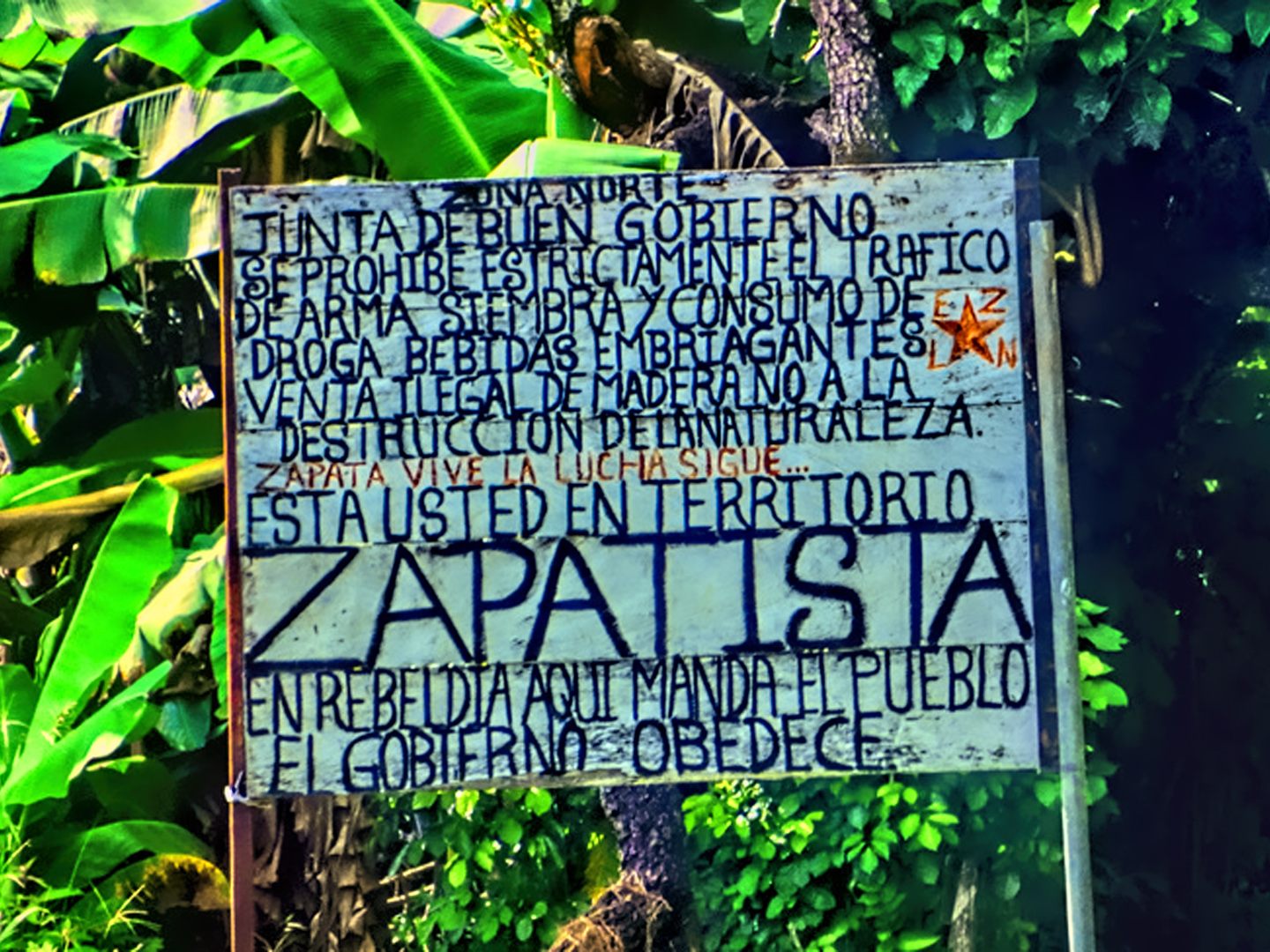

THE ZAPATISTAS!

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (ELZN) is a militant political organization that has controlled most of the Mexican State of Chiapas for most of the last thirty years. They’re named after Emiliano Zapata, the commander of the Liberation Army of the South during the Mexican Revolution, and a great hero to the country’s poor. Their primary focus is on the rights and well being of the region’s downtrodden indigenous people, many of whom are of Mayan descent.

A sign alongside the highway reads:

Northern Zone: Good Government Board:

We strictly prohibit weapons trafficking, planting and consumption of drugs and intoxicating beverages, illegal sale of wood, and the destruction of nature!

Zapata lives, the fight continues

You are in Zapatista Territory!

In rebellion: here, the People rule, and the government obeys

They’ve been at war with the Mexican government since 1994, using civil disobedience as their primary tactic. They’ve been described as Marxists, Socialists, and Anarchists, though in truth they can’t be so simplistically classified. For decades, they watched in silence as wealthy landowners treated them like serfs, and sold off their minerals and the valuable hardwood trees in their forests to careless profiteers who caused great harm to the environment. The Zapatistas quite simply want to regain control of their land and its resources, land that has rightfully belonged to their people for more than 2,000 years! The group’s most active period was in their early days, back in the 1990’s when they took over several towns in Chiapas, including San Cristobal de Las Casas. In subsequent years, many of their most prominent leaders were hunted down and jailed, but more recently, the government’s stance has softened. These days they’re tolerated, if not accepted as a legitimate voice for a large segment of the population in the southernmost part of Mexico.

Michael and I visited the ruins of Palenque twice: the afternoon of the day we arrived, and again the following morning, always the best time of day for photographs. When we’d finished at the archeaological park, we drove 13 miles south on MX 199 to Misol-Ha, a beautiful waterfall in the Lacandon jungle.

The Mayan City of Palenque

Misol-Ha, a waterfall in Chiapas

It was barely past noon when we finished exploring Misol-Ha. When I studied my map, I saw that San Cristobal de Las Casas, a place I definitely wanted to see, was only 100 miles away. A hundred miles? Heck, even on a slow mountain road, that should only take three hours at the most! Or so I thought. That stretch of highway is heavily used by trucks and buses that are often dangerously overloaded. The road consists of one steep curve after another; those heavy trucks are doing quite well if they hit 10 mph on the upgrades, and 15 mph rolling downhill in compound low. There are no passing lanes, nor is there much point in even trying to get ahead of the pack, since every vehicle on the road is equally slow. A hundred miles on THAT kind of road takes closer to six hours, and it’s exhausting!

The highway went through the middle of every small town along the way, which meant slowing down even more for speed bump after speed bump, all the while dodging potholes and free ranging chickens and goats. In one tiny community, we slowed for a group of children trying to sell us some sort of fruit, portioned out in plastic bags. We noticed that a young girl standing just ahead of the others was holding a string that she’d tied to a tree on the far side of the road. When she saw us approaching, she pulled her string taut, and raised her other hand, which was holding a bag of fruit, and shouted for us to stop.

Her string obviously wouldn’t have stopped us if we’d elected to keep going, but I didn’t want to spoil their game, so I told Mike to stop just short of it, and I rolled down my window.

“Buenas tardes,” I said. “Can I help you?”

“You must buy these guavas,” said the girl.

“I don’t want them,” I replied. “I don’t like guavas.”

“If you don’t buy, you must pay the toll,” she said, her face very serious.

“How much is the toll?”

“One Hundred Pesos.”

“That’s ridiculous,” I replied. “I won’t pay it.”

She stepped closer, peering through the passenger-side window, taking stock of the cameras and other expensive equipment cluttering the front seat. “Five Pesos, and those gafas.” Mike was wearing a pair of Ray Bans worth at least a hundred bucks. Clearly, the young lady had taste!

I handed her a ten Peso coin, the same amount I’d paid the young Zapatistas the day before. She scowled, but she dropped her string, and we drove on toward Ocosingo, a town near the halfway point between Palenque and San Cristobal. I was beginning to wonder if we would EVER get where we were going, but right about then, all the traffic on the highway came to a halt, stopped dead, all the way through the town.

I pulled over to the side of the road, and one of the truck drivers walked over and greeted us. This was another Zapatista Bloqueo, he explained, and this time, they were stopping all traffic headed to San Cristobal de Las Casas! The trucker chatted with us for quite awhile, and he was definitely passionate about his grievances.

It would seem that support for the Zapatistas and their road blocks is far from universal. When the movement first began, back in the ’90’s, most of the people were in favor of what they were doing, but after so many years with no real change, sentiments have been shifting. A lot of people in the region make their living, in one way or another, from the transportation of goods. Not just the truckers, but the farmers, the shop keepers, ordinary people who have nothing to do with the Zapatistas and their politics. Many other people are dependent on the tourists, and when the roads are blocked to keep them out, everyone loses badly needed income. There’s also a lot of mistrust, a widely held belief that the Zapatista leadership is cutting back room deals with the government, and lining their own pockets, at the expense of everyone else. These are complex issues, and they are ongoing: the events in this post took place in 2015, more than eight years ago, and according to current reports on the news media, as well as social media, very little seems to have changed.

We bade goodbye to our trucker friend, then we turned around and drove back to Palenque, where we spent a second night with the toucans at the Comfort Inn.

The idea of blocking the roads to stop traffic has become a part of the culture in the hills of Chiapas, and anyone driving through the area stands a good chance of encountering one of these bloqueos. When it’s the Zapatistas, you’ll be obliged to stop, because nobody gets through until the protest has ended. When it’s children, or villagers blocking your way with a string, a rope, or a chain, the easiest course of action is haggle them down to a reasonable fee, and pay them.

Next up: Mexican Road Trip: Days 4-5: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

(Unless otherwise noted, all of these images are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.)

READ MORE LIKE THIS:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

MEXICAN ROAD TRIP: HOW TO PLAN AND PREPARE FOR A DRIVE TO THE YUCATAN

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancun, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancun from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

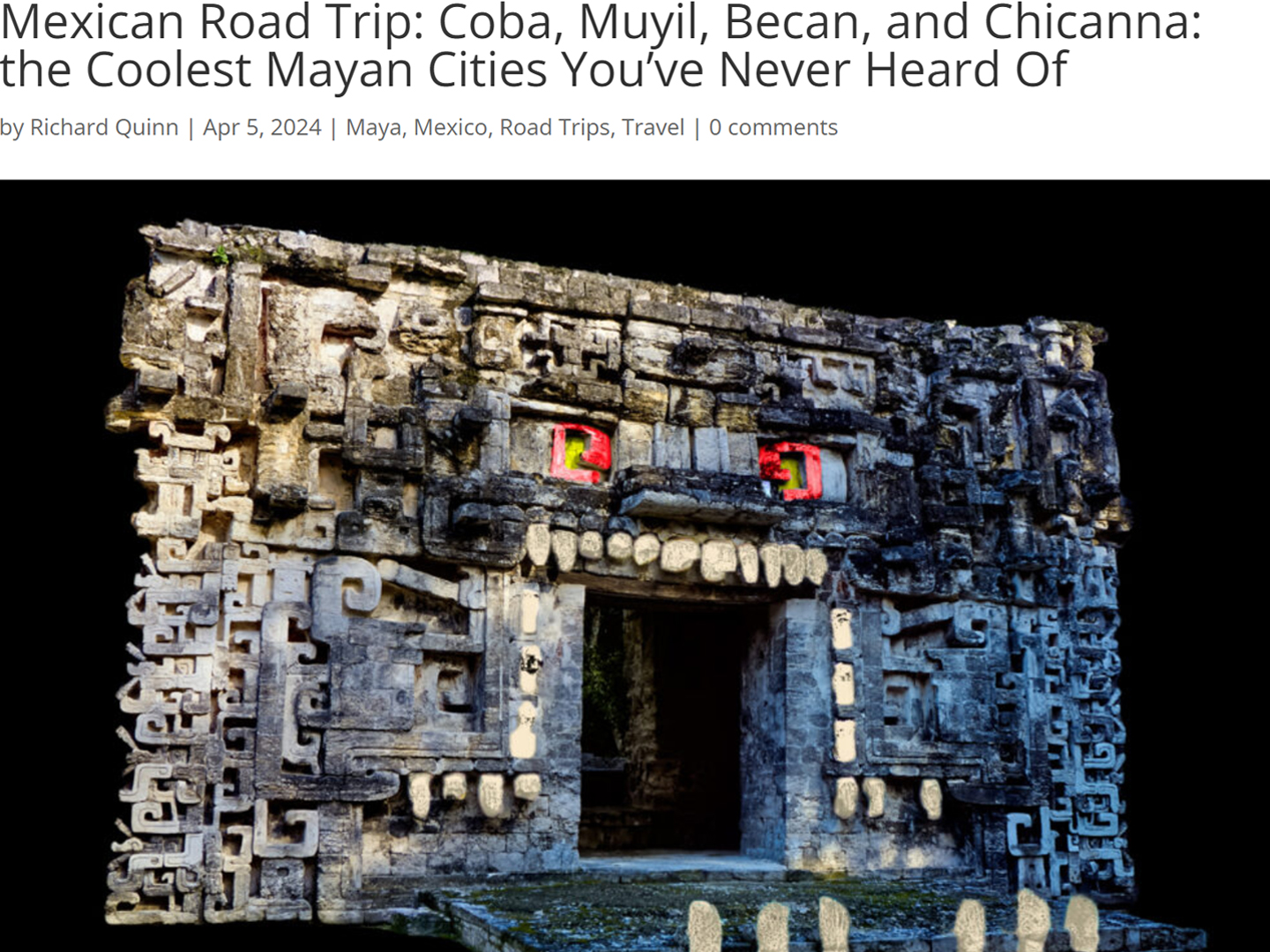

Mexican Road Trip: Cobá, Muyil, Becan, and Chicanna: the Coolest Mayan Cities You've Never Heard Of

After Tulum, we drove south, then west, headed back to Campeche. Along the way, we visited some Mayan ruins that are less well known, starting with Cobá. the major Mayan city northwest of Tulum, followed by Muyil, Becan, and Chicanna. Each site was unique, and each of them added another piece to the puzzle of the ancient Maya.

(This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication: April, 2024)

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Campeche, Edzna, and La Guaranducha

(This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication: May, 2024)

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico's Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they've adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It's a wonderful, colorful parade that's all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I've ever seen. There's a powerful energy in that spot--maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps--but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I've ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I've ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Photographer's Assignment: Chichén Itzá

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Cobá and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Cobá was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Becan and Chicanna: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

A shout out to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. "Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins" was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after "Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali." We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Road trips with old friends are the absolute best. We laugh and we laugh until we run out of breath, and laughter is good for the soul!

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments