Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan cities go, but its spectacular location, right on the Caribbean coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque. This was a late post-classic Maya site that was at it’s peak from 1200 AD right up to the time of the Spanish Conquest. It was still inhabited for at least 70 years after the arrival of the Europeans, until the Old World diseases brought along by the Spaniards took hold and decimated the population, causing the town to be abandoned.

Today, the ruin is home to a motley assortment of Spiny Tailed Iguanas, and if you visit when it’s busy, to brightly colored herds of tourists, taking a day trip from Cancun, or one of the many other resorts along the Riviera Maya. Tulum is easily accessible to the millions of beach loving vacationers that come to the area every year, and that, more than anything else, makes it one of the most popular Mayan ruins in the Yucatan, second only to the world famous ancient city of Chichen Itza.

Iguanas take over when the tourists depart, so the abandoned city is never entirely empty.

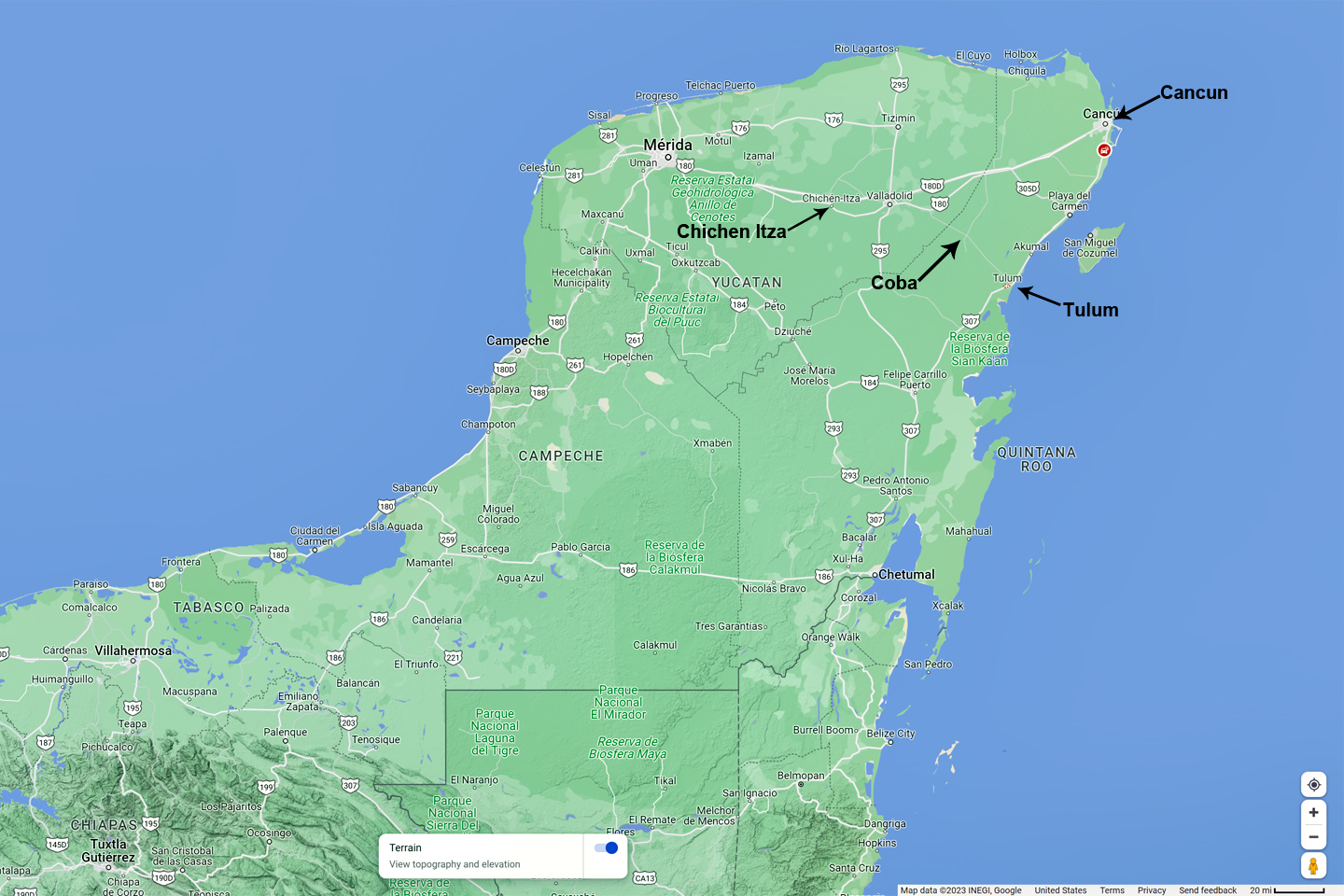

The location of Tulum, relative to Chichen Itzá, Cancun, and Coba

Click maps and photos for an expanded view

HISTORY OF TULUM

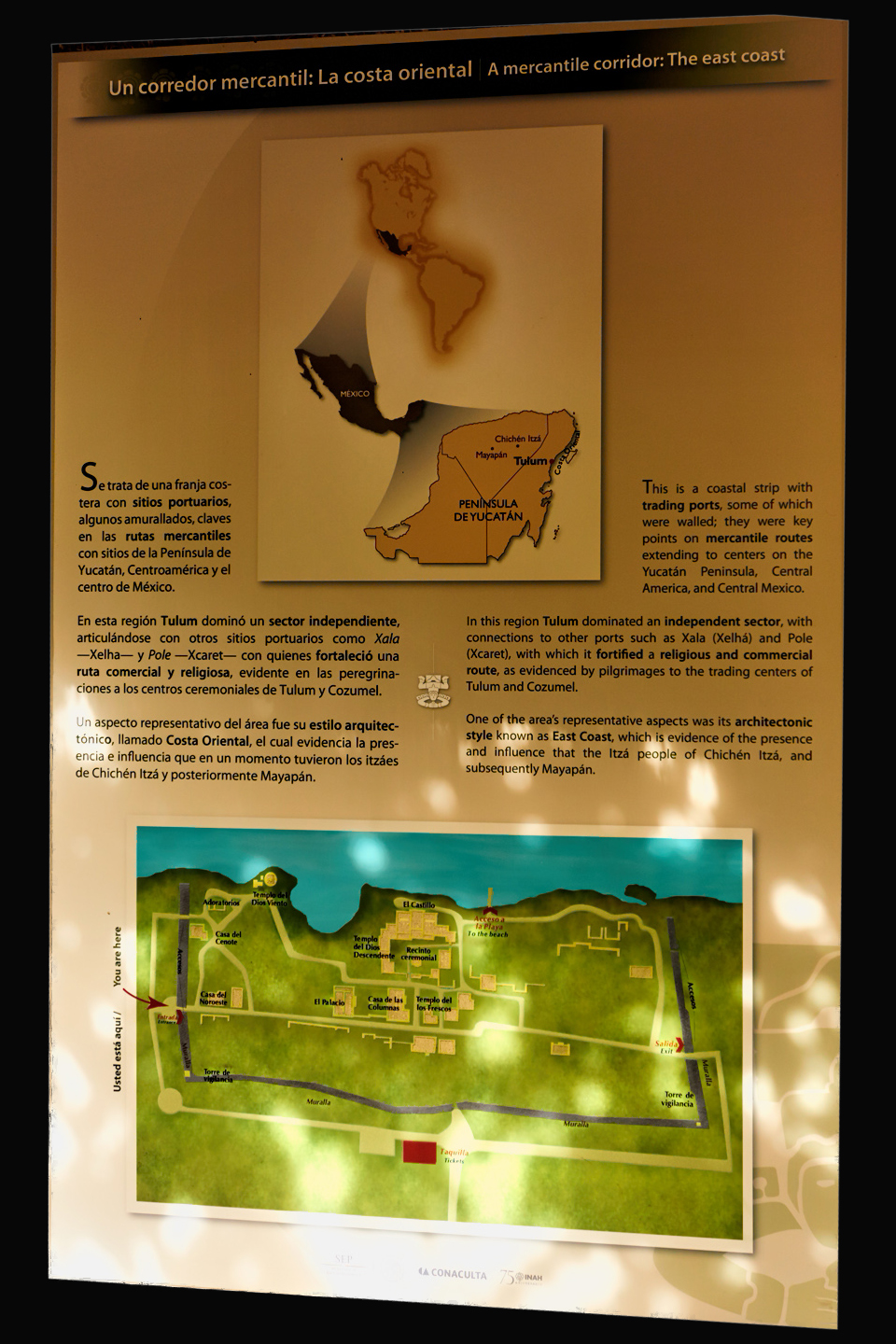

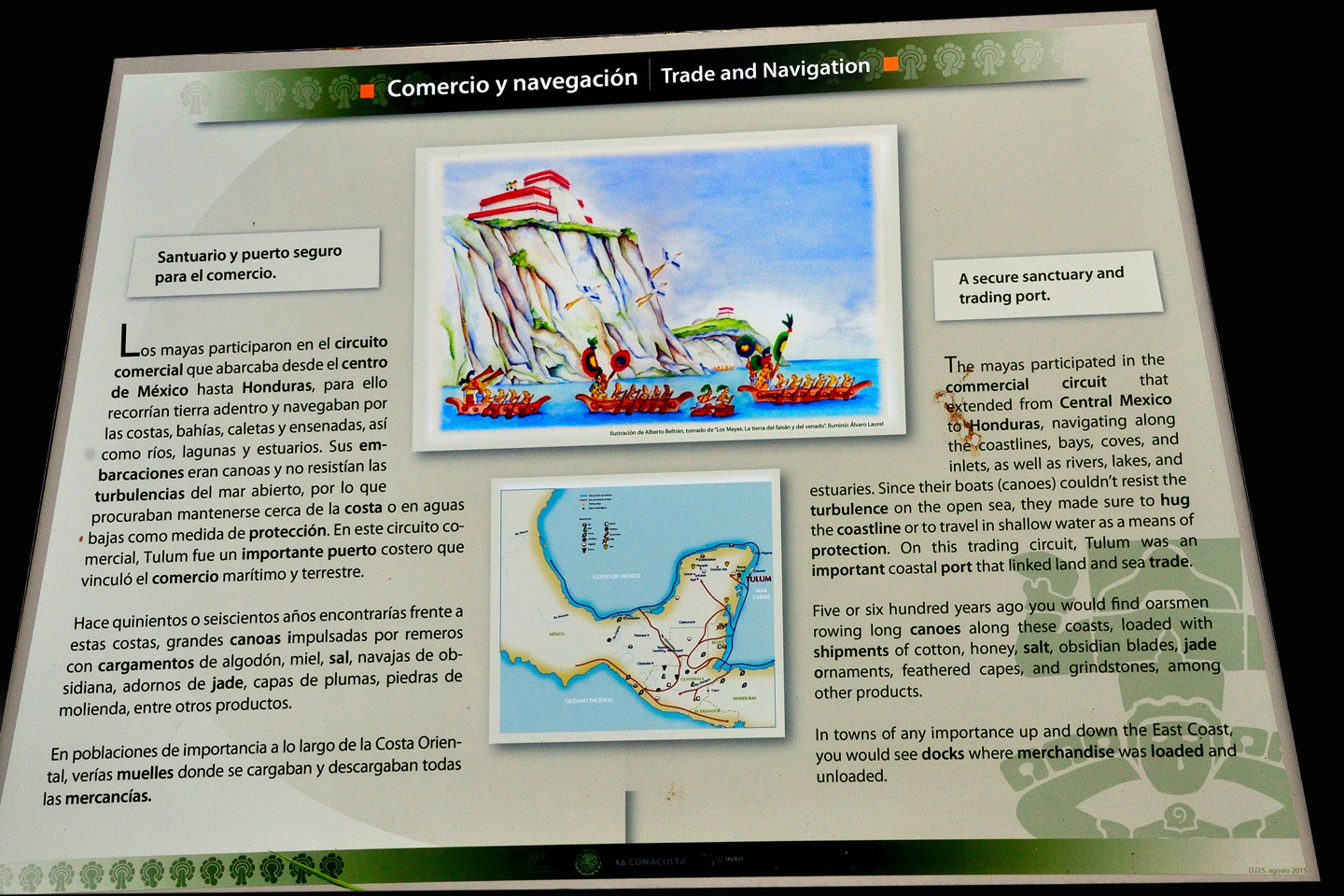

In the Yucatec Mayan language, Tulum means enclosure, or wall, but scholars believe that’s a modern name. It’s thought that the original name may have been Zama, which means dawn, in reference to its location on the eastward facing coast. Tulum was in fact a walled city, built for easy defense, perched on ocean-side cliffs nearly forty feet high. This fortress-like town of perhaps 1500 inhabitants served as the port for Coba, a much larger Mayan center that lay inland, 27 miles to the northwest. There was a significant volume of coastal trade in the ancient Americas. Large seagoing canoes followed routes that hugged the coastline from the Gulf of Mexico, around the Yucatan Peninsula to the Caribbean.

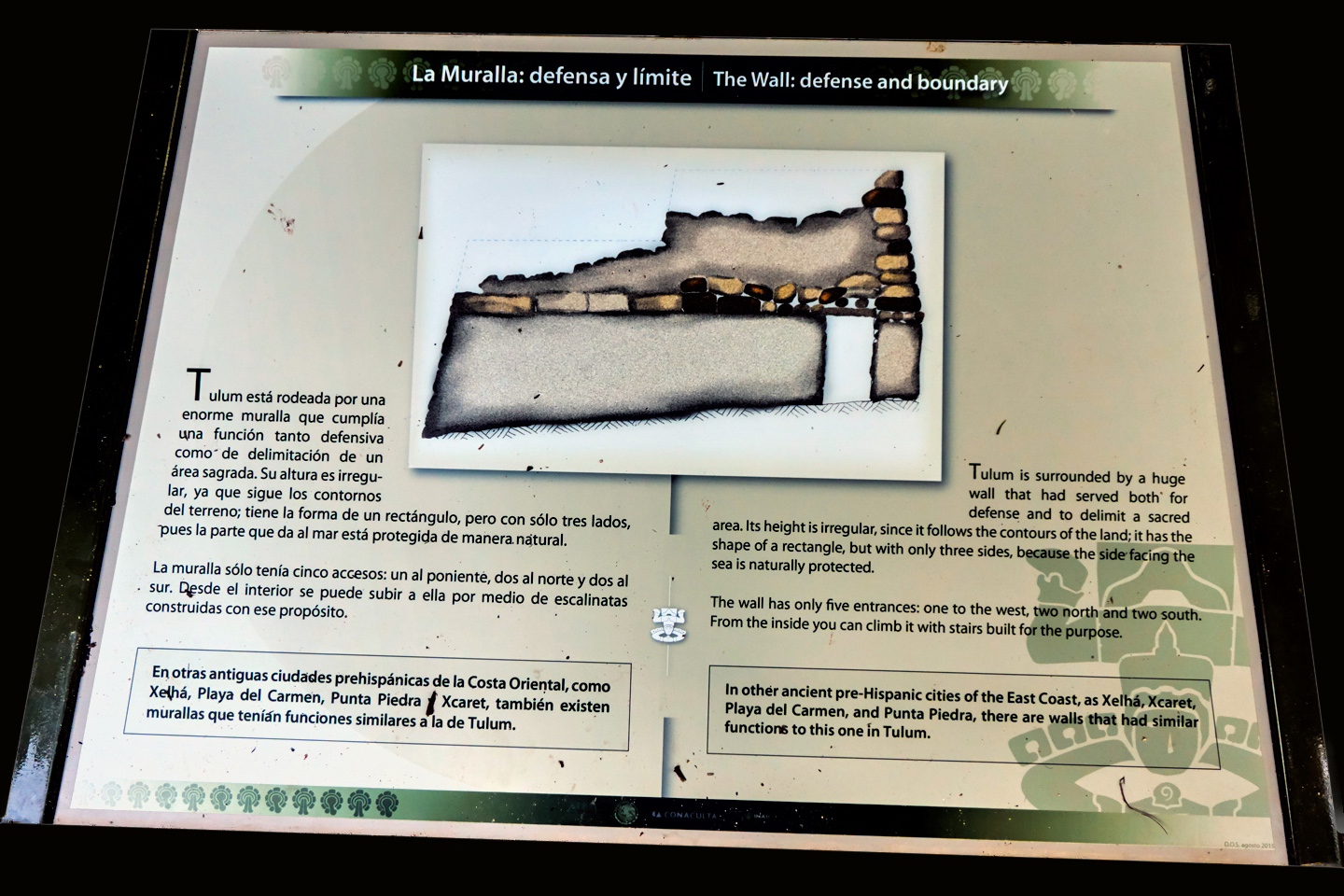

A reconstructed section of the boundary wall that once surrounded the city of Tulum, keeping out any invaders, and separating the common people from the elite: the nobles, priests, and wealthy merchants.

The traders carried mostly low density, high value trade goods, things like jade, turquoise, and feathers from rare birds, as well as more utilitarian items like salt, obsidian, and honey. Dried cacao pods were a special commodity, often used as a form of currency. There was also trade in ideas, construction techniques, and artistic styles, which helps to explain some of the similarities between disparate cultures that were separated by significant distances.

PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN

Tulum was one of many ports and trading centers serving the vast territory of the ancient Maya. The elite class of nobles and priests who ruled those lands had an abiding fondness for the finer things, so the trade in such items was brisk, and quite lucrative. Without wheels or pack animals, anything transported over land had to be packed on the backs of porters. Such men braved significant hardships, crossing rugged mountains and dense jungles, fording rushing rivers, and defending themselves from any hostiles who might attempt to hijack their cargo.

The coastal trade routes were much more efficient, as they used large, seagoing canoes with as many as a dozen paddlers, capable of carrying far more weight over greater distances. Ports like Tulum became storehouses as well as distribution points for the elite luxury goods that arrived in a steady stream. Whenever significant wealth is concentrated in one spot, it tends to bring out the worst in human nature, so before long, it became necessary to fortify the larger trading centers. Tulum was protected by forty foot cliffs on the seaward side, and by a wall that surrounded the rest, so the defenders had a decided advantage against any attackers.

The trading canoes that carried valuable cargoes were defended by warriors armed with the weapons of the day, but a boatload of men with spears is far more vulnerable than a walled city defended by well-prepared fighters. There is no direct evidence of seagoing piracy during the Mayan era, but the temptation would have been hard to resist, and the fact that the canoes are so often depicted with guards is a good indication of an ongoing threat. Pretty cool, when you think about it. The original Pirates of the Caribbean were almost certainly Mayans, and if so, they would have predated Captain Jack Sparrow by half a millenium!

Mayan trade commodities, and the routes followed by traders on both land and sea. Coastal trade was by far the most efficient.

It is commonly believed that the port cities were controlled by the larger Mayan centers that lay further inland; that the nobles in charge of Tulum, for example, were underlings, subservient to the Lords of Coba. According to one theory, the trade wasn’t really trade at all, because everything went in one direction, like a pipeline that supplied, not water or oil, but luxury goods, all bound for a single destination. According to another theory, the coastal Maya were an entirely different people than the inland Maya, historically, culturally, even physiologically, and that they controlled the flow of trade, ultimately for their own benefit. The trading relationship between the ports and the inland cities is well documented; what’s not entirely clear is the pecking order. Who was actually in charge?

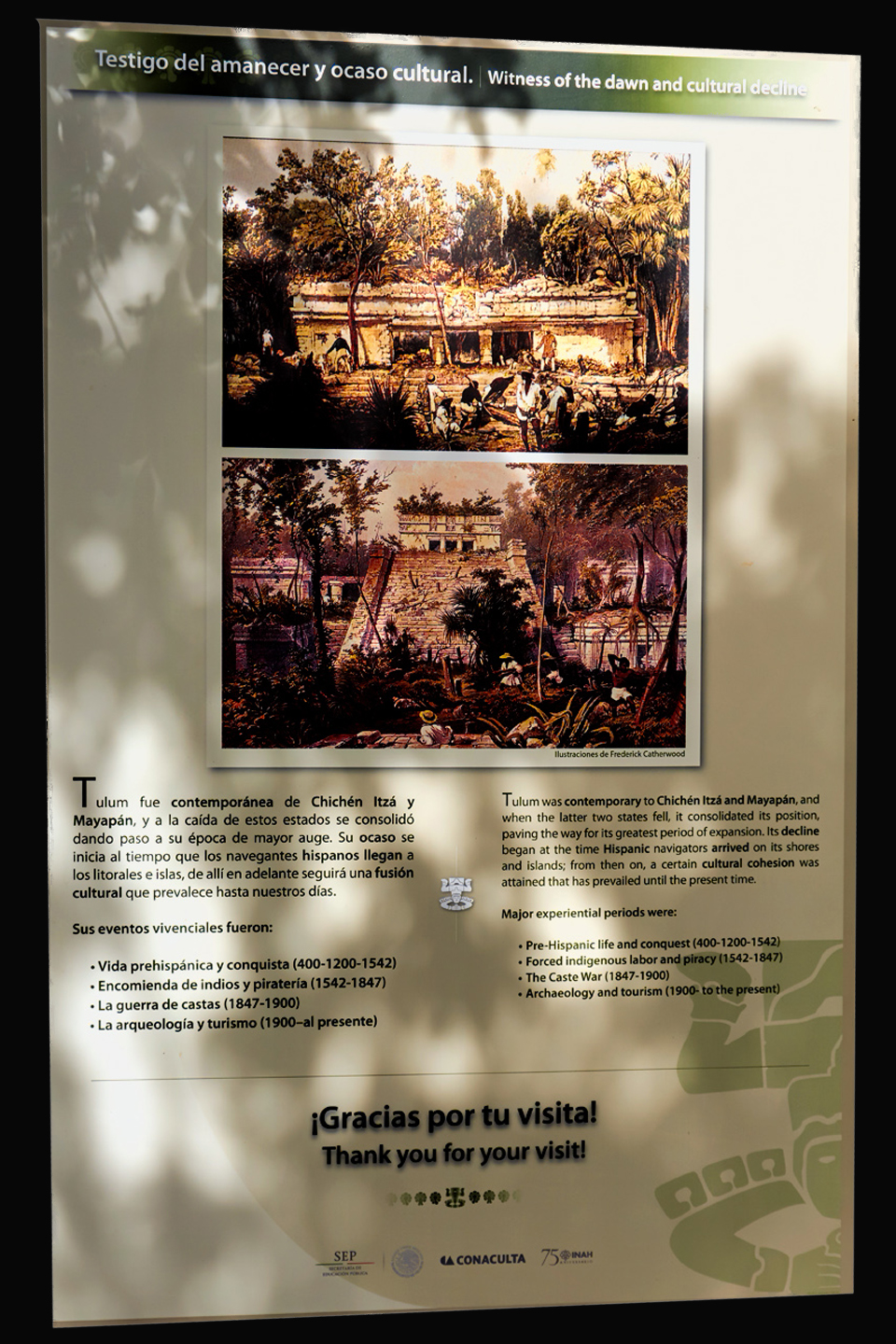

The Castillo at Tulum, an illustration by Frederick Catherwood from the book, Incidents of Travel in Yucatan. The drawing shows workmen in the process of clearing off the building, as it would have apeared in 1841.

Tulum was never “rediscovered,” or stumbled upon, like so many other Mayan sites, because it was never lost. It’s one of the few Mayan cities that was still in use when Europeans first arrived in the area. After it was abandoned, the tropical vegetation enveloped the stone structures, but they never disappeared from view because the Castillo, the site’s largest building, is perched on a prominent bluff overlooking the coastline. It was put there to serve as a landmark, clearly visible from the sea, and so it is. Spanish Captain Juan de Grijalva’s expedition sailed past Tulum in 1518, and in his words, it was “a village so large that Seville would not have appeared larger or better.”

The American writer John Stephens and his illustrator, Frederick Catherwood visited Tulum on their second expedition to the Yucatan in 1841, which they documented in Stephen’s book, a two-volume set titled Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, first published in 1843. This set complemented his earlier work, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan, which had been very well received in Europe, as well as in the United States. Catherwood’s meticulous illustrations of the ruined cities, the stelae, and the mysterious glyphs were the revelation that brought the ancient Maya to the attention of the outside world. The buildings in those drawings were clearly the product of an advanced civilization, previously unknown, yet possessed of artistic sensibilities and architectural expertise on a level with that of the ancient Greeks. The implications were staggering, and the source of much spirited debate among the intelligentsia of the mid-19th century.

Famed archaeologist and Maya expert Sylvanus Morley, the original real-life Indiana Jones, did preliminary excavations at Tulum beginning in 1913. Additional work was funded by the Carnegie Institution from 1916 until 1922, followed by a series of investigations in every decade through the 1970’s. When the developers who created Cancun opened for business in 1974, the surrounding area saw a flurry of growth that turned the archaeological site of Tulum into a bonafide tourist attraction. With the further development of the Riviera Maya, Tulum, the charming beach town adjacent to the ruins became a destination in its own right.

When you see a Mayan city in person, you can’t help but wonder what happened to the people who built it. The Mayan civilization was wondrously complex, and it flourished in this region for two thousand years. How is it possible for something like that to just disappear? Answer: it didn’t. At least, not all at once. The large inland cities were abandoned, largely by attrition, when an extended drought in the region caused crop failures that led to mass starvation. Tulum, and most of the smaller Mayan communities that were still occupied when the Spaniards arrived were exposed to the diseases brought from Europe; they had no natural resistance, so, once again, many of the people died. The survivors spread out through the area, eking out a meager existence as simple subsistance farmers, living in scattered hamlets and homesteads. Their numbers were greatly reduced, but the people were still there, speaking the same language, following the same essential traditions. What disappeared was all the high drama, the pomp and the grandeur, the art, the architecture, the priesthood and the pampered nobility. The people had no further need for any of that, and as for the old stone cities? They just walked away, and let the jungle swallow them up.

VISITING TULUM

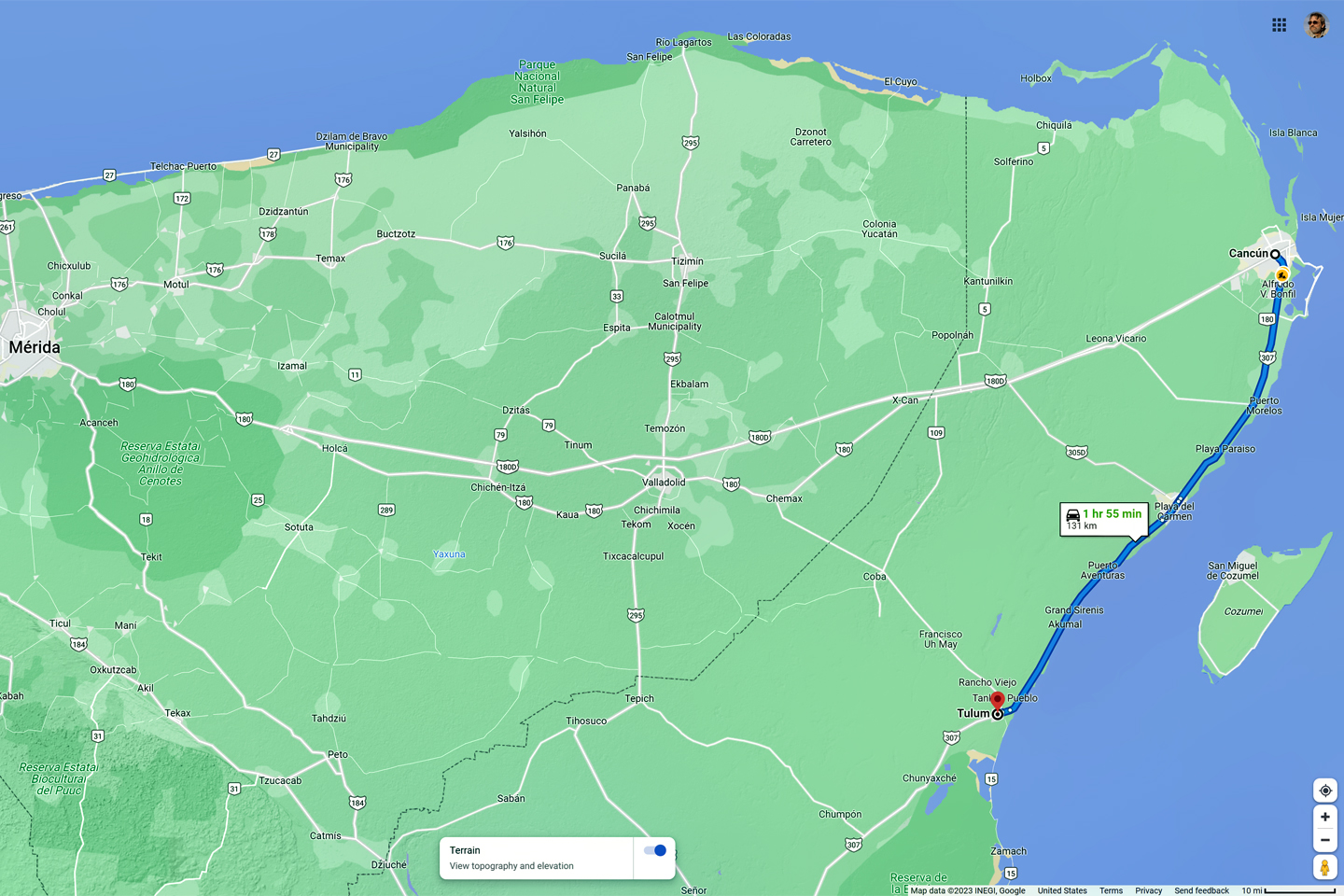

On my most recent trip to Mexico, the quest for Mayan ruins was my top priority. We’d been to Palenque, Uxmal, and Chichen Itza, and even though each of those places was completely different, I was beginning to get a feel for the way things work at Mexico’s archaeological parks. I knew Tulum would be busy, so I wanted to spread my visit across two days, to increase my chances for decent photos. I used the Mexican version of Expedia to book a room ahead of time in the town of Tulum, and we drove down from Cancun, a little less than two hours away on MX 307, a modern highway that parallels the beaches along the Riviera Maya.

We checked into our hotel, had some lunch, then headed to the ruins, which are adjacent to the town. It was mid afternoon, so the park was relatively crowded, despite the fact that we were there in mid-October, the tail end of the rainy season, and one of the least busy times of year in this part of Mexico.

A TIP FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS

If you’re passionate about photography, and if your schedule allows, I highly recommend that you follow my lead: plan to stay the night in Tulum, and spread your visit to the ruins across two days. On your first day, you should look at everything. Use a map to memorize the layout of the ruins, and you should be able to take some decent pictures, despite the crowds, by carefully choosing your angles and using a good zoom lens. The park closes at 5:00, still too early for sunset photos, but the late afternoon light isn’t half bad.

The second day, skip breakfast if you have to, because you’ll want to return to the park at 8:00 AM sharp, just as it opens for the day. Most of the tour groups don’t start arriving until 9:00 or so, which gives you an hour to take your pictures, free of the usual crowds. You’ve already familiarized yourself with the layout, so you’ll know exactly where to go for the best vantage points, and you’ll have terrific early morning light.

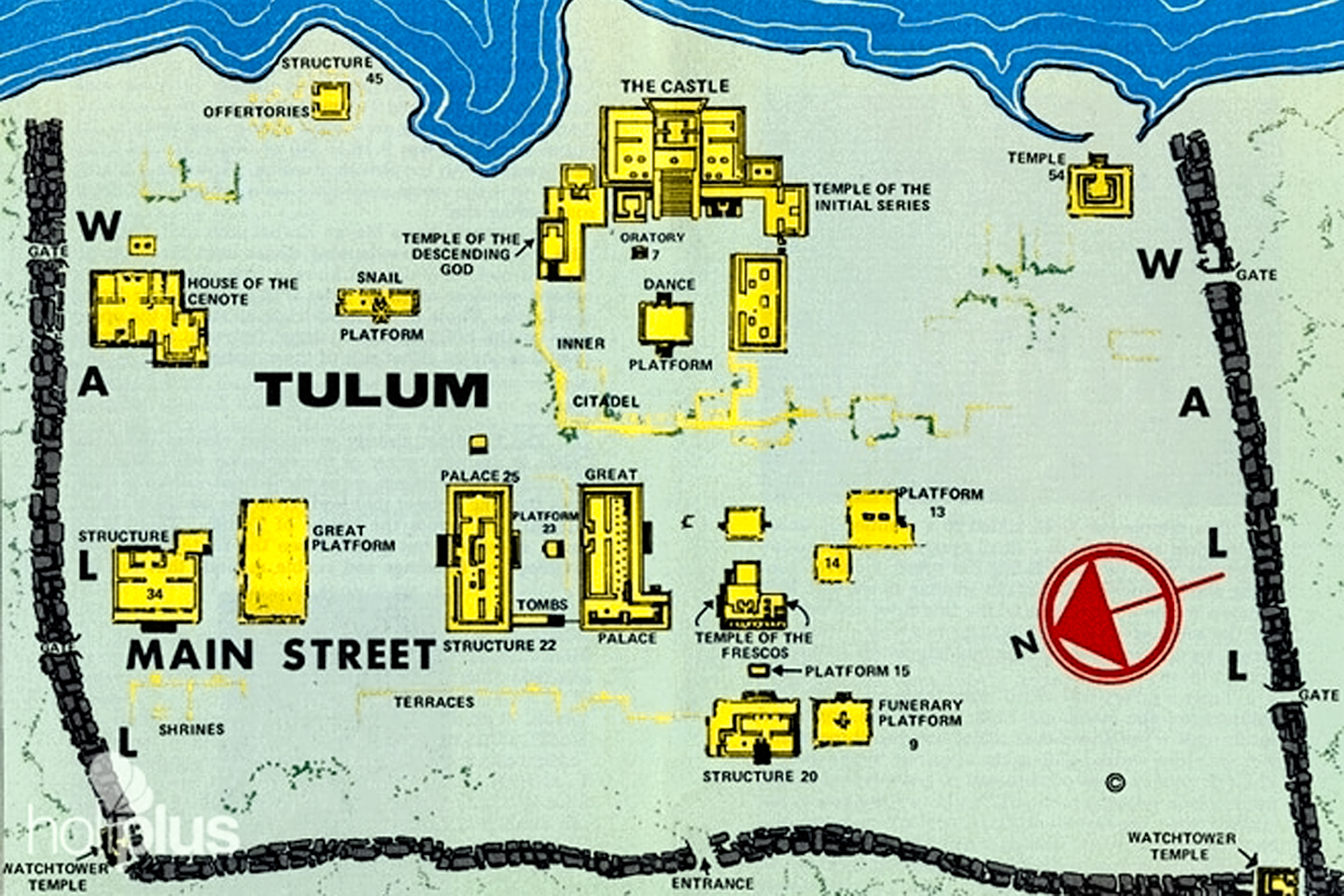

Maps of Tulum and the surrounding area.

Click for an expanded view of all maps and photos

If you join a tour in Cancun or Playa del Carmen, they supply everything, from transportation to tour guide. The down side to that, they set the schedule, and they make all the decisions. If you’re like me, and that’s not your style, it’s simple enough to get to the ruins on your own. The best way is to rent a car, but there are also buses, colectivo taxis (cabs that take multiple passengers for a set fee per person), as well as private taxis, any of which will take you to the town of Tulum from anywhere along the Riviera Maya. The ruins are just 2.5 miles from the town center; close enough to walk, but there are shuttle services available throughout the day.

EXPLORING THE RUINS

Entrance to the Archaeological Park is just 85 Pesos per person, about $4.50 US. If you’ve driven yourself to the site, there is on-site parking that costs an additional 160 Pesos (about $8.00). It’s a half mile hike from the ticket booth to the ruins; if you’d like to save the exertion, a seat on one of the tractor-drawn carts that haul visitors back and forth will set you back another $5 or so. Be sure to bring your own water. There are no concessions, and the only services inside the park are the restrooms.

If you’re not already attached to a tour group, it’s possible to hire a guide at the entrance, either privately, or in the company of a few other visitors. The site is small enough that you won’t really need assistance finding your way around; the benefit of the guide is in their patter, their well-practiced spiel about the history of the ruins, with details about the various buildings, local legends, and the occasional risque anecdote tossed in to spice things up. You’ll have to decide for yourself, whether a guide adds enough value to warrant their fee.

A Mayan arch creates a passageway through the wall that surrounds the ancient city, one of five entry points

THE CASTILLO

The structure best known as the Castillo, the Castle, is a squat truncated pyramid, with a squarish temple on the top and a broad, rather steep staircase climbing the front side. At 25 feet in height, it’s the tallest building in Tulum, the first thing you see when you enter the complex of ruins; an impressive bit of Peten style architecture that dominates the scene.

The Castillo was never used as a residence, so calling it a “Castle” is a bit misleading. The building is thought to have had several functions, and one of the most important was to serve as a landmark, and a lighthouse, readily visible from the sea, as a guide for the trading canoes that plied the coastal waters. It started as a simple shrine at the top of a cliff, but like most Mayan pyramids, new construction enveloped the original building in successive layers, until it evolved into the remarkable monument that you see today.

The Castillo is a Late Post Classic pyramid that’s reminiscent of the buildings at Mayapan and Chichen Itzá, with a very definite Toltec influence. When in use, this combination temple, shrine and lighthouse would have been coated smooth with stucco, painted, and adorned with molded masks and other artwork. The world’s second longest coral reef runs parallel to the east coast of the Yucatan, just under the surface of the sea. It has presented a hazard to shipping since the days of the Maya, but there’s a natural break in the reef, just offshore from the cliffs of Tulum. The sea-facing wall that buttresses the back side of the Castillo was painted bright red, and served as a beacon, guiding boats through the break to the staging area for the port, on the beach below the cliff. The windows in the back wall of the crowning temple would have glowed like a pair of eyes from the signal fires within, for the benefit of boats arriving after dark.

Tulum is the only Mayan city of any size located on a Caribbean beach, which further emphasizes its importance as a port and trading center. Canoes laden with luxury goods came around the Yucatan peninsula from trading centers along the Gulf of Mexico, while others followed the coastline north from as far away as Honduras, possibly even farther. The bright red Castillo, perched atop its cliff, would have been a welcome sight for the weary paddlers in their heavy canoes, a chance to unload and claim their reward, and to rest, before moving on again.

TEMPLE OF THE WIND

After the Castillo, the next most famous structure at Tulum is a relatively small building known as the Temple of the Wind. It’s not the least bit impressive from an architectural standpoint: a square shrine, with a cement roof and a single door, built atop small stone platform . What makes this one special is location, location, and location! Perched on a rocky outcropping that juts out into the sea, this is another structure that’s visible from the water for a considerable distance. Perfectly situated to catch the offshore breeze, it’s an ideal spot to put a shrine dedicated to the wind god.

Three views of the Temple of the Wind, a Mayan shrine on the azure shores of the Caribbean Sea

THE PALACE (HOUSE OF THE COLUMNS)

There are several large buildings in the plaza at the foot of the Castillo. The Palacio, the Palace, sometimes referred to as the House of the Columns, was a four room structure that was used as a residence by the city’s elite. Numerous columns supported the beam and mortar roof, which long since deteriorated to the point of collapse. Some of the original stucco with traces of red pigment can still be seen on the wall at the rear of the building.

The Palace, also known as the House of the Columns

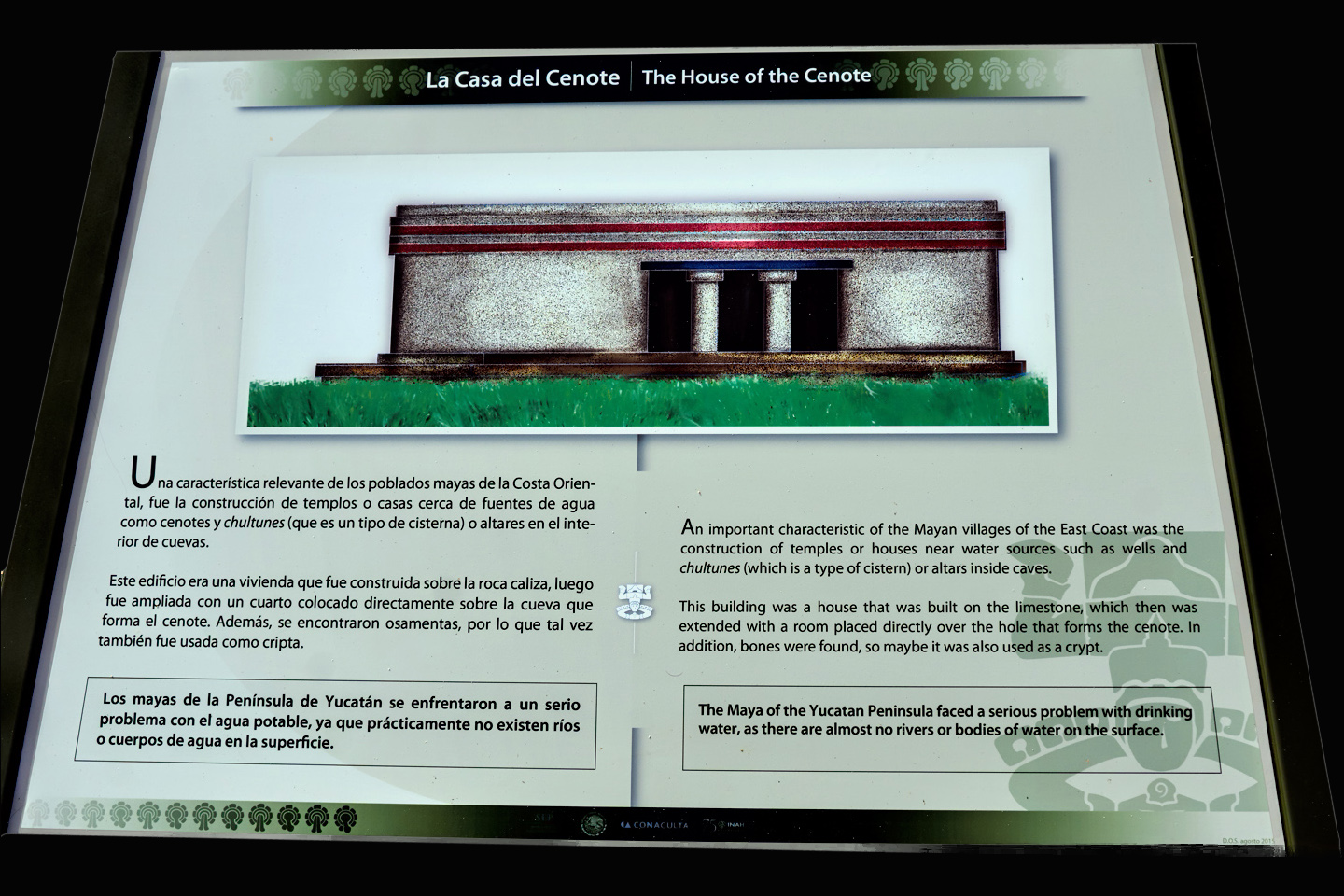

HOUSE OF THE CENOTE

Cenotes are natural sinkholes in the limestone bedrock of the Yucatan, and they’re an important source of fresh water in a region without lakes or streams above ground. This building was probably a temple of some sort, and at least one burial was located inside it. A new section was added to the original structure, directly above the roof of a water-filled cave. A hole dug through the floor provides access to the water. It’s not a natural cenote, but it clearly served the same purpose.

Two views of the House of the Cenote

Several views of the Temple of the Frescoes. Traces of red paint are still visible on the outside walls of the upper story. Note the cell phone tower in the upper left corner of the wide shot. That’s Progress: now you can post to Instagram instantly.

TEMPLE OF THE FRESCOES

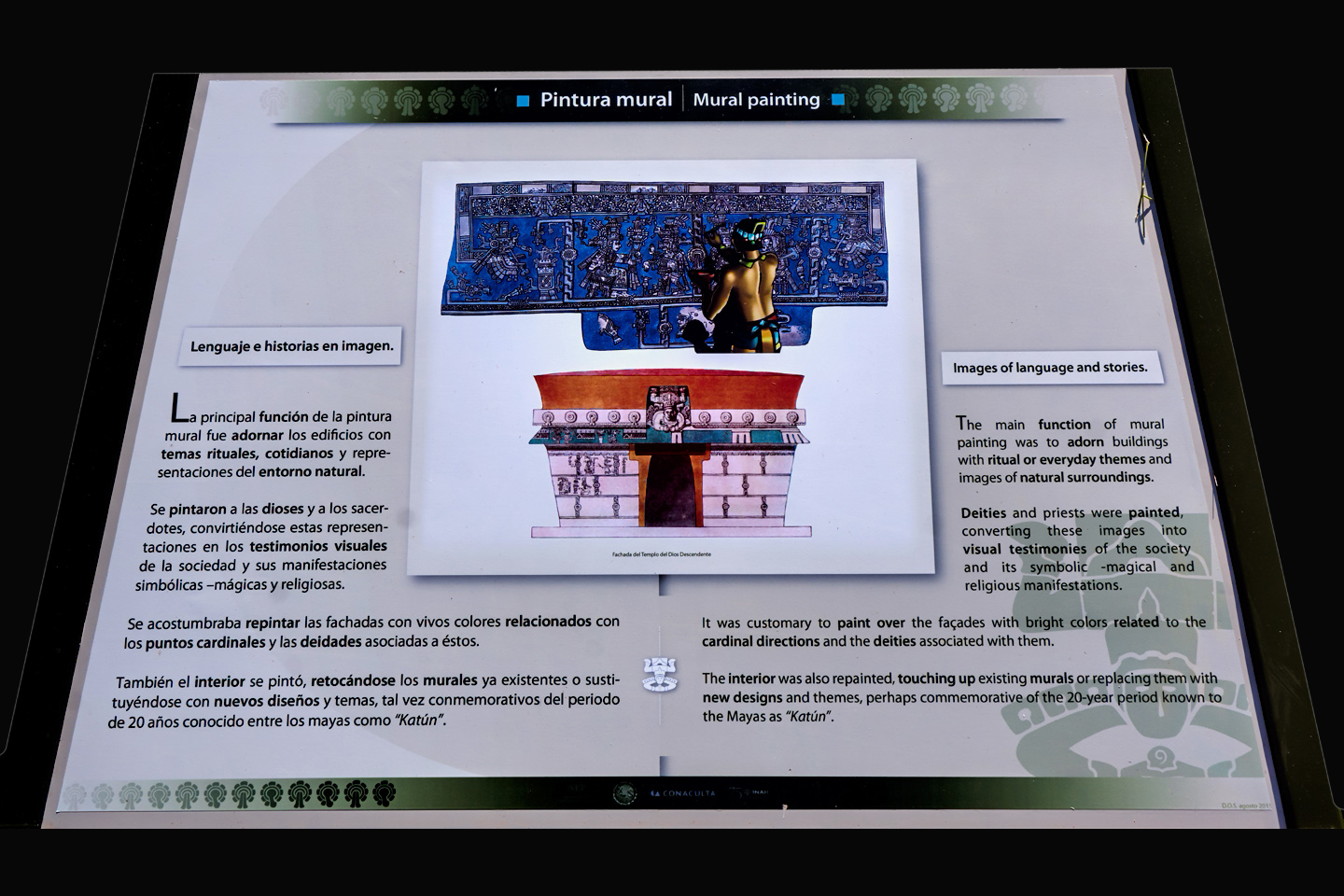

Another impressive structure is the two story building known as the Temple of the Frescoes, named for the painted murals that once covered the interior walls. The murals have deteriorated significantly over the years, so visitors are no longer allowed inside the structure to view them. The moisture in our breath, especially when concentrated in a confined space, causes irreversible damage to these rare and precious paintings. Brightly colored murals once graced nearly every interior wall in the Mayan cities, but few have survived the ravages of time.

THE HOUSE OF THE HALACH UINIC

The ruler of Tulum was known as the Halach Uinic, a hereditary position passed on to the eldest son of the family. The ruler appointed all the administrators, and with their support he had absolute power over the community. The position came with an official residence, the House of the Halach Uinic, a massive structure that is still in remarkably good condition.

Above the doorway is a figure made from molded stucco, an image of the Descending, or Diving God, a winged deity that is always portrayed upside down, as if falling from the sky, with his arms pointed downward and his legs in the air. The Descending God had some special significance in Tulum, as it is a motif that is repeated on several of the important buildings.

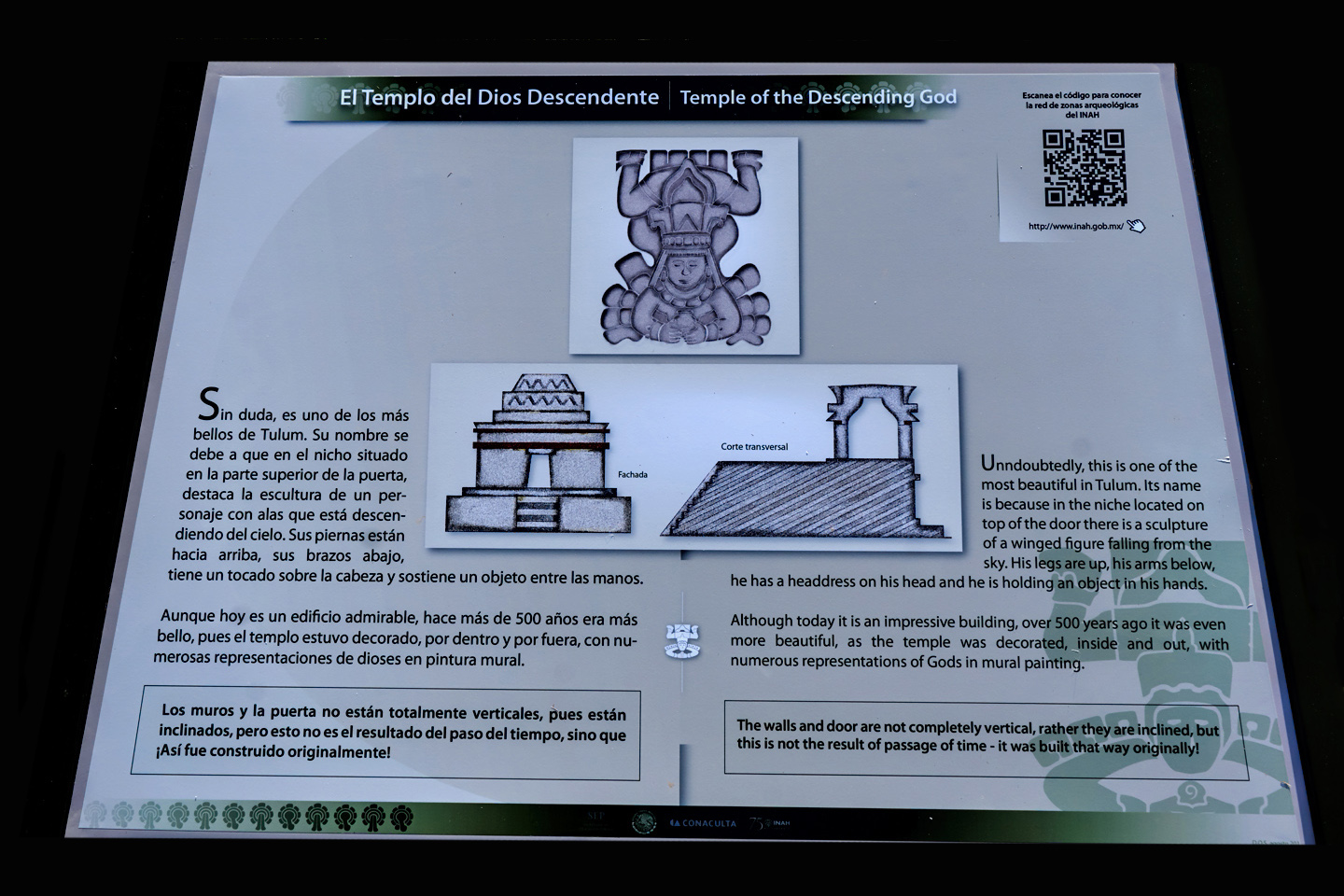

TEMPLE OF THE DESCENDING GOD

This small, rather elegant temple stands beside the Castillo, and is named for the molded figure of the Descending God that’s prominently featured in a niche above the door. There is a painted mural inside the building, but, just like at the Temple of the Frescoes, entry is prohibited, in order to protect the paintings from the moisture in visitor’s breath.

The Descending God is thought to be associated with the planet Venus, as well as with Ah Muu Zen Caab, the Mayan God of the Bees. Honey produced by bees was a mainstay of the trade that supported the noble houses of Tulum; it was used throughout the Yucatan as a sweetener, an antibiotic, and in a fermented drink called balché, similar to mead. Images of the odd god with his legs in the air are also found in the Mayan cities of Coba, Sayil, and Chichen Itzá, three of Tulum’s most important trading partners. The Mayan Cities were independent entities, but there were many connections between them that we’re only just beginning to understand.

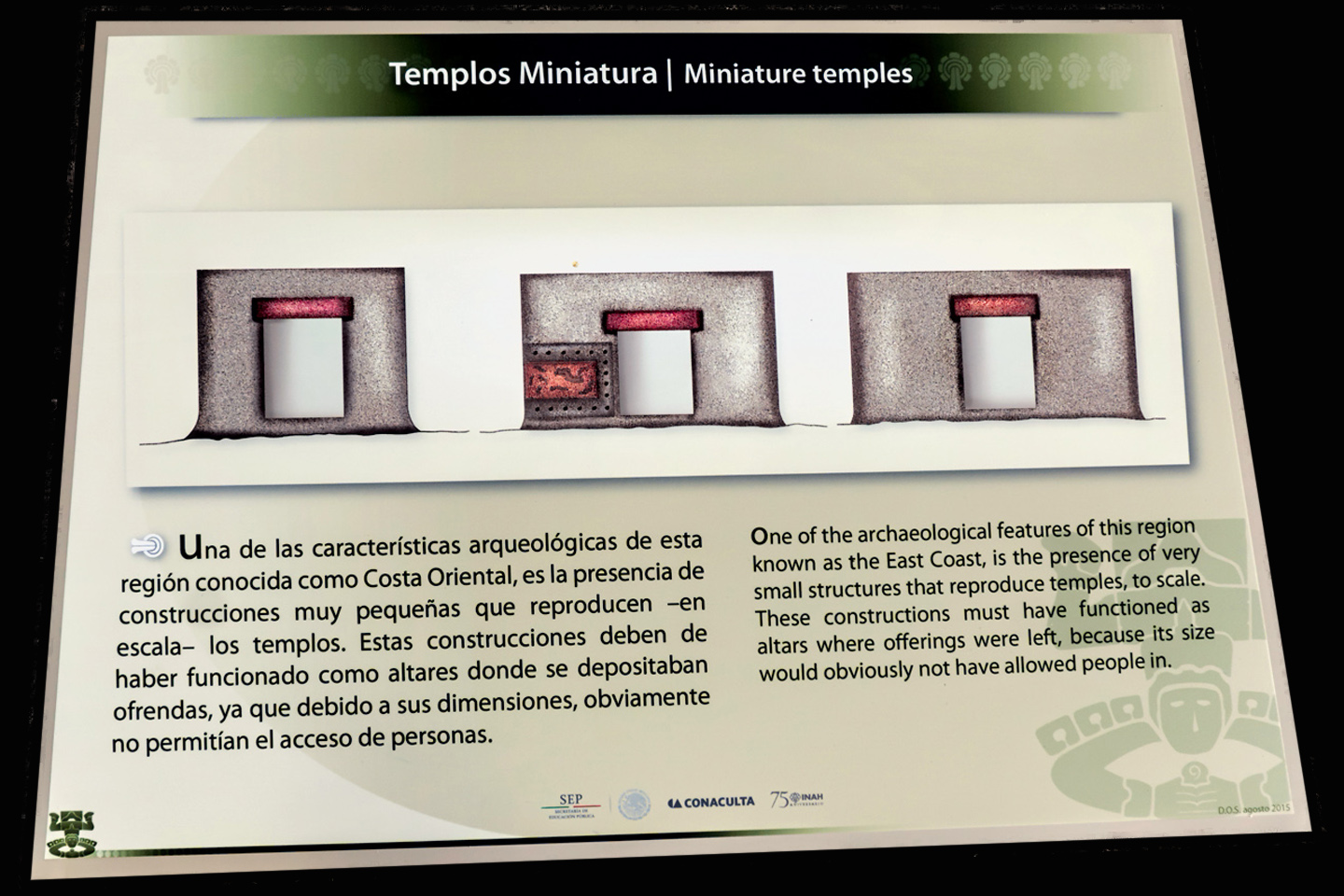

TINY TEMPLES

At several different locations, in Tulum, as well as in other Mayan communities along the east coast of the Yucatan, there are small structures that are like scale models of temples, complete with doorways and interior spaces. It’s assumed that these were used as repositories for offerings.

THE BOUNDARY WALL

Tulum was protected by cliffs on the eastern, seaward side, and by a wall that surrounded the other three sides of the twenty acre ceremonial enclave. The wall is thought to have served a dual purpose. It was there to keep out invaders, and it was also a physical boundary between the elite priests and nobels and the common people. The massive barrier was a monumental construction in it’s own right. Built entirely of stone, it ranged from 10 to 16 feet in height, and it was as much as 26 feet thick, following the contours of the land for a total distance of 1300 feet, with the longest section, on the western side, running parallel to the sea.

There are five openings in the wall, two on the north end, two on the south, and one in the center of the western side, which is currently used as an entrance for visitors. Some sections of the wall are hollow, with stairs on the inside leading up to the top. At each of the rear corners, there are structures believed to have been watch towers, vantage points for the guards that were needed to keep the city safe from attack by land, as well as by sea.

THE ELITE ENCLAVE, INSIDE THE WALL

Most of the residents of Tulum lived outside the wall in simple dwellings built of wood and thatch, materials that have not survived the passage of time. There are archaeological remains, plenty of stuff still buried for the scientists to sift through, but there’s nothing above ground for the rest of us to see, because the monumental construction was confined to the area inside the wall.

The priests, the nobels, and the rising class of wealthy merchants lived a very good life here. Through their observations of the stars and planets, they knew the cycle of the seasons, when to plant and when to harvest, and with the wealth they acquired through trade, they had absolute control over everything that happened in their corner of the world. The common people were there to serve them, to see to their every need, and their trade relationships with the powerful lords of the inland cities kept them safe from other agressors. It was a true golden age, but it wasn’t destined to last.

SIGNS

The Mexican government’s Council for Culture and the Arts (Conaculta) has provided illustrated signage in both Spanish and English at various locations around the ruins. Some of them identify the buildings, while others provide interesting information about Mayan history and culture. Click the thumbnails to expand the images:

Witness of the Dawn: A Cultural Decline; and Mercantile Corridor: The East Coast

Trade and Navigation viewpoint

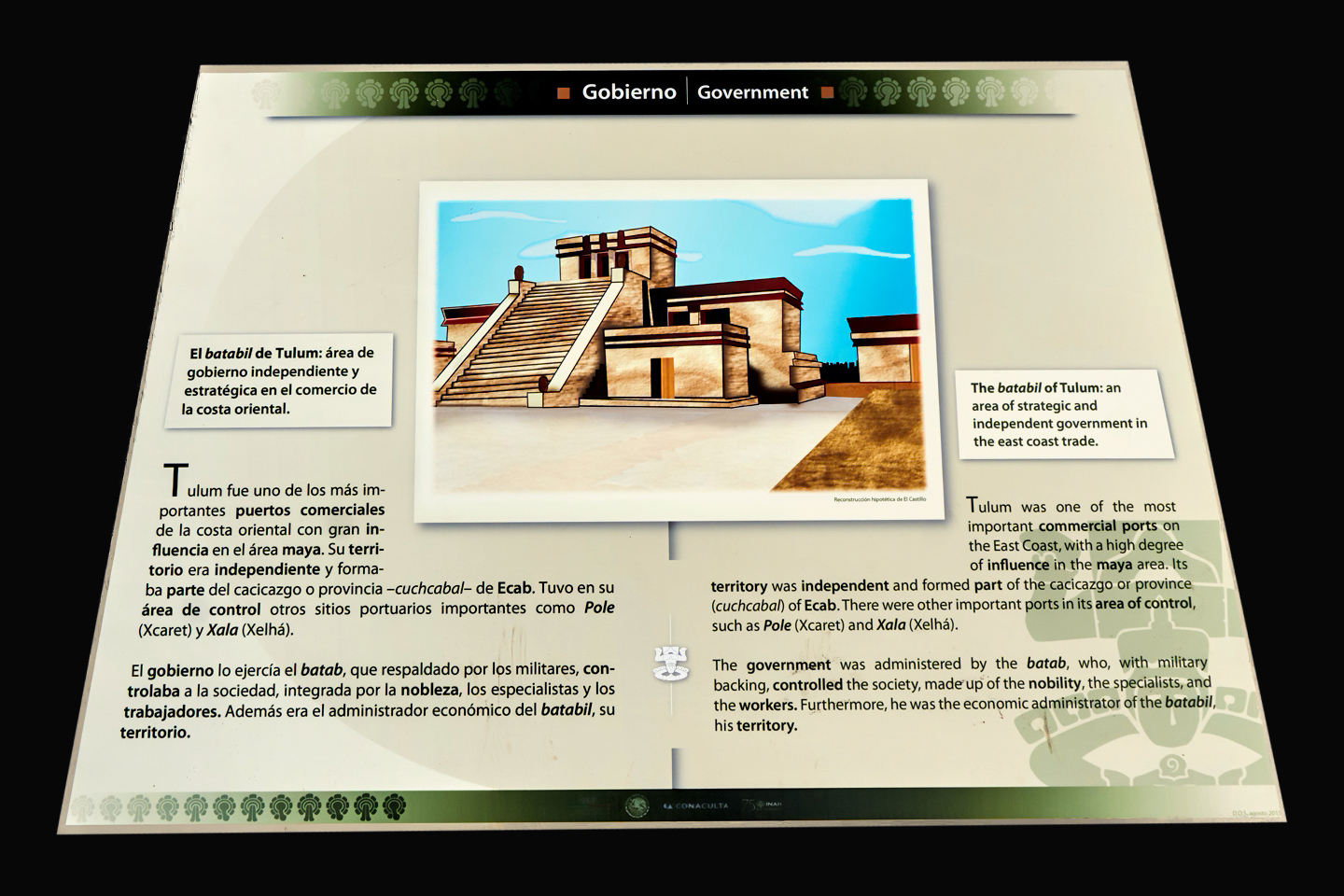

Government

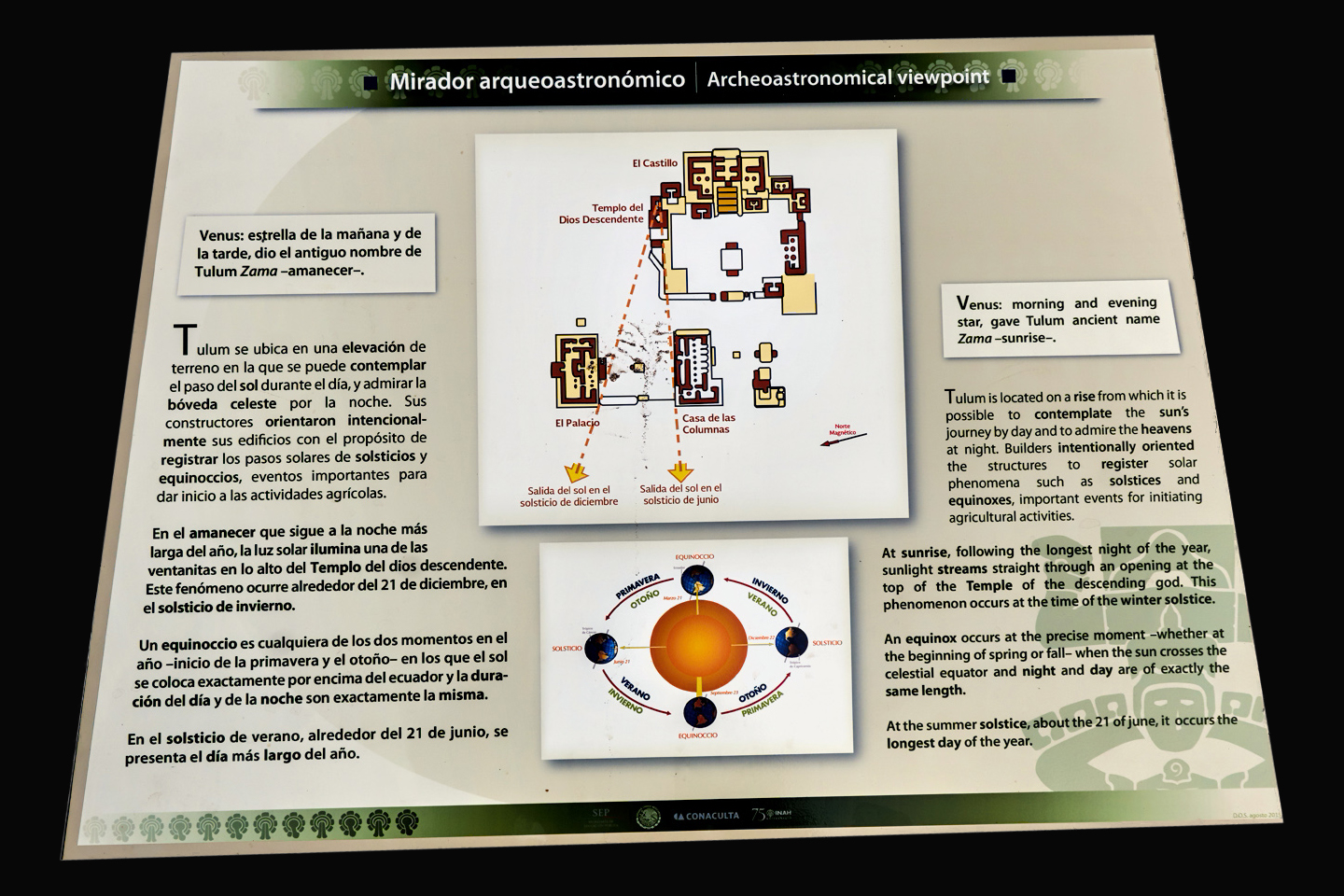

Archeoastronomical Viewpoint

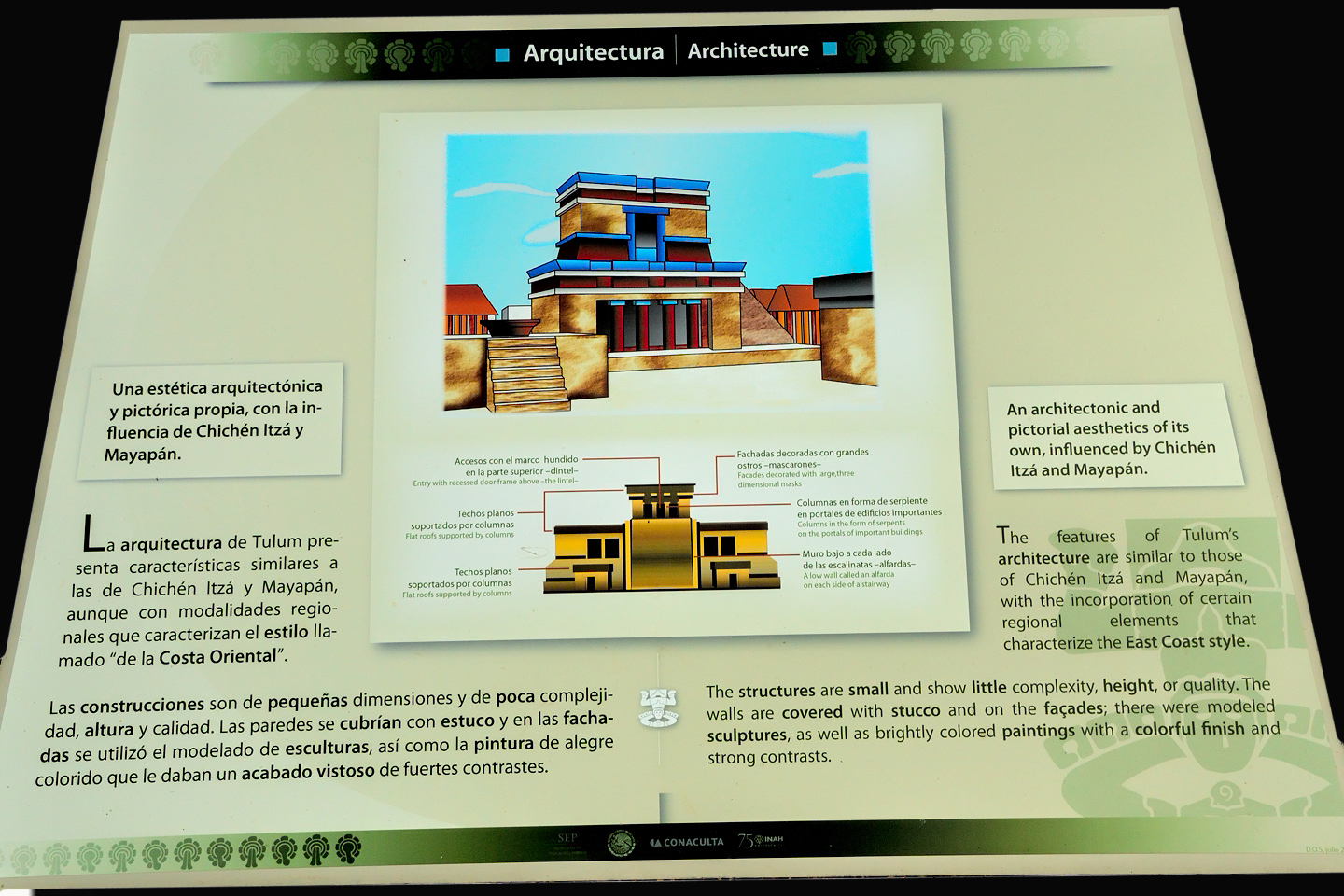

Architecture

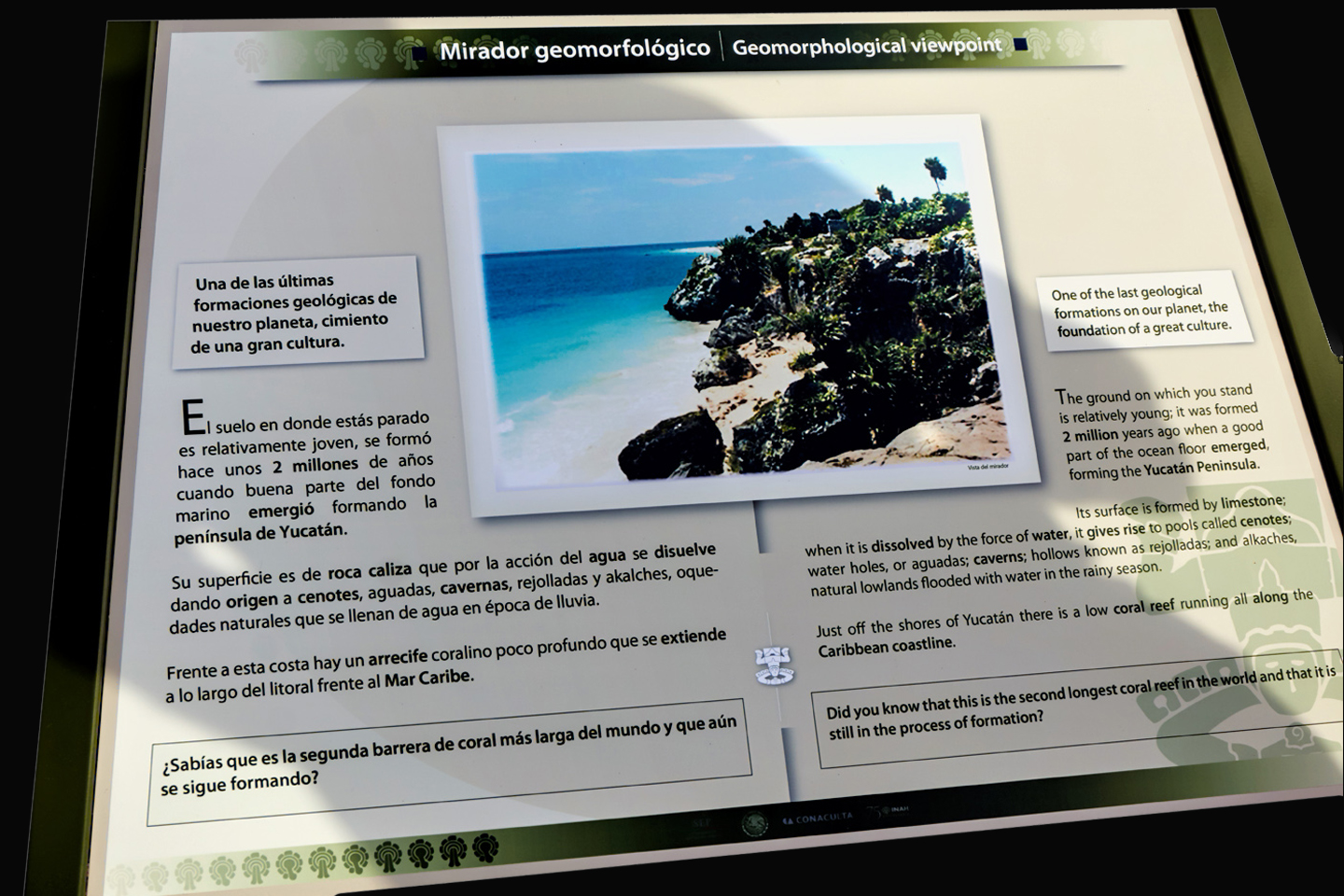

Geomorphological Viewpoint

Mural Painting

CURRENT RESIDENTS

Assorted Spiny Tailed Iguanas among the ruins, and an Agouti in the Underbrush

Every Mayan ruin that we stopped at, from the crowded sites like Chichen Itzá and Tulum to the less visited sites like Edzná, they all had one thing in common: they’re crawling with Iguanas! Mexican Spiny Tailed Iguanas, Black Spiny Tailed Iguanas, and Yucatan Spiny Tailed Iguanas, just to name a few. When the Mayans moved out, the Iguanas moved in, and they’ve made themselves very much at home among the ruins.

I’ve never been a bird watcher, but I am a bird lover, and I’ve always enjoyed taking pictures of them, even when I don’t have a clue as to the species. After-the-fact identification has never been easier: drag and drop just about any bird photo into the Google search bar, and nine times out of ten, you’ll get a hit. In this case, it took the search engine all of half a second to identify the bright blue bird with the yellow beak as a Yucatan Jay. The brown bird in the middle of his meal is a Great Tailed Grackle, and the pair of high flyers silhuetted against the clouds are Frigate Birds. Pretty cool!

Tulum is a fantastic place to visit, in spite of the usual crowds. We can only imagine what it would have been like when it was still in use, with all the sights, sounds, and smells of a living city teeming with people, with the kings and nobles in their palaces, and the priests in their temples. What a different world that was, and not so very long ago.

Click the link to launch a Full Screen slide show featuring an assortment of my favorite photos from Tulum. These super-sized slides are best viewed on a full sized monitor or a tablet. They’re not properly configured for a Mobile browser.

Note: This is a revised and expanded version of a previous post that was titled: Tulum: The Mayan City by the Sea

Unless otherwise noted, all of these photographs are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

READ MORE LIKE THIS:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I've ever seen. There's a powerful energy in that spot--maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps--but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I've ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I've ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Photographer's Assignment: Chichen Itza

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Coba and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Coba was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Becan and Chicanna: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

Mexican Road Trip: How to Plan and Prepare for a Drive to the Yucatan

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancun, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancun from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

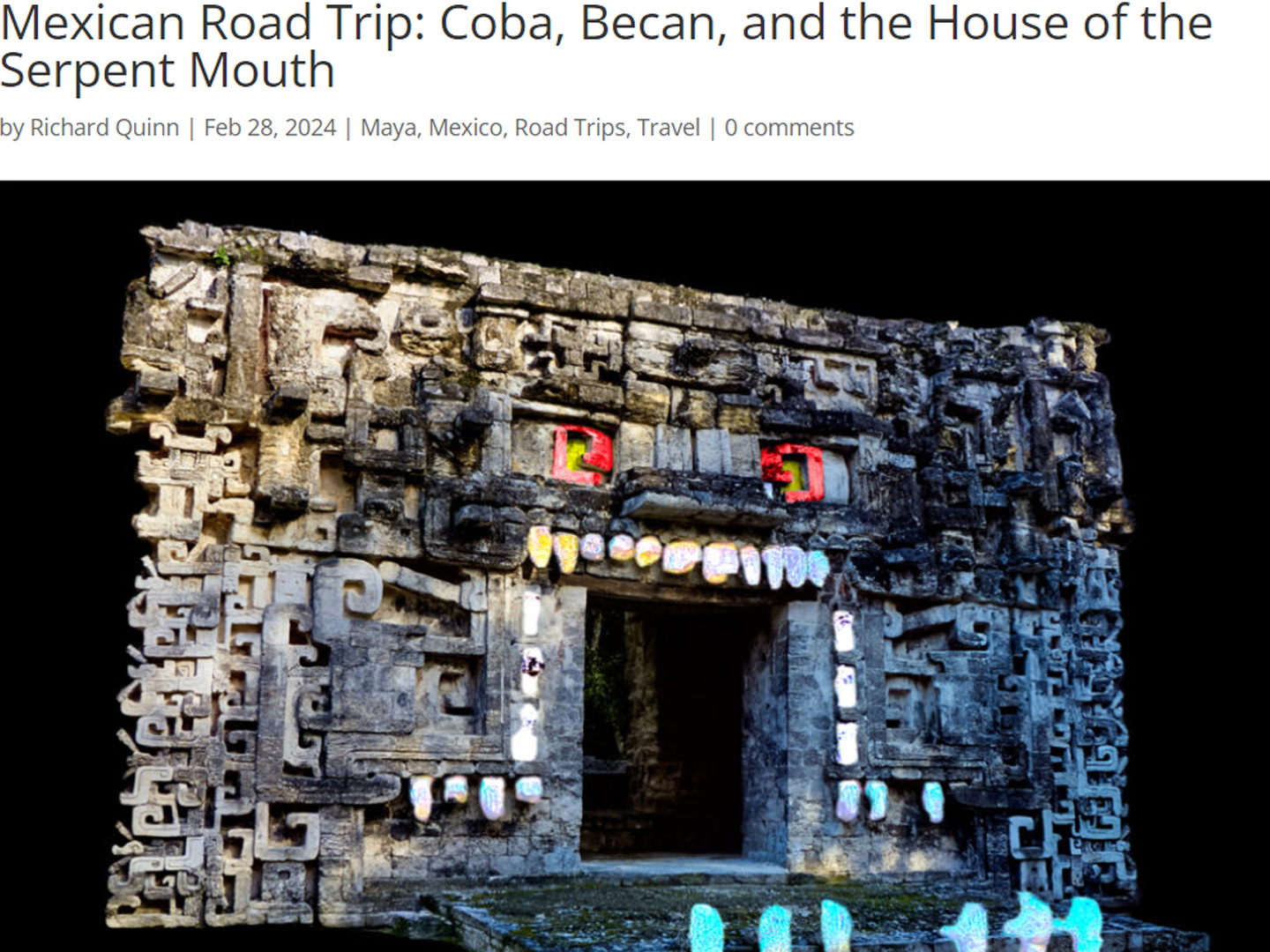

Mexican Road Trip: Coba, Becan, and the House of the Serpent Mouth

After Tulum, we drove south, then west, headed back to Campeche. Along the way, we visited some Mayan ruins that are less well known, starting with Coba. the major Mayan city northwest of Tulum, followed by Muyil, Becan, and Chicanna. Each site was unique, and each of them added another piece to the puzzle of the ancient Maya.

(This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication: March 2024)

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

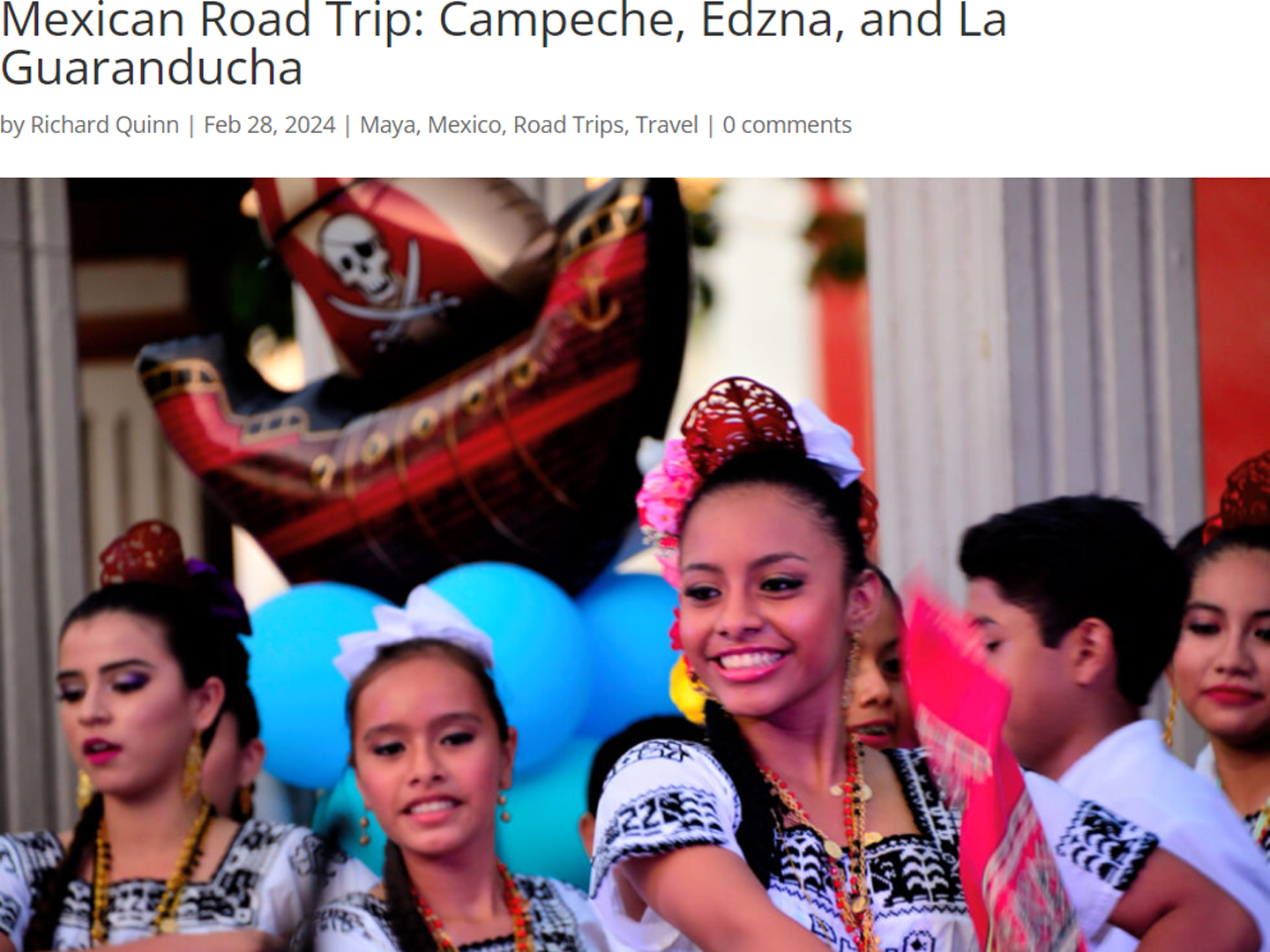

Mexican Road Trip: Campeche, Edzna, and La Guaranducha

(This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication: April 2024)

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico's Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they've adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It's a wonderful, colorful parade that's all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

A shout out to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. "Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins" was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after "Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali." We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Road trips with old friends are the absolute best. We laugh and we laugh until we run out of breath, and laughter is good for the soul!

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Hope to god somebody pays you to use any part of this for their tourist ads.